“An old thing becomes new if you detach it from what usually surrounds it.” -Robert Bresson

Authenticity is a difficult quality to pin down. It’s a sort of patina on the surface of a thing- a texture that is in constant danger of wearing away on each new examination. In art, the authenticity of a work is rarely connected to its fidelity, but rather to a total synchronicity of parts, an internal consistency. There’s a part of our perceptual process that is always evaluating this, and it’s usually better at its job than that conscious, creative faculty we use to make representative art.

After decades of CG in film, filmmakers gradually lost the ability to make an audience think of an image as being ‘real’ (if that was ever even the intention), and at best hope only to stun them with visual complexity. It’s now a marketing point when a movie can claim expensive and complex practical effects instead of CG, not necessarily because the audience can recognize the difference, but because by believing in the reality of an image, they feel re-engaged with what they see on screen.

Even with the present lip service towards ‘real’ sets and practical effects, we have always expected a high level of artifice in the genre of science fiction. Prior to computer generated imagery in movies, matte glass painting, models, full-size sets and in-camera animation techniques achieved much of the same effects, albeit more rigidly.

One of the strengths of filmmaking as a medium is its ability to simply capture the world around us in-place and recontextualize those images. There’s been lots of movements in film that have used direct, observational methods to try to lay claim on authenticity, but here I’m going to talk about something different- films that use a high level of editorial and expositional artifice to make ‘real’ footage represent something fantastic, while retaining that inherent patina of authenticity. Using a ‘grown’ world as opposed to one meticulously built by the artist breaks the ‘black box’ ( as Walter Murch terms it 1. ) It cedes some control away from the artist and reintroduces complexity that can’t be otherwise fabricated.

Here are a handful of films that claim their place in the science fiction cannon simply by showing the world around us in a new light.

Science and technology as a negative force run amok is a common theme in genre fiction. The optimistic view of technology as a means to a utopia that was common in pulp and television science fiction in the 50’s and 60’s has felt out of place in the public imagination for a long time. Artist Patricia Piccinini has her own take on the Faustian scientist trope -

“To my mind the fatal flaw that condemns Doctor Frankenstein in Mary Shelly’s story is not hubris. It is not that he has sought to, or even succeeded, creating life from nothing but his own desire and reason. Frankenstein’s mistake is that having done this he does not take responsibility for his creation. Having brought this creature into the world, he should also be liable for its life here. He was not a good parent. 2”

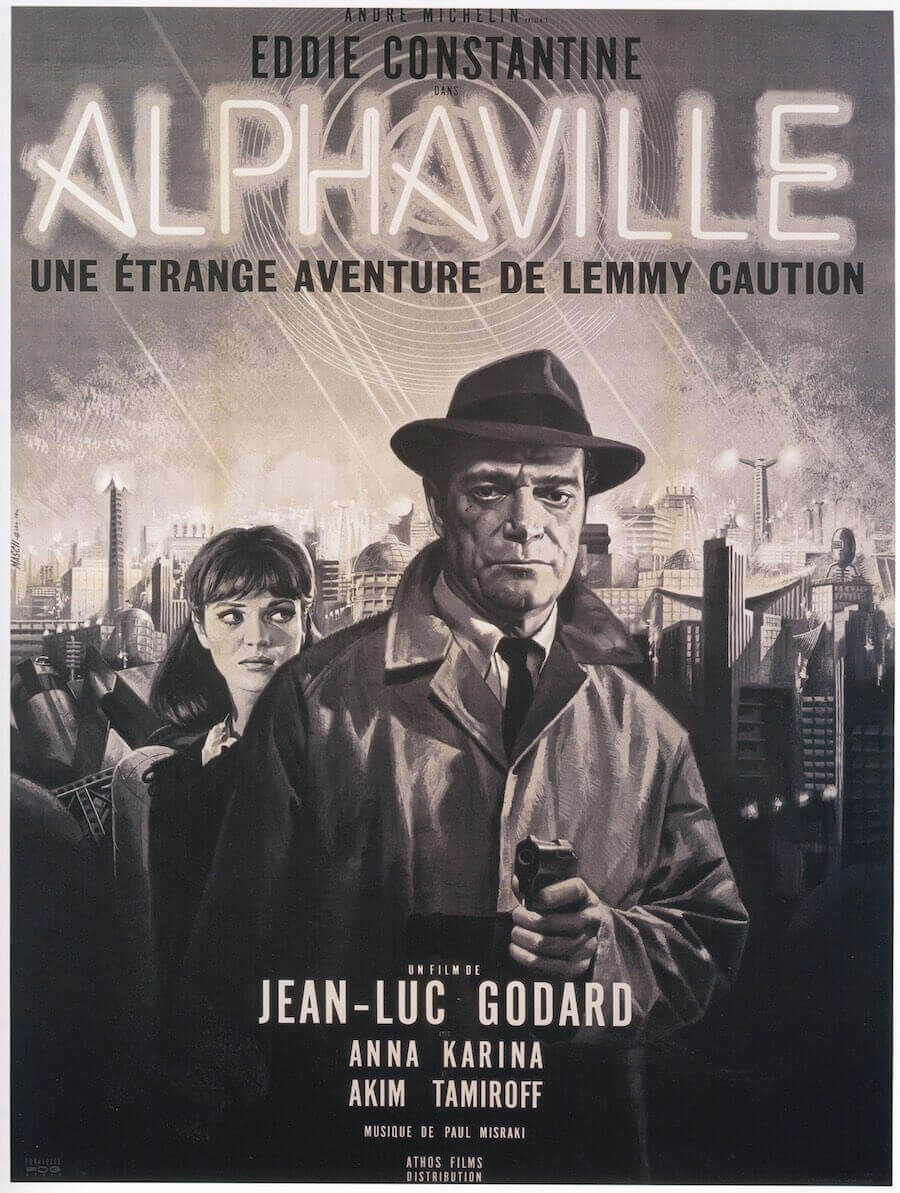

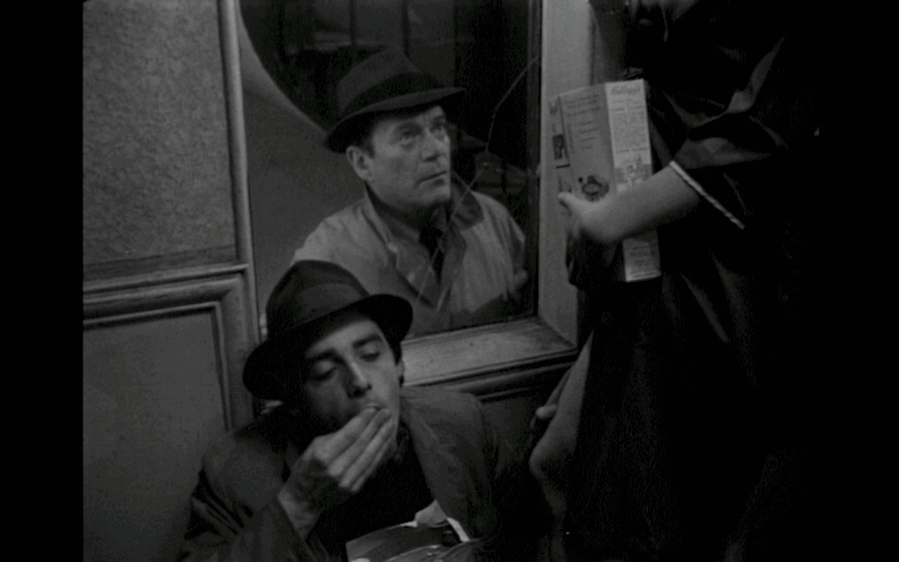

In Alphaville (1965), Jean Luc Godard shows science as a bloodless force for dehumanization, led not by scientists themselves, but by a nonhuman machine-intelligence (with a voice lent by a throat cancer survivor using an assistive device). The Alpha-60 computer has a goal of a rigid hive-society, free of the stickier emotions of mainstream humanity. The hero here is the stony faced detective “Lemmy Caution” (a character lifted completely, American expatriate actor and all, from an established noir detective series). Lemmy shoots, punches, and photographs his way through the city of Alphaville, on a mission to find (and kill) the scientist creator of the Alpha-60, “Professor Von Braun” (evoking Werner Von Braun, creator of the V2 rocket who worked for both the Third Reich and later the United States).

“Everything weird is normal in this city of whores.” - Alphaville

Photographed in stark black and white, saturated with pitiless, obscuring shadows, and punctuated by absurdly sinister orchestra hits and random violence, Godard’s roaming camera shows Paris through the contrasting lenses of both noir and SF, a stylistic mix we would eventually see echoed in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner. Godard amplifies each style to the extreme, until the film becomes a farce of genre conventions. Futuristic architecture in the film are on-location shots of the Hotel Sofitel Paris le Scribe and the Paris Electricity Board Building. Much of the content of the film was improvised, and Godard reportedly funded the film with money from German investors by sending them a phony Lemmy Caution script that was never shot.

In our current world science is both championed for commercial gain and decried by the same voices in nearly the same breath as they see fit. Big business decides what research has value, and to what ends technology is used, not the scientists that conceive it. In a way Godard’s vision of technocrats enslaved by their own creation may not be so outrageous.

“Nothing sorts memories from ordinary moments. They claim remembrance when they show their scars.” - La Jette

La Jette (1962) implies another degraded world, one so thoroughly ruined that it cannot even be shown beyond a few darkened underground hovels and stock photos of devastated ruins from World War II. In photo montage form, Filmmaker Chris Marker shows us his character’s flight back in time from this uninhabitable future into the present. Eventually the protagonist becomes so mesmerized by the world we take for granted that he is lead to his own death, an inevitable event that he had already witnessed in his childhood as an onlooker. In La Jette the strange becomes familiar, the future becomes the present, the inevitable thing we fear most must come to pass, and has already defined us by its inevitability. This is a personal and philosophical film, and its use of the present day shown as new through the eyes of a time traveller is perhaps the most immediate and visceral of any science fiction film. It was later used as the basis for Terry Gilliam’s film 12 Monkeys.

“We look at the present through a rear-view mirror. We march backwards into the future.” - Marshall MCLuhan

La Jette’s creator Chris Marker was an extremely private figure, working pseudonymously throughout his career. He was considerably older than Godard, having fought as a young man in the French Resistance during World War II and later joining the French Communist party. He was a prolific artist, and La Jetee is sometimes credited with establishing the form of film-essay. By subverting documentary conventions, the film essay can construct a wide range of narratives- fictional, personal, polemical, surreal.

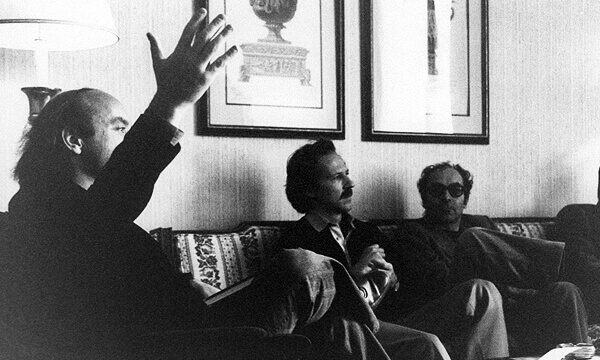

One of the greatest innovators of the film essay form is Austrian-born director Werner Herzog. Herzog is widely quoted as dismissing Godard, “Someone like Jean-Luc Godard is for me intellectual counterfeit money when compared to a good kung-fu film.” The two were once photographed together in 1980, meeting famed Japanese director Akira Kurosawa. Herzog is engaged in conversation with Kurosawa, and reportedly altered his travel plans to return the next day to deliver a book of illustrations to him. Godard is silent throughout the encounter and looks on with a bemused and distracted expression. I haven’t found records of any other interactions between the two, but Herzog is famously contemptuous of film theorizing, and was unpopular with the late 60’s Euopean left, as his film Even Dwarfs Started Small was considered by some as a lampooning of the ‘68 student riots that had swept France, coinciding with protests in other countries. Herzog dismissed political readings of his own work. He also has consistently relished tearing down assumptions of truth in Cinema Verité and documentary filmmaking. In his Minnesota Declaration he states, “By dint of declaration the so-called Cinema Verité is devoid of verité. It reaches a merely superficial truth, the truth of accountants.”

“I am a storyteller, and I used the voice-over to place the film – and the audience – in a darkened planet somewhere in our solar system.”

In Lessons of Darkness (1997), Werner Herzog reveals an emotionally and politically charged scene, the Kuwaiti oil fires and debased victims left in the wake of the first Gulf War. However, he creates something very different from a standard documentary in his depiction of the scene. Herzog elects to present it as the unfathomable, hellish panorama of an alien world. Landscapes of oil, smoke, fire, and blackened earth are shown with the same kind of awestruck revelation that is usually only afforded to multi-million dollar effects shots. The difference here being that this alien world is incalculably more “real”.

“I think science fiction films are wonderful because they are pure imagination and that is what cinema is about, but on the other hand, all of these films hint that what you see is artificially made in a studio with digital effects. This is the issue of truthfulness in today’s cinema. It’s not about realism or naturalism, I’m speaking of something different. Nowdays even six-year-olds know when something is a special effect and even how the shot is done 3.”

“Calling Lessons of Darkness a science fiction film is a way of explaining that the film has not a single frame that can be recognized as our planet, and yet we know it must have been shot here” relates the director, “ I am a storyteller, and I used the voice-over to place the film – and the audience – in a darkened planet somewhere in our solar system 4.”

Lessons of Darkness is the first of two of Herzog’s films to place what might have otherwise been considered documentary footage in a science fiction context. The Wild Blue Yonder uses NASA footage of working astronauts and scenes of Antarctic divers to create a story about alien visitors, narrated by a wild-eyed Brad Dourif. Dourif’s performance has the added effect of creating another layer of interpretation, where the whole story could be the ramblings of a mentally ill human with delusions of grandeur. Lessons of Darkness is texturally a very different film from The Wild Blue Yonder and reactions to the two were very different. The Wild Blue Yonder was uncontroversial, but Lessons of Darkness polarized audiences, winning Grand Prix at the Melbourne Film Festival while causing an outcry at the Berlin Film Festival. Critics accused Herzog of aestheticising the horrors of war while divorcing it from its political context. Herzog has argued that this handling of the footage gave it deeper and more disturbing impact rather than fetishizing it.

“…we have all watched so many horrific things on the news that we have become totally – and dangerously – inured to them… The stylization of the horror in Lessons of Darkness means that the images penetrate deeper than the CNN footage ever could.”

Based on Boris and Arkady Strugatsy’s novel Roadside Picnic, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979) persuades us that the empty, overgrown areas around chemical facories and powerplants in Estonia are the no-man’s land surrounding a forbidden room where some cosmic collision once occurred. A year of footage from shooting in these toxic landscapes had to be discarded after the film was improperly developed by Soviet labs, and Tarkovsky essentially began the film again from scratch with a new director of photography. Several crew members, including Tarkovksy himself, died of cancers or illnesses that may have been attributable to the long periods of time spent working in these locations.

Stalker, dream sequence excerpt

Much has been written about the parallels between Stalker’s “zone” and the “alienation zone” surrounding the center of the Chernobyl nuclear accident, the landscape of the latter coupled with the themes of the former became the subject of an unlikely and imaginative videogame S.T.A.L.K.E.R.

The British Film Institute has posted a piece with accompanying film stills about the content and production of Tarkovsky’s two science-fiction films, Stalker and Solaris. Both films are highly introspective and meditative, and did nothing to help Tarkovsky’s already difficult standing with Soviet censors, who already considered him a decadent spiritualist. They also contain some of his most enduring images. Stalker is a movie of textures- rust, foliage, dirt, flowing water, foam and flotsam. While the composition of every shot in the film is as precisely arranged as the gears in a stopwatch, the textures must all be real, and the assemblage of the fiction becomes tangible by their authenticity.

After Tarkovsky’s death in exile from lung cancer, Chris Marker made a film essay in homage to the great director.

One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich

Letterboxd collection- The Distant Future of the Here and Now

also: Geoff Dyer, Paul Farley and Werner Herzog discuss Geoff Dyer’s book inspired by Stalker

Guillaume, Guillaume, Guillaume, the cat named Guillaume by Everest Pipkin