(Originally published on the World of Mondo blog)

Carl Barks, the artist who created Scrooge McDuck, started work at Disney in 1935 as an inbetweener, drawing innumerable piles of Disney animation frames for 20 dollars a week 1. Inbetweening is the most grueling and thankless of jobs in animation (we now farm these jobs out to Asia to be done by children wearing rags who are lorded over by shirtless dudes with bullwhips and executioner’s masks). While Barks was working as an inbetweener, he regularly submitted ideas for cartoons in development to keep from losing his mind in the brutal tedium of his work. His first joke to be accepted by Disney involved the already established character Donald Duck having his ass shaved by a robot barber (Already the sparkle of his innate genius had begun to shine through). Barks finally quit in disgust to try and start a chicken farm in the inhospitable Inland Empire area of Los Angeles, but not before contributing artwork for the first Donald Duck themed comic strip. While his chicken farm floundered and failed, Barks was forced to go back to Western Publishing, the company that had put out the licensed Donald Duck comic that he had worked on, and ask for extra work. Smelling bird on him, they put him back on Donald Duck. Barks produced an estimated 500 books for Western Publishing involving ducks, and in the process, took one apoplectic, two-dimensional duck, and invented an entire universe around him- a universe that sometimes barely needed or noticed the character that it had sprung from.

This image is far from a complete family tree, for a terrifyingly exhaustive one, click here. For an online history of Duckburg, click here.

This image is far from a complete family tree, for a terrifyingly exhaustive one, click here. For an online history of Duckburg, click here.

Disney works hard to present a monolithic face, and none of Barks’ comics carried his name, only “Walt Disney Presents”. However, because his work was uniquely imagined and had a un-homogenized style to it that was unduplicated anywhere else in Disney’s output, people started to notice, and referred to him as “The Good Duck artist”. The Good Duck artist lived to the age of 99, occasionally taking time to do oil paintings of ducks, to be snapped up by rabid fans for thousands of dollars. Interestingly, the story of Duckburg doesn’t stop there. In fact, like most good acts of focused and slightly unhinged creativity, Barks’ work radiates out through culture, setting off bizarre chain reactions. For a small example, Lucas and Speilberg have publicly acknowledged that the rolling boulder intro to “RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK” (1981) was inspired by Uncle Scrooge Comics 2 ( “The Seven Cities of Cibola” From Walt Disney’s Uncle Scrooge #7, September 1954). And then there’s the odd effect that Scrooge McDuck comics had when left behind by G.I.’s in Japan: “Manga developed after World War II at the hands of one designer, Osamu Tezuka. He was influenced a great deal by the work of Carl Barks - the creator of Scrooge McDuck 3. Basically, Tezuka made an American art form Japanese by mixing Disney with sophisticated stories. In the US, McCarthyism lobotomized comics, reducing them to this one genre of costumed superheroes. But in Japan, comics grew into a literary art form: You have romance comics, historical comics, golf comics, sports comics … they’re made for every market and for every taste. Now Disney is taking cues from the Japanese. The Little Mermaid is heavily influenced by the manga style, and The Lion King is basically Tezuka’s ‘Kimba the White Lion’.” - Christopher Couch -Editor-in-chief, CPM Manga 4

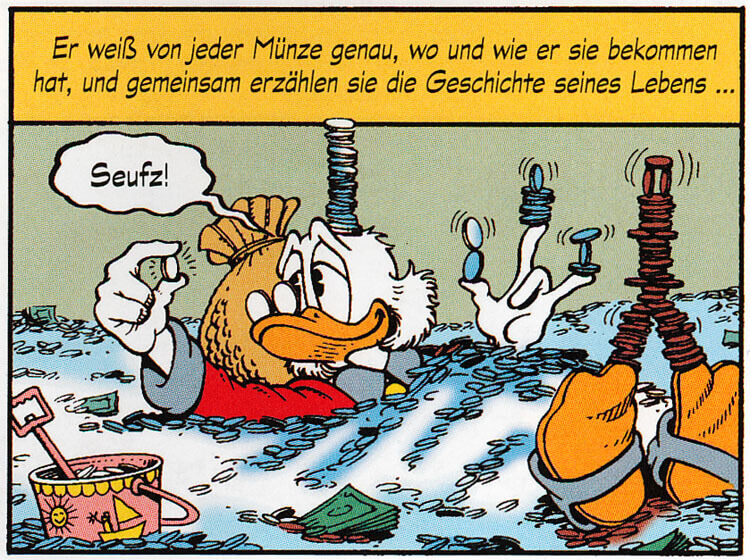

Beyond indirectly shaping the style of Japanese Manga, the Duckburg stories are venerated as literature in Germany and much of northern Europe and outsell all other comic books. (in this we seem to have not only defeated our Axis foes on the battlefield, but also razed their cultures with the memetic timebomb of cartoon ducks). This is primarily due to the insertion of yet another overachiever caught in the act of slumming - In this case Erika Fuchs, a German art history Ph.D. who was given the task of translating Barks’ stories in the 50’s and continued to do so until her death in 2005. In the course of translating, Fuchs was directed to enrich the content of the comics to try and assuage German parents’ fears of encroaching American pop-culture. As a result, the Fuchs-Banks hybrid ducks spout Goethe and sing Wagner.

Take, for example, the classic Duck tale “The Golden Helmet,” a story about the search for a lost Viking helmet that entitles its wearer to claim ownership of America. In Dr. Fuchs’s rendition, Donald, his nephews and a museum curator race against a sinister figure who claims the helmet as his birthright without any proof—but each person who comes into contact with the helmet gets a “cold glitter” in his eyes, infected by the “bacteria of power,” and soon declares his intention to “seize power” and exert his “claim to rule.” Dr. Fuchs uses language that in German (“die Macht ergreifen”; “Herrscheranspruch”) strongly recalls standard phrases used to describe Hitler’s ascent to power. 5

Music from “Duck Tales Wanpaku Duck Yume Bouken”, better known as “Duck Tales, the Game” (1990 Capcom)

In 1987, Disney - a company that for most of its history existed by merchandising the character design that it owned from its animation projects, was in a post-Walt slump. Its animation had been de-emphasized in favor of live action (1981’s The Fox and the Hound, which had the then depressed and marker-sniffing Tim Burton on its animation staff 6, was the closest thing Disney had to an animated hit in the 80’s). Disney planned on making a foray into television animation in an attempt to win back some of the child mindshare that had been irrevocably lost to the funnier and more frenetic Warner Brother’s cartoons in the 1940’s.

Unfortunately, Disney’s intellectual property had always depended on pillaging fairy tales and buying characters from dead artist’s estates- there was very little in the way of a richly detailed and charactered disney franchise that would make good fodder for a serialized cartoon. Disney’s first attempts- “The Wuzzles” and their Smurf clone “The Gummi Bears” were met with lukewarm response. Finally, rediscovering the wealth of Barks’ work, Disney’s “Duck Tales” cartoon was a huge success, and may have indirectly led to the brief (and quickly squandered) renaissance of Disney feature animation in the early 90’s (Aladdin, The Little Mermaid). As it was, “Duck Tales” was reportedly the first American animated TV series to be syndicated in the former Soviet Union.

As a child, my only connection to Disney animation was the “Duck Tales” cartoon which I’d watch when I got home from school… And the fact that, when I was an infant, my mother put up Mickey Mouse drapes in my room which terrified me and lead to reoccurring nightmares about being stalked by Mickey (with his giant eyes and maniacally happy mouth). Divorced from any knowledge of what a cartoon supposed to represent, the almost abstract stylization of these characters can be disturbing to a still-forming mind. I don’t think I even realized Mickey was supposed to be a mouse, just some grinning bubbly-headed thing (I certainly have no childhood memory of ever seeing a Mickey Mouse cartoon).

In 1995, the huge demand for Scrooge comics in Germany and Northern Europe led Disney to commission new comics. Cartoonist and Barks fan, Don Rosa, used this as an opportunity to meticulously comb through every Carl Barks’ duck book and produce a series of comics (collected as “The Life and Times of Scrooge McDuck”- out of print due to licensing issues, but supposedly new editions are in the works). Rosa won the Eisner Award for “Best Serialized Story” for his Scrooge work, and in the process, produced some of the most exhaustive footnoting and organization of the Barks comics. (He also drew that creepy picture of Scrooge’s grave that begins this article.)

Barks is fascinating to me for a couple of reasons. First, because he’s a perfect example of a man given a tiny, dreary corner in which he can be creative, and instead of going through the motions (how many people would brighten at the idea of drawing ducks for the rest of their lives?) he poured his soul into it, and channeled a rich inner life into a universe of ducks (I wonder if when he closed his eyes he saw hordes of anthropomorphic ducks, chasing him through his dreams?). At the same time, in writing this article, I came across such serious and studied devotion to Barks and his work, that I feel like he is a prime example of the flip-side of an artist pouring his heart into commercial entertainment: he’s an artist who people work feverishly to read stuff into. One of the weird aspects of the time we live in is that people would rather read between the lines of pop culture to find spiritual and emotional succor than go pick up a comparitievly medicinal work of ‘high art’ that deals with things directly. Either through nostalgia or ignorance or some other coy form of intellectual perviness, people would rather guess what someone is trying to say about life by sifting through hundreds of comics about talking ducks than read a ‘real book’. Our collective story is being codified into mass media, which as a commodity must be accessible to children under 10 (and children over 30) to survive. If it sounds like I am taking a duck-crap on “Duck Tales” and on Disney, I’m not. This harsh environment of scribbling in the margins makes some of the oddest, most layered, but still accessible art- and it gives us some of the most interesting characters to talk about. Not Scrooge McDuck, per se, but the weirdo who created him, and the weirdos who obsess over him.

This disturbing exploration into the nature of evil in both Ducks and Beagles comes from the amazing FatalFarm.

-

The Duck with the Bucks- Time Magazine ↩

-

Check out this New Year’s card that Tezuka wrote to Barks in admiration. ↩

-

Wired Magazine - Ichiban (top ten Japanese influences on western culture) ↩

-

Why Donald Duck Is the Jerry Lewis of Germany - The Wall Street Journal Online ↩

-

Burton on Burton (Faber&Faber press) ↩