This is project start for Phantom Homeland, an art installation.

I’m spending the holidays in my home town of Austin, Texas. It’s a city that is cyclically purged of successive populations born to it– currently by rising rents and property taxes. The Austin airport is filled with functioning museum-versions of restaurants that have been forced out of business in the city itself, and live on only as simulacra valued for the residual branding they offer the city. I’m old enough that I’ve seen several waves of people pushed out of the city along with their businesses and arts venues, so it’s hard to get angry about it now. I only feel a sort of dim, directionless displacement here. With friends and relatives scattered and having been in Los Angeles a few years for school, I don’t really feel at home anywhere.

I’m spending the holidays in my home town of Austin, Texas. It’s a city that is cyclically purged of successive populations born to it– currently by rising rents and property taxes. The Austin airport is filled with functioning museum-versions of restaurants that have been forced out of business in the city itself, and live on only as simulacra valued for the residual branding they offer the city. I’m old enough that I’ve seen several waves of people pushed out of the city along with their businesses and arts venues, so it’s hard to get angry about it now. I only feel a sort of dim, directionless displacement here. With friends and relatives scattered and having been in Los Angeles a few years for school, I don’t really feel at home anywhere.

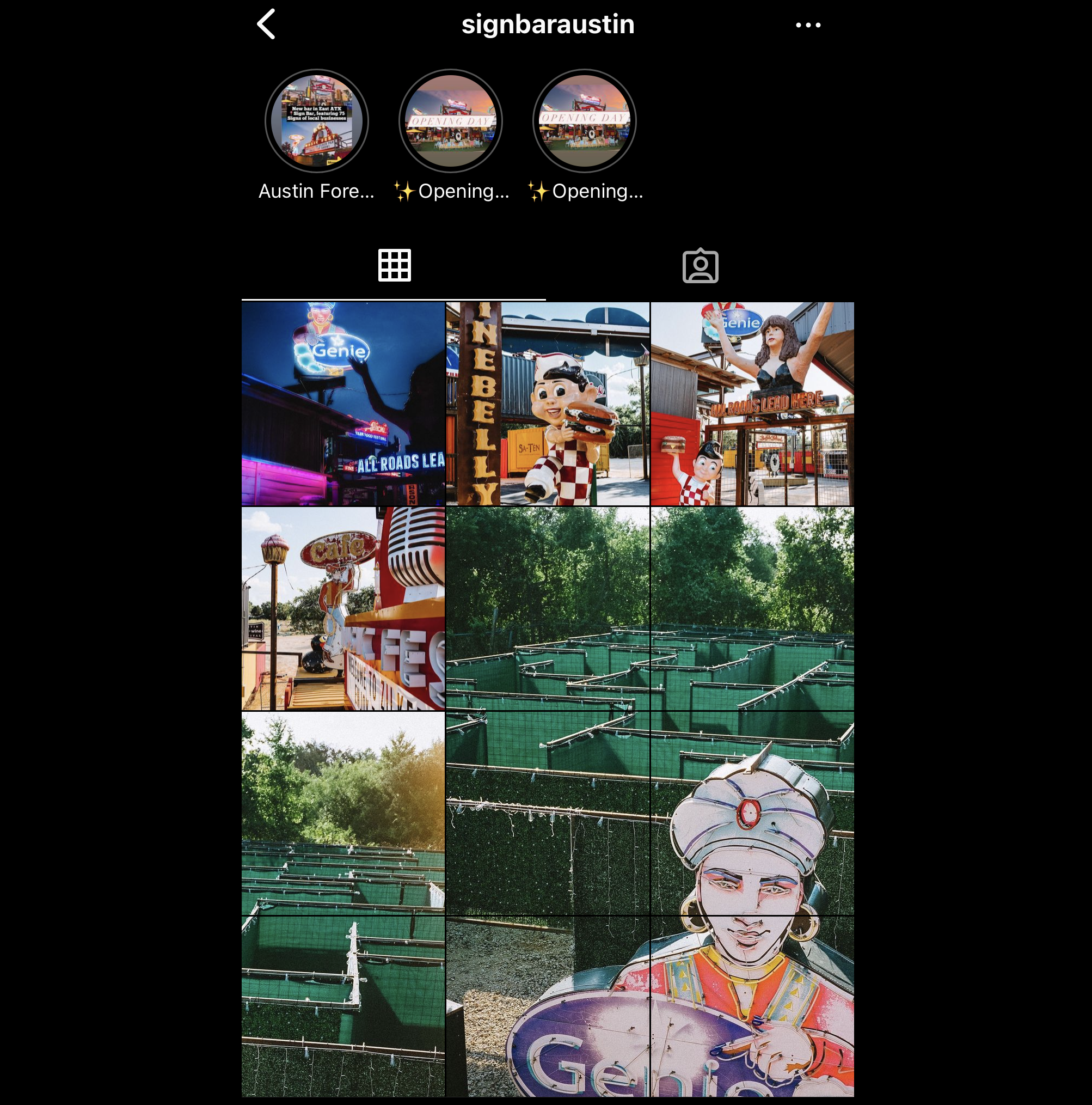

- The instagram account of “Sign Bar”, a new themed cocktail bar that has purchased the signs of iconic Austin businesses that have closed and arranged them as decorations for an upscale bar *

In the next few days we are anticipating a cold snap that brings back memories of the winter storm that hit Texas in 2021, which resulted in a massive, prolonged power outage and a handful of deaths from exposure and smoke inhalation. The state is assuring us that the power grid will withstand the usage surge this year, but this promise may hinge on the voluntary actions of Texas’ massive infestation of parasitic cryptocurrency miners , who were paid by the state’s energy provider ERCOT to reduce their energy consumption during this summer’s heatwave (Chiu). Texas is both a site of fossil fuel extraction and of energy wastes that flow from that extraction, a symbol of entrenched petrochemical power with a puppet state government that seems to exist primarily to serve that power.

I’m staying with my elderly mother who lives in a small, somewhat dilapidated house in northwest Austin surrounded by two-story luxury homes that have sprung up around it. The other houses seem embarrassed of hers, waiting for her departure so that the plot of valuable property can be liquidated. The home was a HUD foreclosure that she and her father purchased for $32k after her divorce in 1988. In Austin’s current housing market the property is probably worth twenty-five times that now. Her faucets leak, the roof over the porch-slab slumps. “You’re sitting on a gold-mine,” one of our townie relatives tells her with an edge of urgency. The house may be a little run down, but it is a house, and it’s no small thing that we had it when I was growing up, her father was a WWII vet who moved up in class from a wilderness subsistence farmer to a skilled laborer after being trained in construction during his time in the Navy and then benefiting from the G.I Bill. He was able to step in when we needed help. In the years that followed WWII, G.I Bill benefits were notoriously earmarked as white-only, creating a compounding disparity in multigenerational wealth between white and minoritized soldier’s descendants. The promise of upward mobility, now dwindling for anyone in the working class, was often predicated on its exclusions.

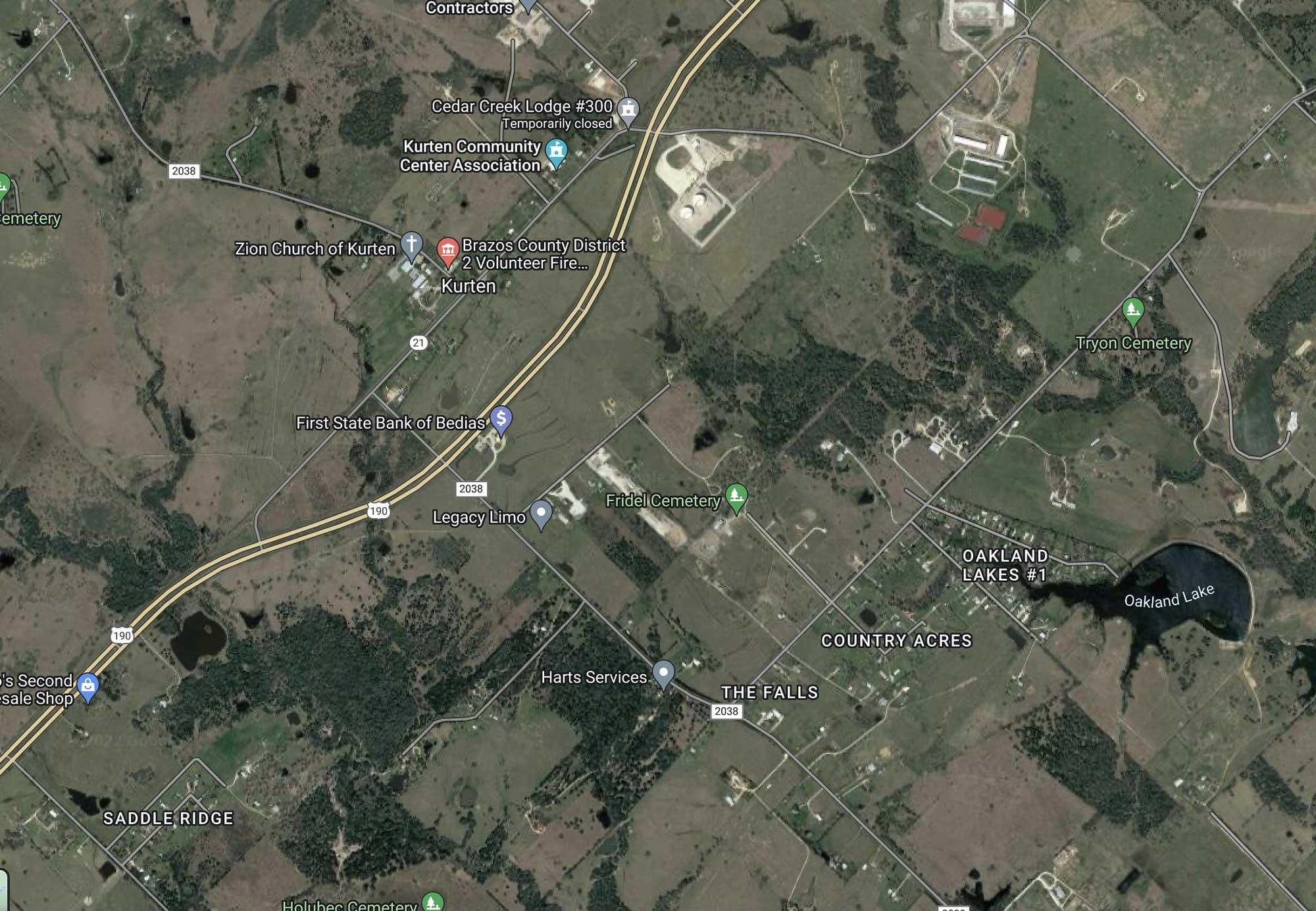

My mother lives frugally off of social security and sporadic small checks she receives because of her share in the mineral rights from a family farm. My family on my grandmother’s side were Moravian immigrants to Texas who arrived here after the civil war. They worked as laborers and then managed a plot of farmland in the town of Kurten Texas for a hundred years. After the last generation of our family living on the farm died or were moved to assisted living, their heirs (including my mother) parceled the land out and sold it after years of disagreements. While the property held little residential value (electricity had been connected but there was a well and an outhouse rather than plumbing) or value as modern farmland, the farm became valuable instead for the trickle of oil that had been found on it sometime in the 90’s. The mineral rights and revenue stream from the haphazard spurts of oil were divvied up among the families, who drifted further apart. I think sometimes about how many generations of family lived together and worked the land on that farm. Certainly I would have found a life there stifling, but I wonder about how the land and its history was traded away for abstract value. But again, we were lucky– while some could sell their land, others simply had it taken away, or their rights to it delegitimized.

My family landed in Galveston in 1879, finally settling in Kurten in 1882 in a community that had already been a German/Slavic enclave for some time. I wonder often who lived on the land in Kurten before the Moravians and their farm. The town was founded in 1864, near the end of the civil war, some time after anglo settlers (under the leadership of Steven F. Austin) murdered and dispersed the native Karankawa people who had lived along the Brazos river (originally known as the Tokonohono). There may have been Tonkawa or Comanche people using the area at one time as well.

I’ve taken some time over the past few months to read both Greg Grandin’s The End of the Myth and Sean M Kelley’s Los Brazos de Dios to try to build a mental model of the the idea of Frontier as a zone of freedom from restraint and construction of imagined identities and communities as a justification for violence and territorialization. I’m beginning to kick around a project that centers the idea that power can have no objective justification, it finds its excuses in constructed mythologies and skewed histories. I know from Kelly’s work that in 1860 the lower Brazos area to the south of my family farm was a majority Black population (55%) with a very small Hispanic and Indigenous population (Grandin 20). I have less information about the populations of the river bottoms of the upper Brazos and Navasota. These areas were less desirable than the lower Brazos lands that were run as plantations, but they were an important foothold area for immigrants and some freed enslaved people after the civil war. Henry Kurten, a German soldier, had purchased a Mexican land grant there in 1864 and created a pipeline for chain migration, where German immigrants could work his land and then establish farms of their own (missing reference). During the time that Texas was a slave state, the Germans were seen as an oppositional culture– using a family labor system to work their land.

Networks rooted in German identity were vital, not only to the passage itself, but to the eventual acquisition of land. To be certain, the pattern in which older migrants employed newer ones brought occasional charges of exploitation, but in most cases it worked. Terry Jordan found that over 77 percent of German farmers owned their own land in 1850, compared with 69 percent of Anglos. In Cat Spring, 71 percent of German households owned property in 1850, and more than 80 percent did in 1860.

(Kelley)

When German chain migration slowed, Slav laborers like my family were brought over with the same promise of land. Lured by a letter from a Silesian minister published in a Moravian newspaper promising tracts of plentiful and cheap land, nearly half of the first boat of Czech immigrants died in the crossing or of yellow fever when they reached Texas (Kelley).

Kurten Texas

Kurten has a population today of about 150, and my Moravian family’s cemetery is still there, surrounded now by mostly scrub and agricultural areas. There’s industrial land use in the area but city ordinances seem to provide some protection from polluting industries (Kurten Zoning Ordinance). Looking at google maps, I was surprised to see my family cemetary clearly marked.

I’m woolgathering at this level of detail about a cemetery in a town of 150 people because as I trace these events in my life and the lives of my ancestors that hinge on place, migration and class traversal, I am reminded of the readings I’ve done about populations whose ancestral burial places and land go unmarked and are overtaken by polluting and extractive industries– in particular the “Death Alley” section of the Mississippi River and the nearby Parish of St. James, profiled in a Forensic Architecture investigation into environmental racism. The residents of St. James engaged with Forensic Architecture to both locate unmarked burial plots of their enslaved ancestors in areas privatized by polluting industries (such as the Formosa Plastics company) and to track the spread of carcenogenic pollutants from those industries. The St. James city council embraces industrial expansion, and, in a published development plan that grotesquely romanticized the history of slavery in the area, described the contested homes as “current residential, future industrial” areas in their zoning plans.

My relatives came to this country as former peasants of the Austro-Hungarian empire, they stood apart from Texas Anglo society for almost 100 years, with their own language and culture still in place, as well as a connection to the land that they stewarded. Even still, each successive generation dreamed of upward mobility. My great aunts can be seen in a photo working a potato field, gloved and veiled– so that their skin wouldn’t darken too much in the sun, marking their class. A few of those sisters never married because they were shamed out of relationships with protestant men by their Catholic family. My grandmother’s was the first generation to speak primarily English, and she married a non-Czech protestant and left the farm. When my grandfather proved still too poor for her, she left him for his construction foreman, still clawing towards an imagined identity and a false class consciousness.

The cold snap has mostly passed now. Pipes have burst across the city but the power has stayed on.