Archon

September 06, 2022Archon

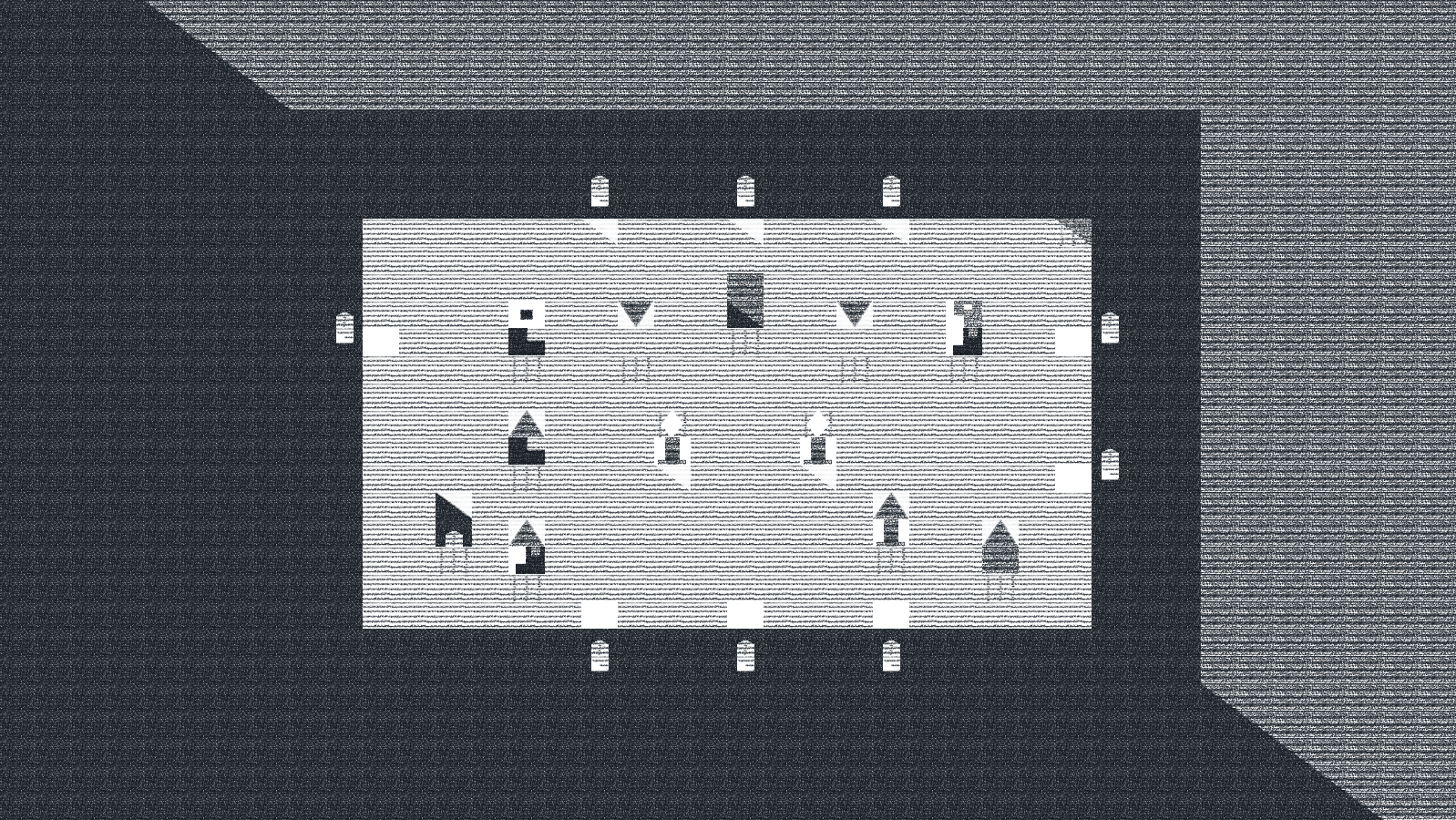

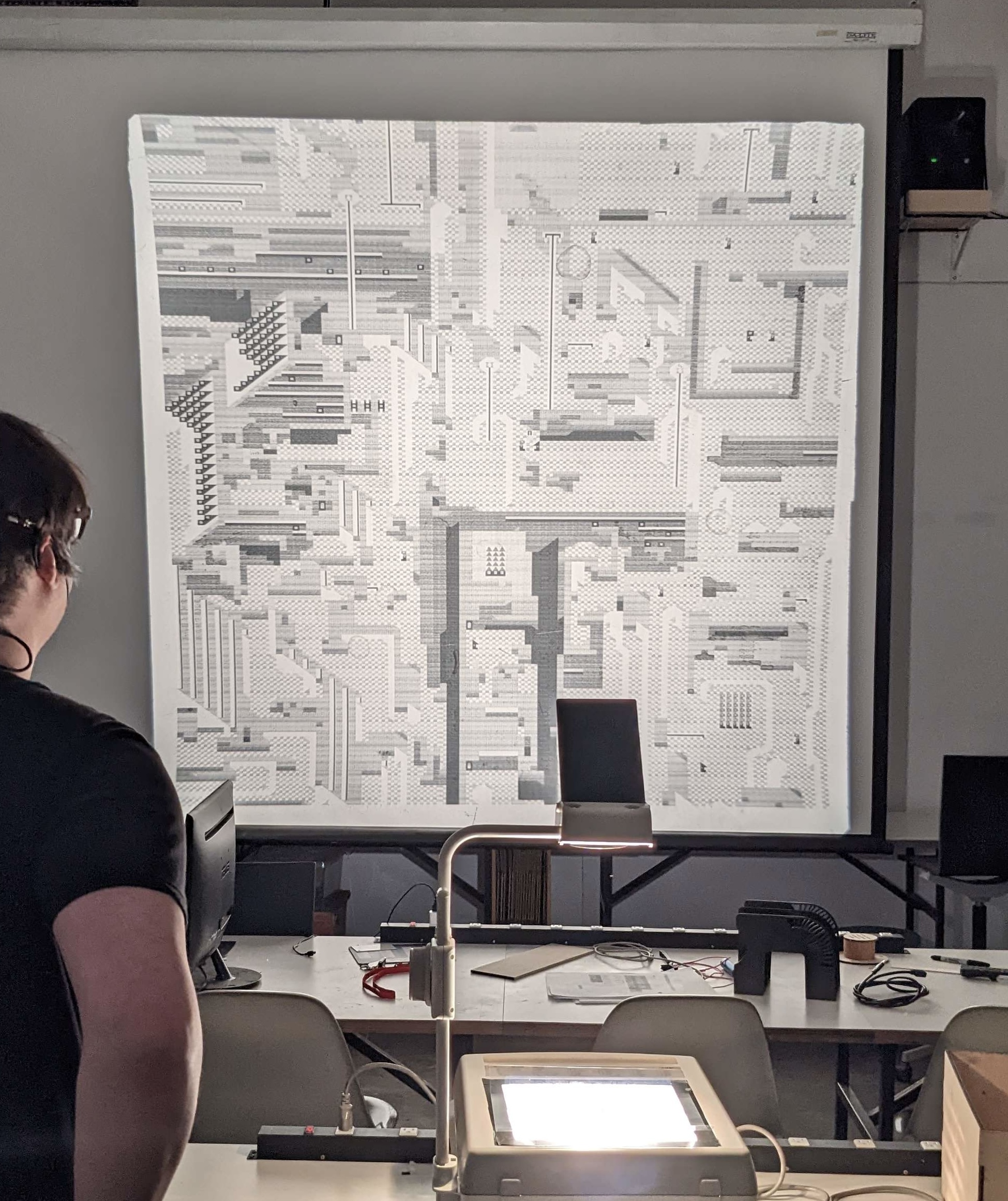

Wooden structures, overhead projector, projection transparency slides, book. Book and slides my be handled.

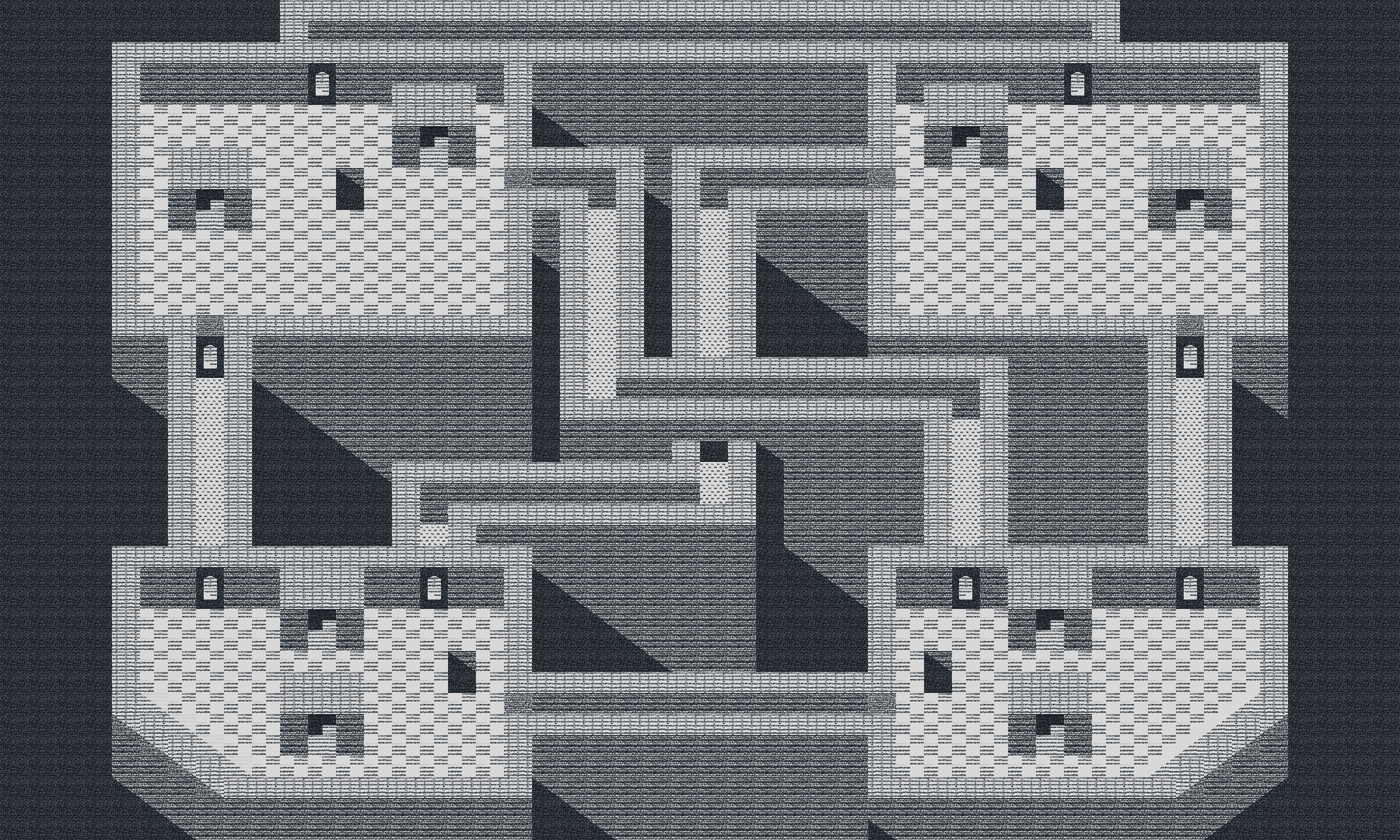

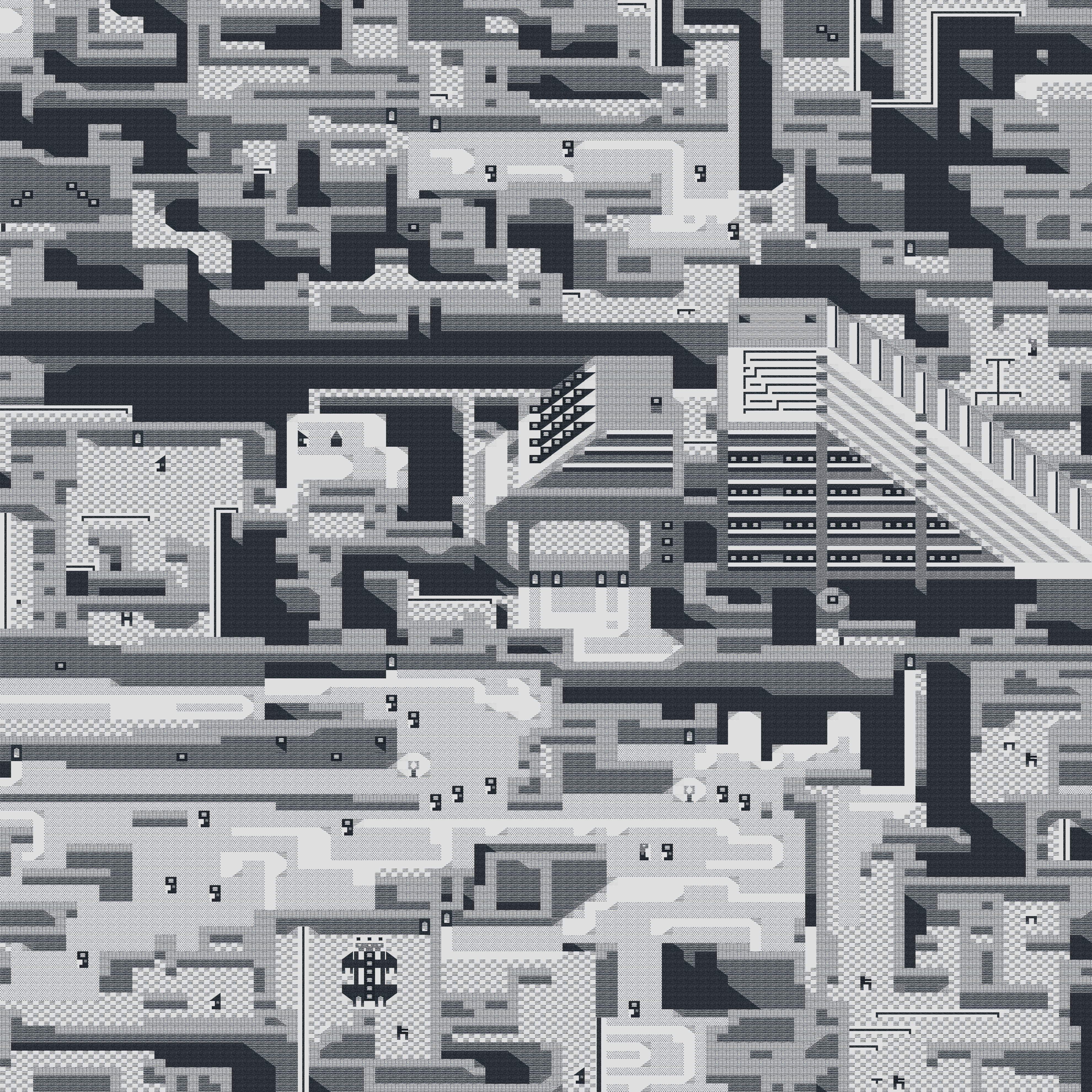

A series of images from an unspecified building game.

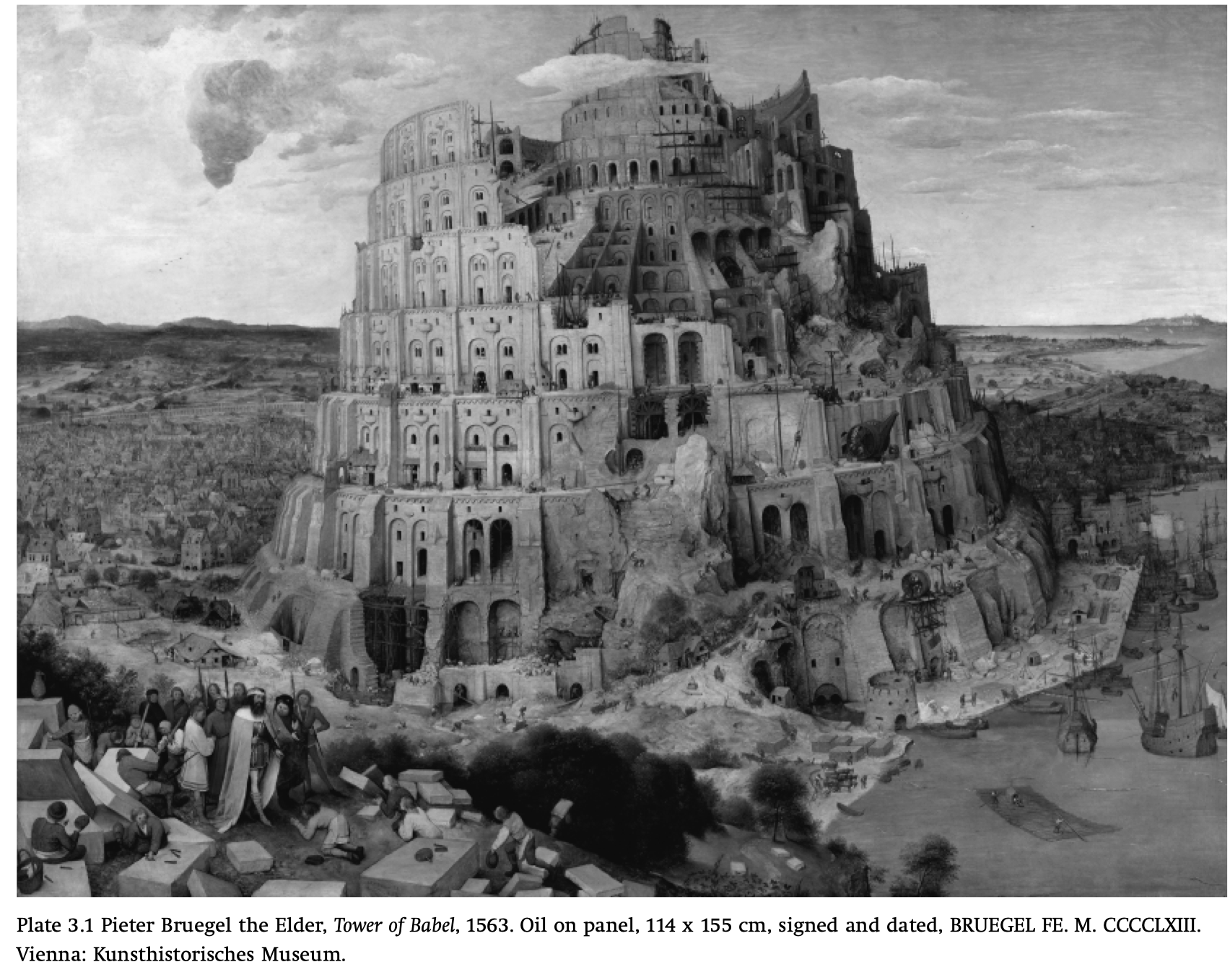

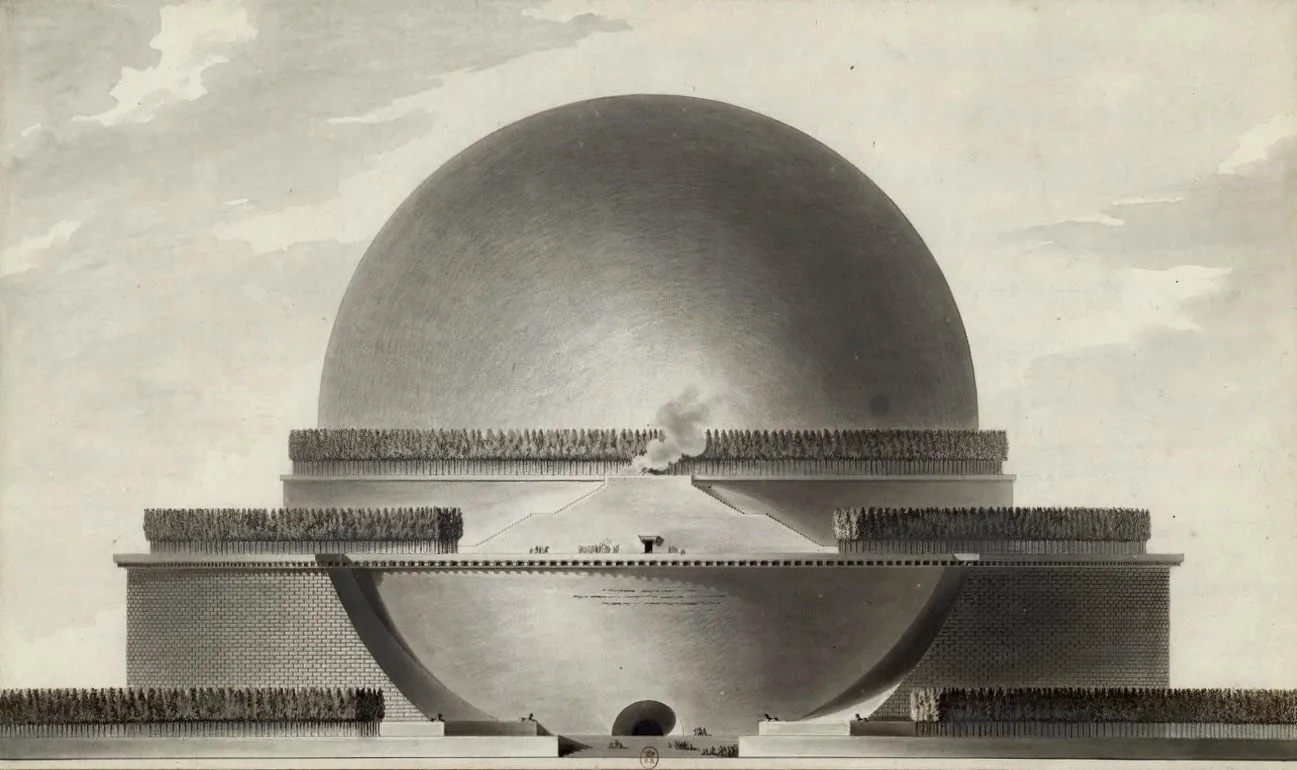

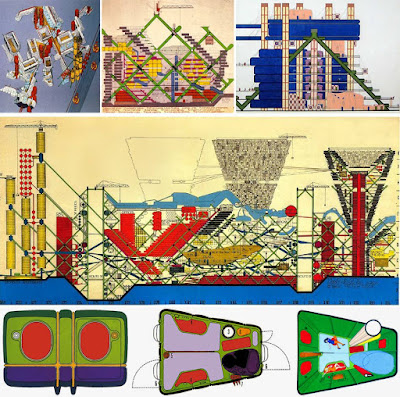

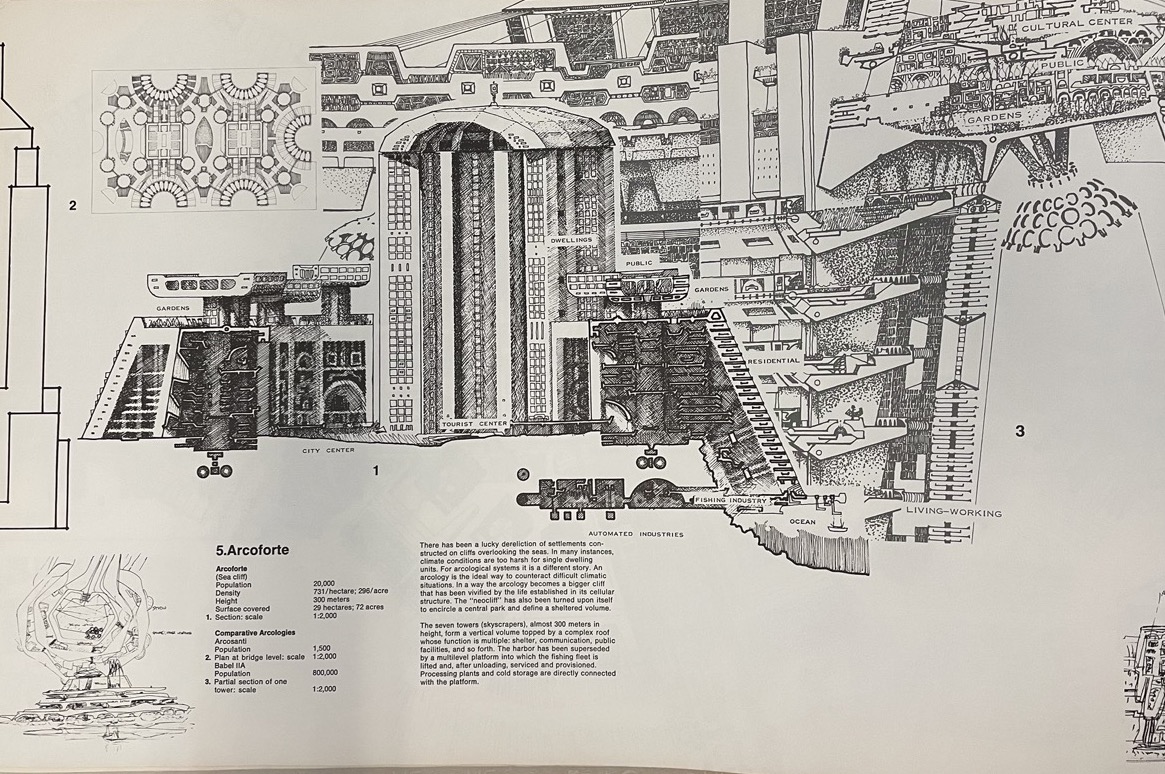

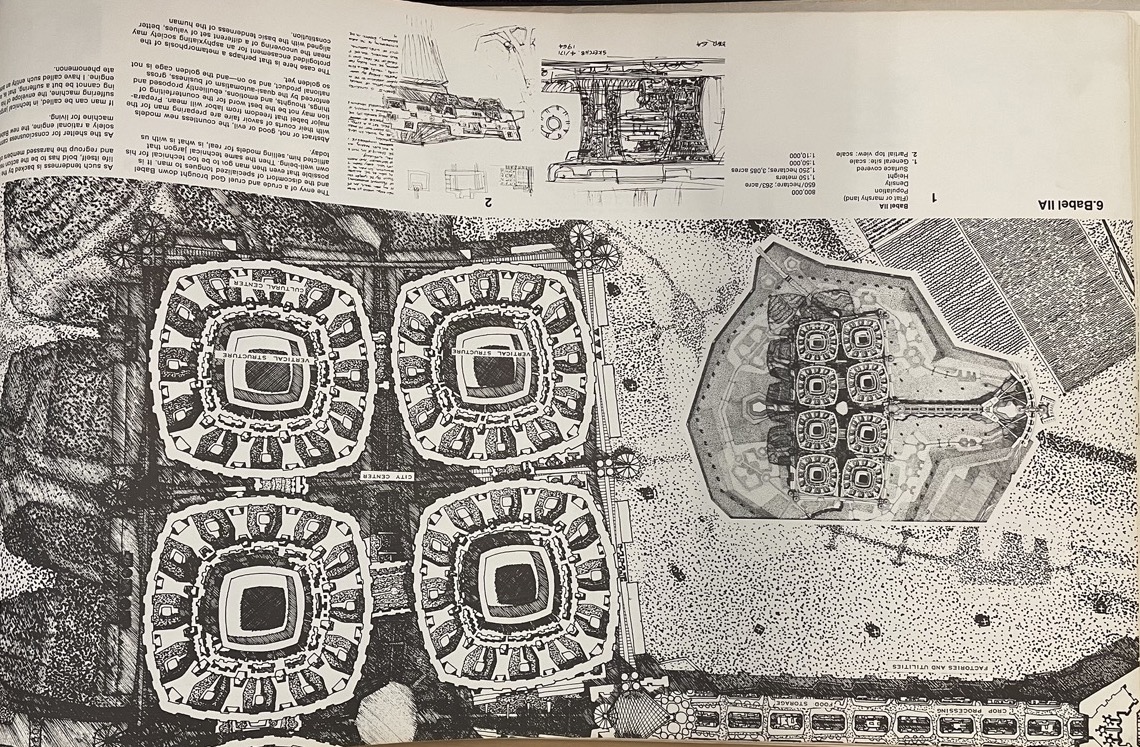

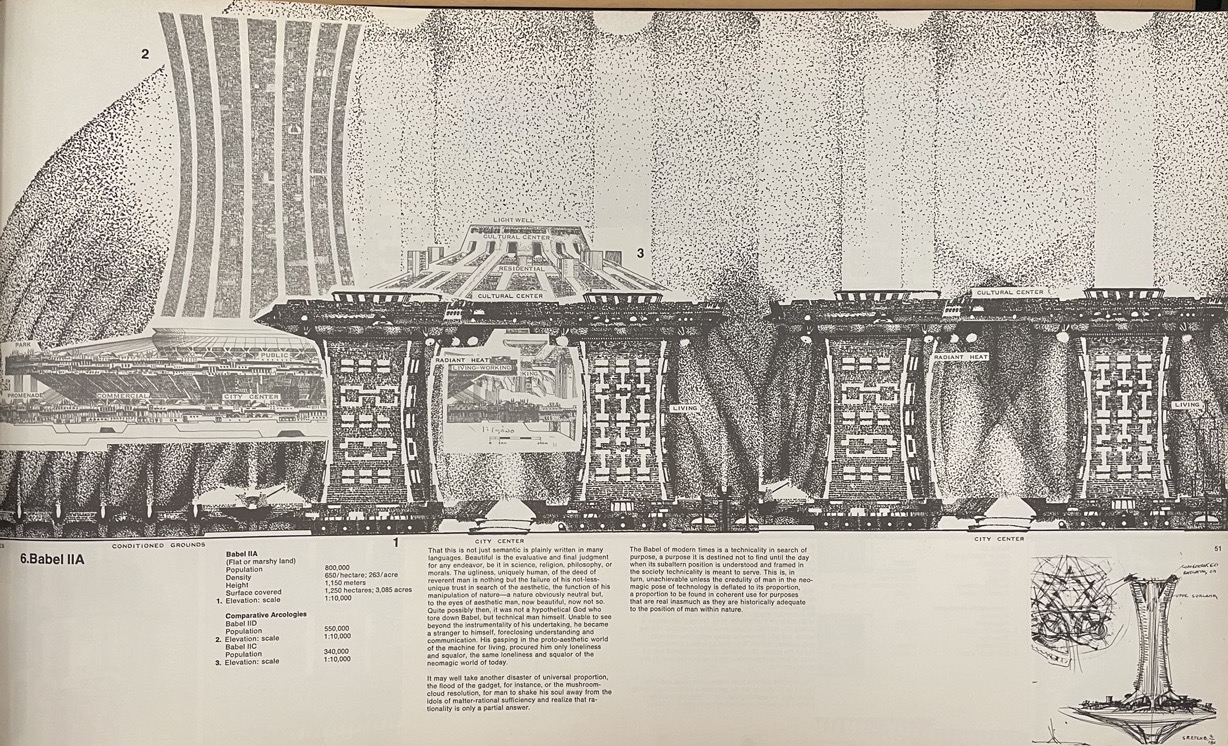

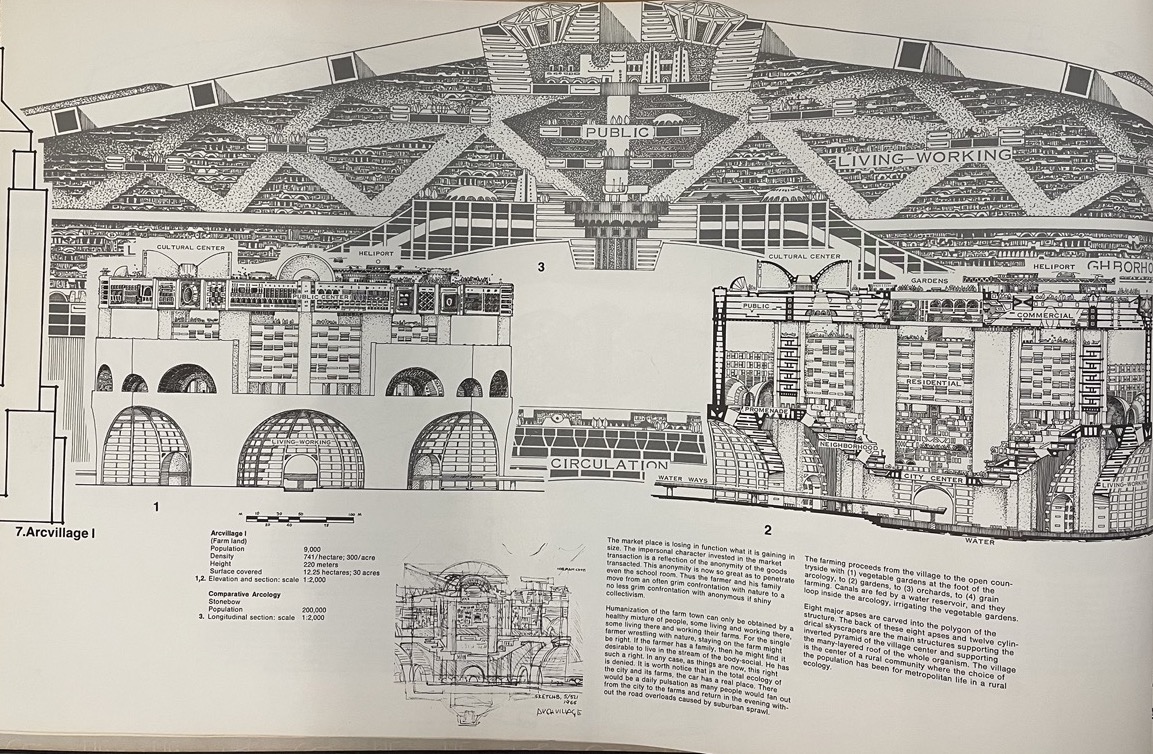

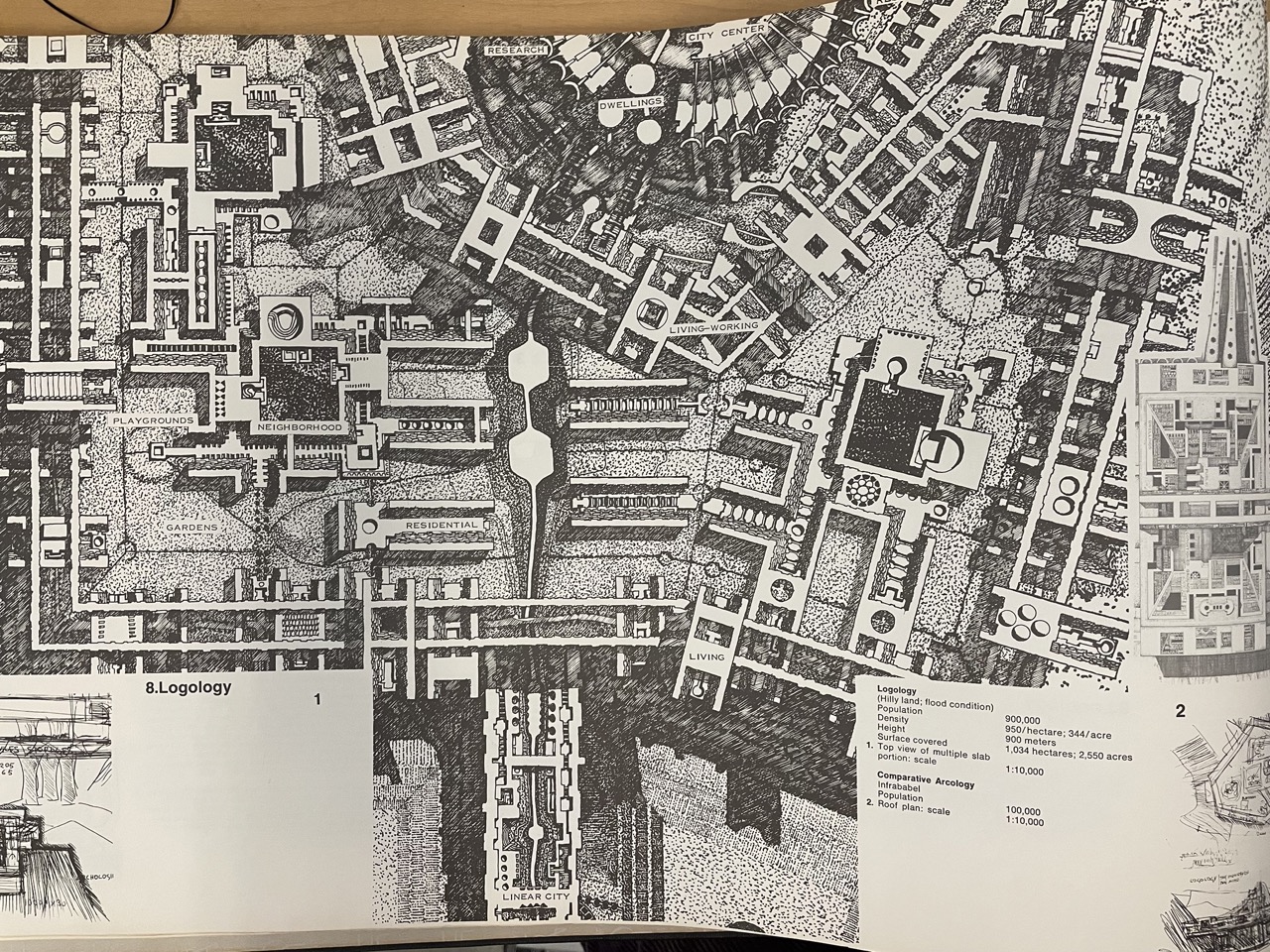

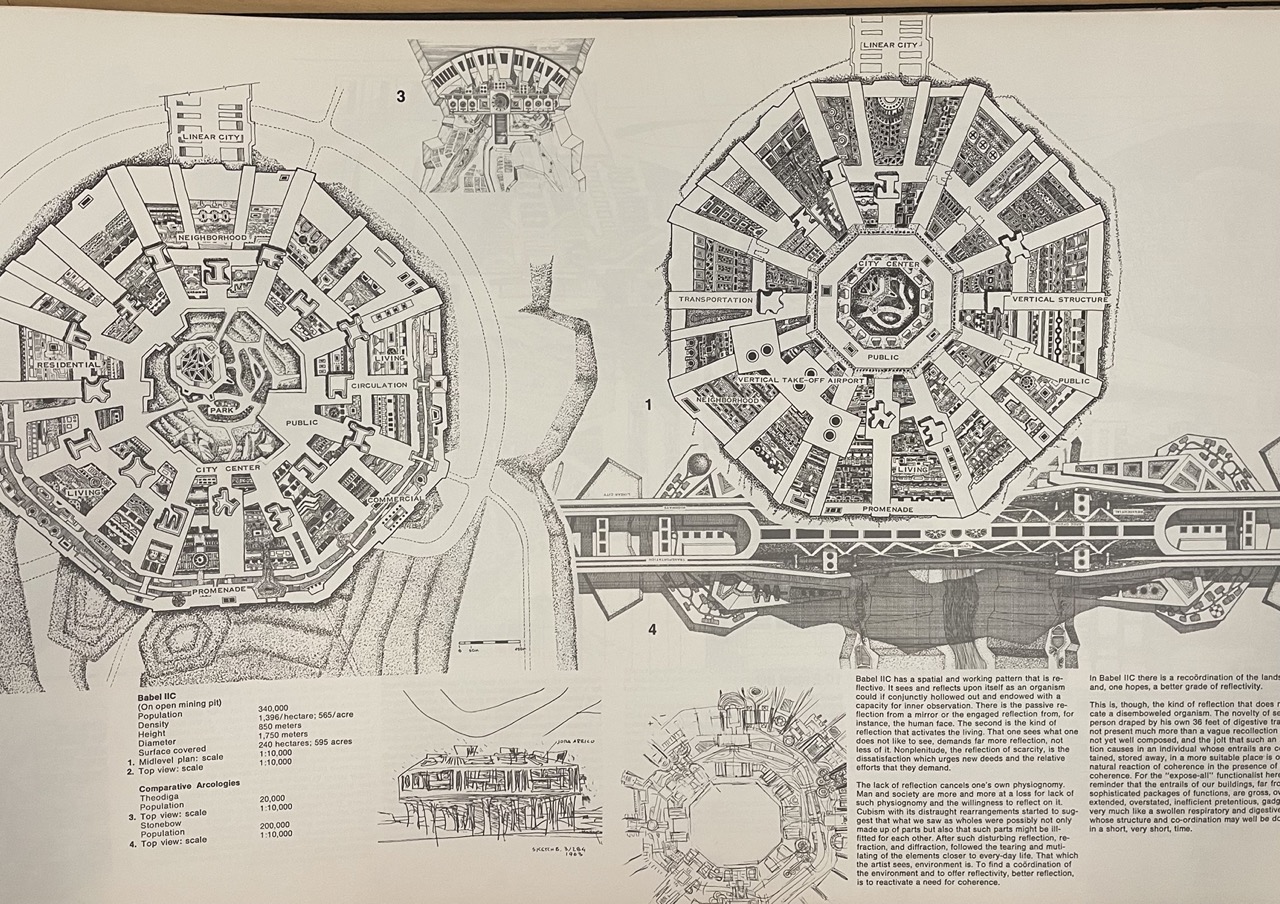

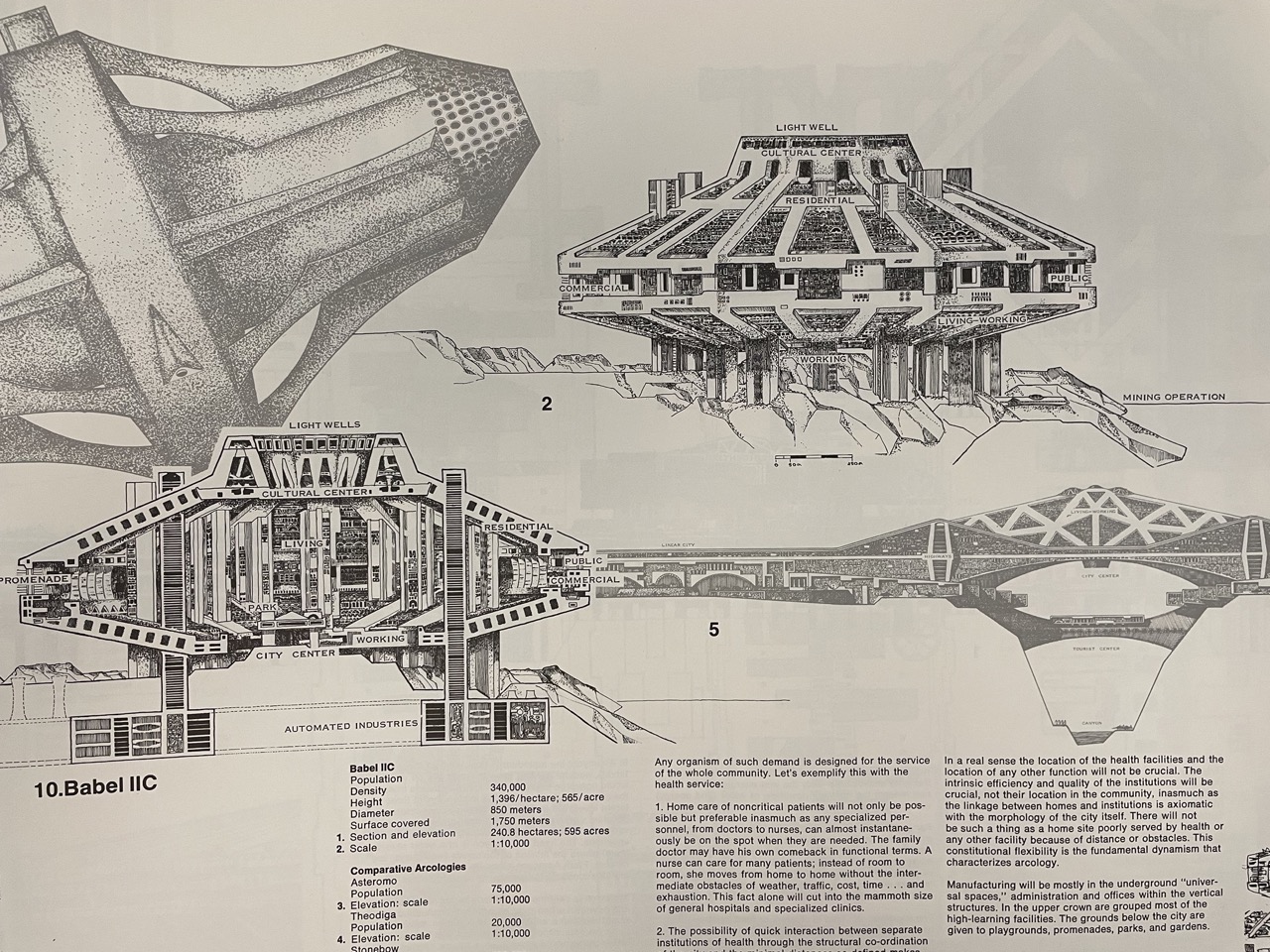

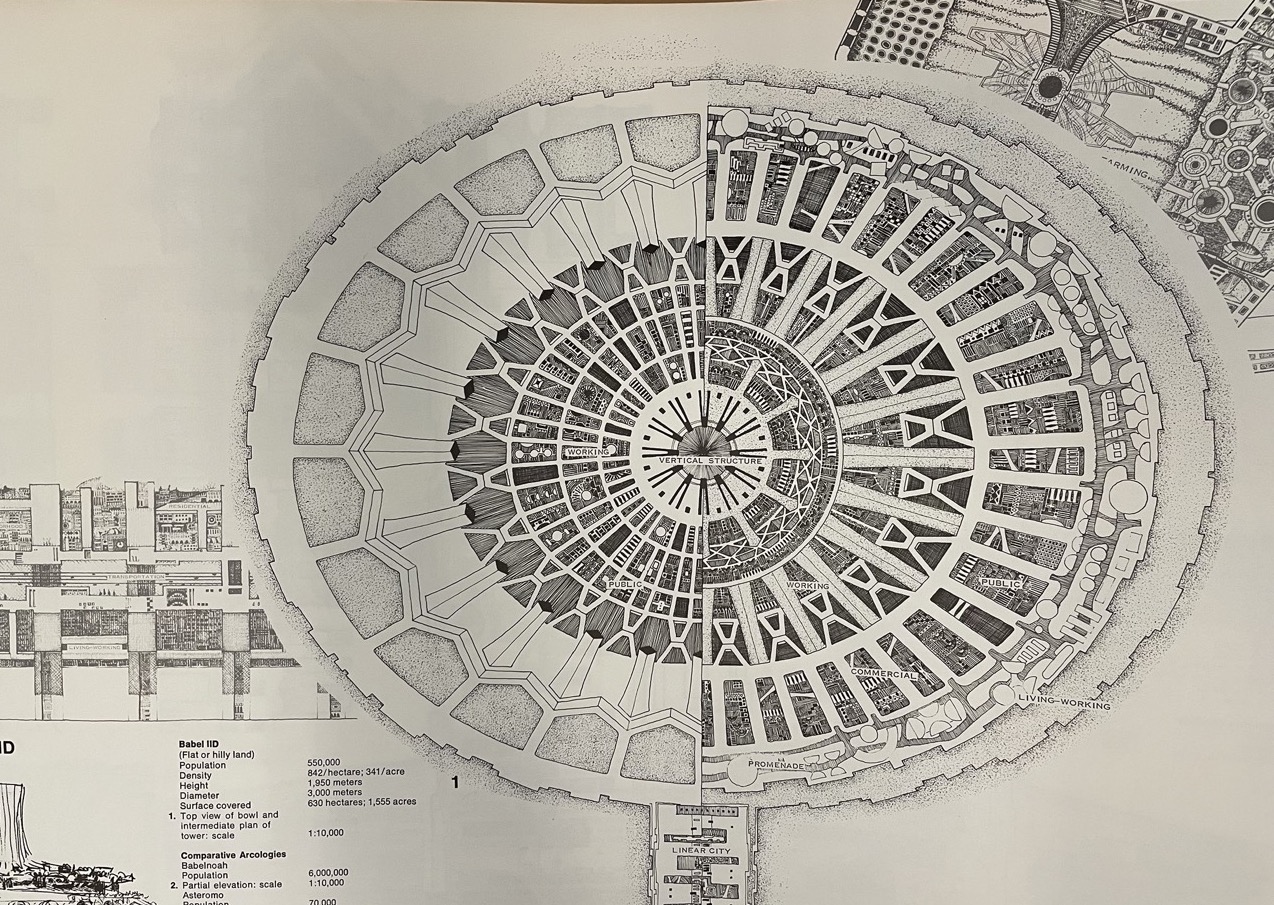

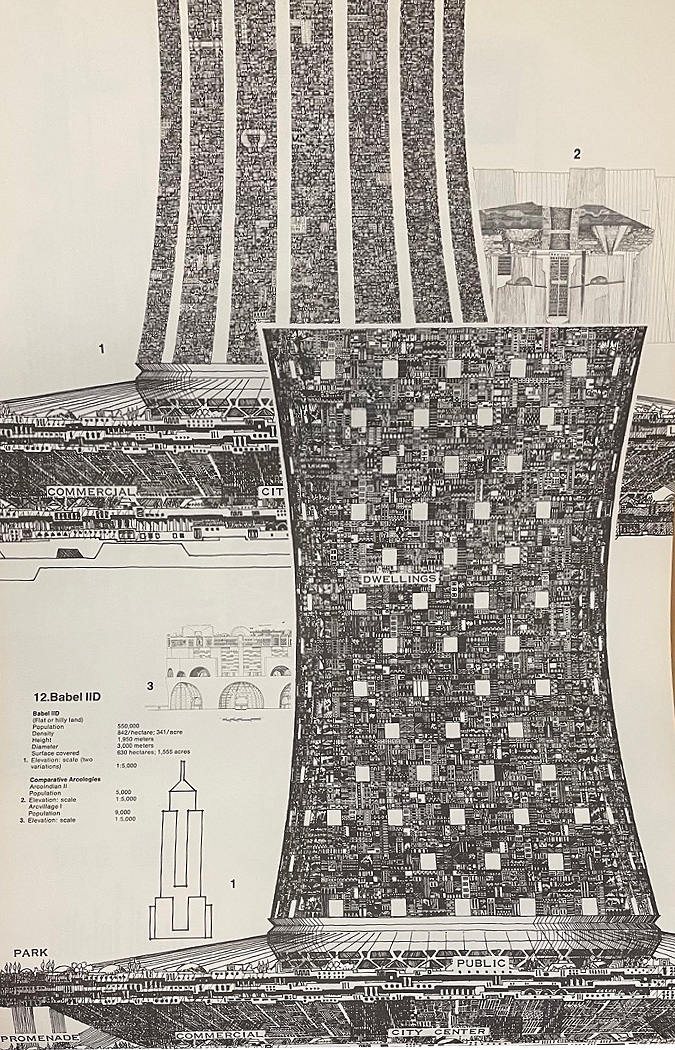

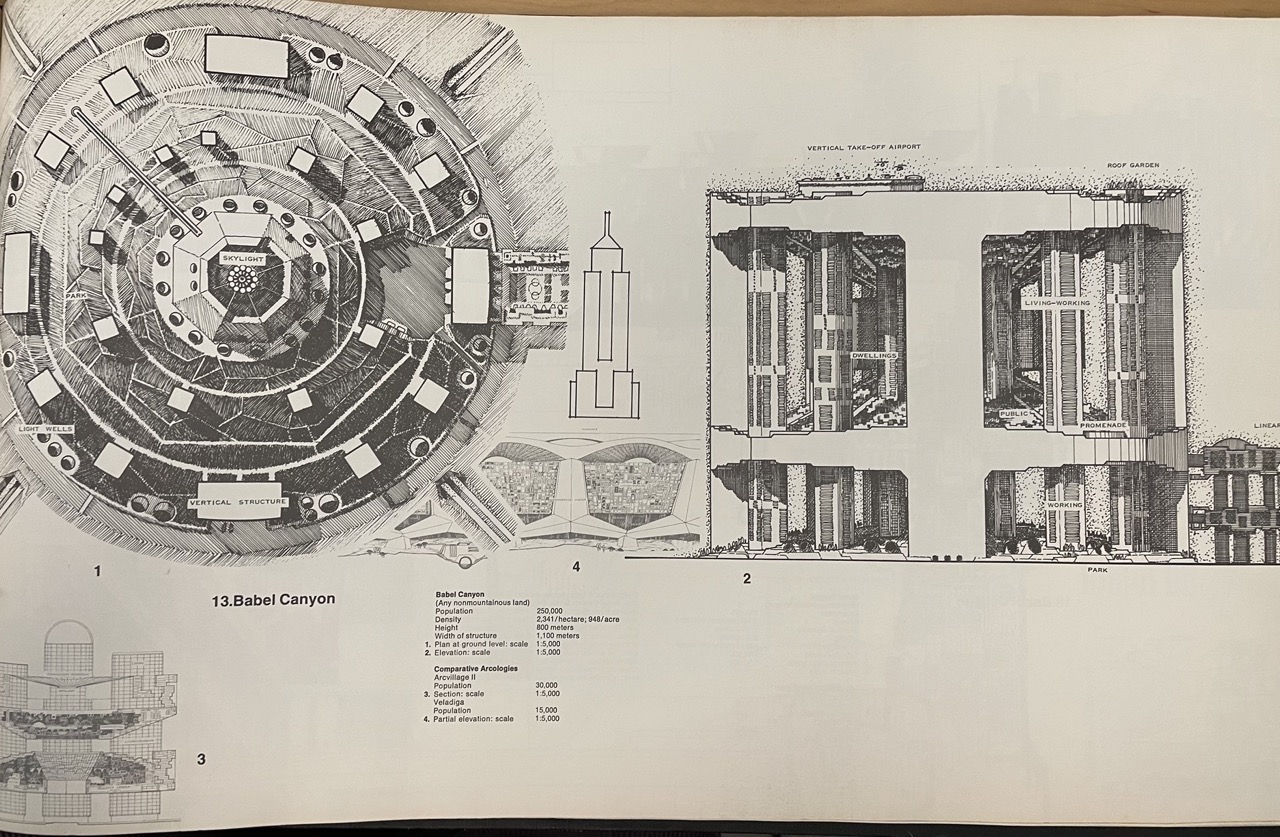

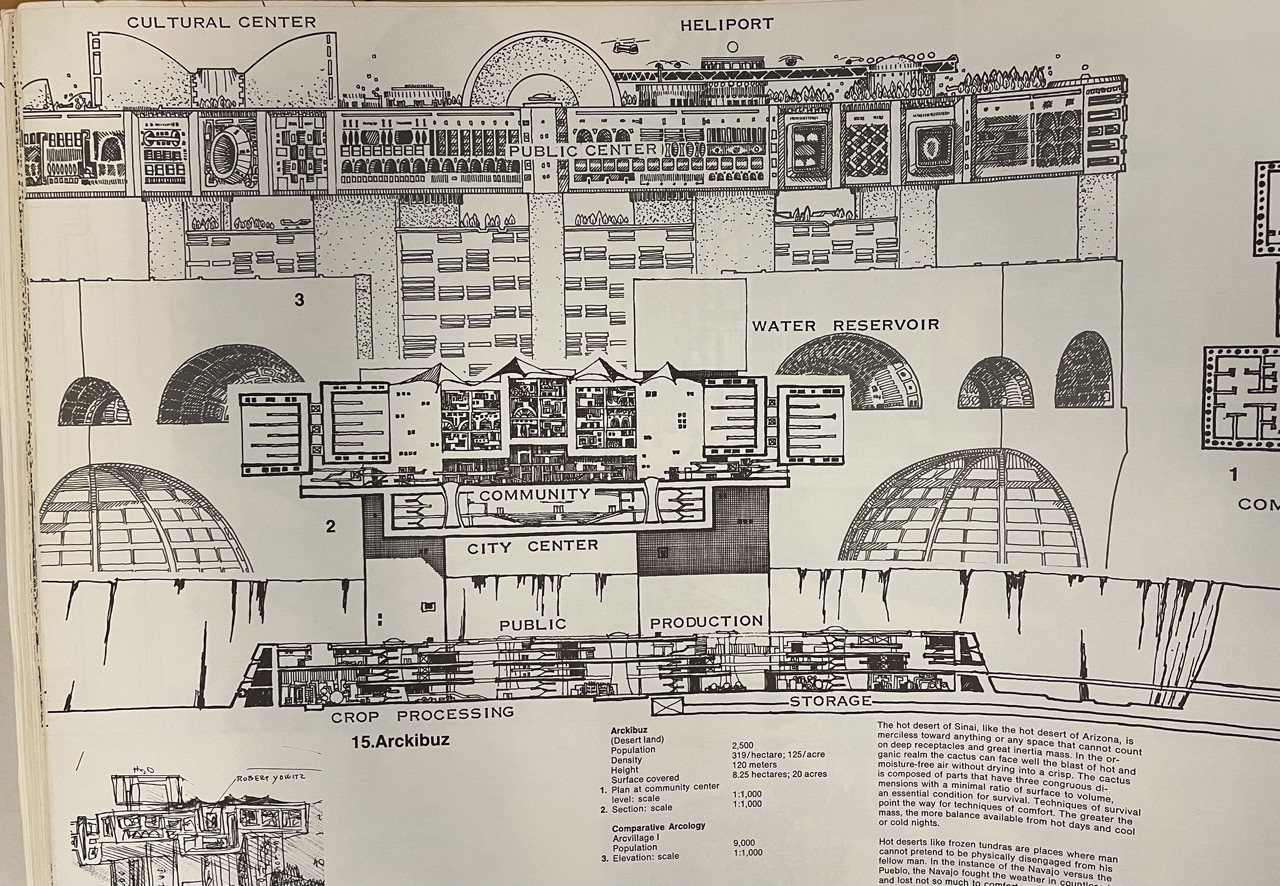

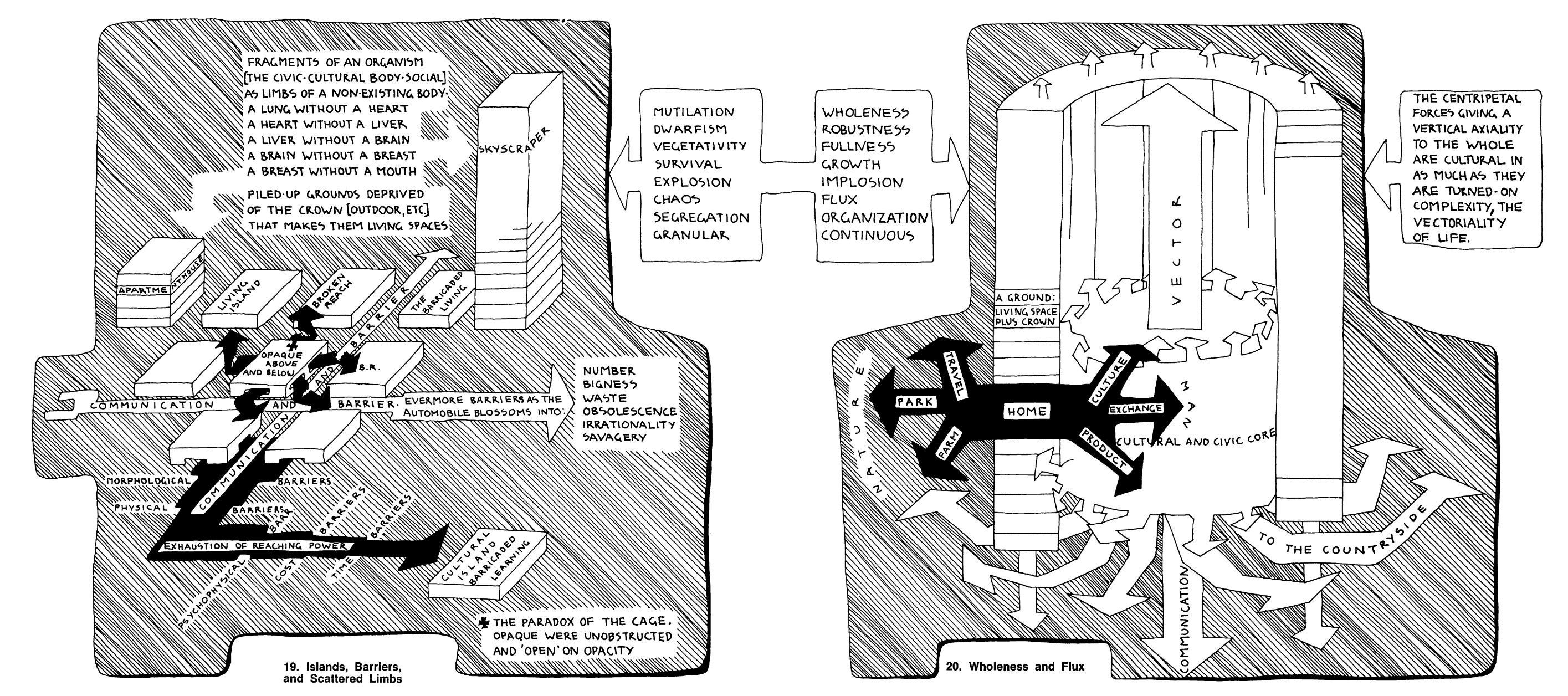

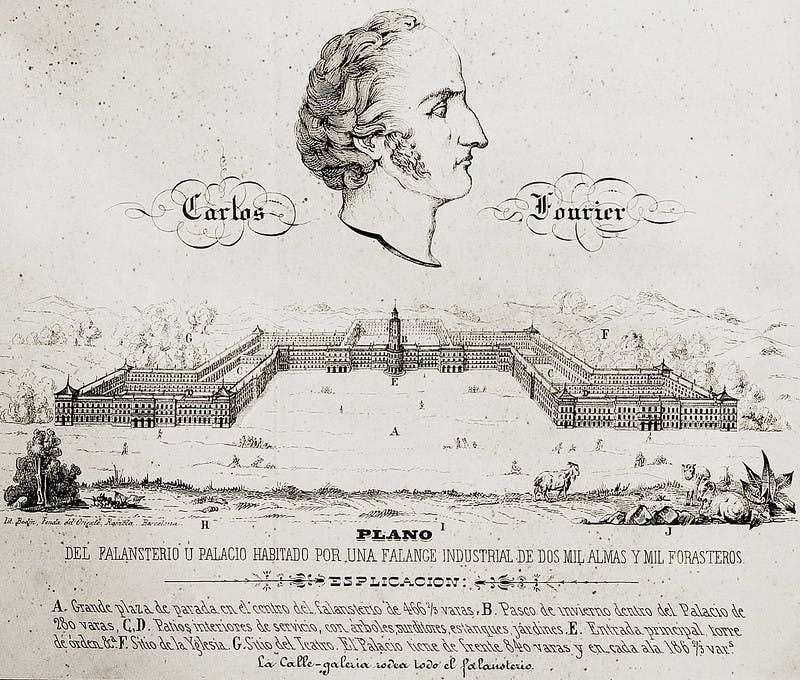

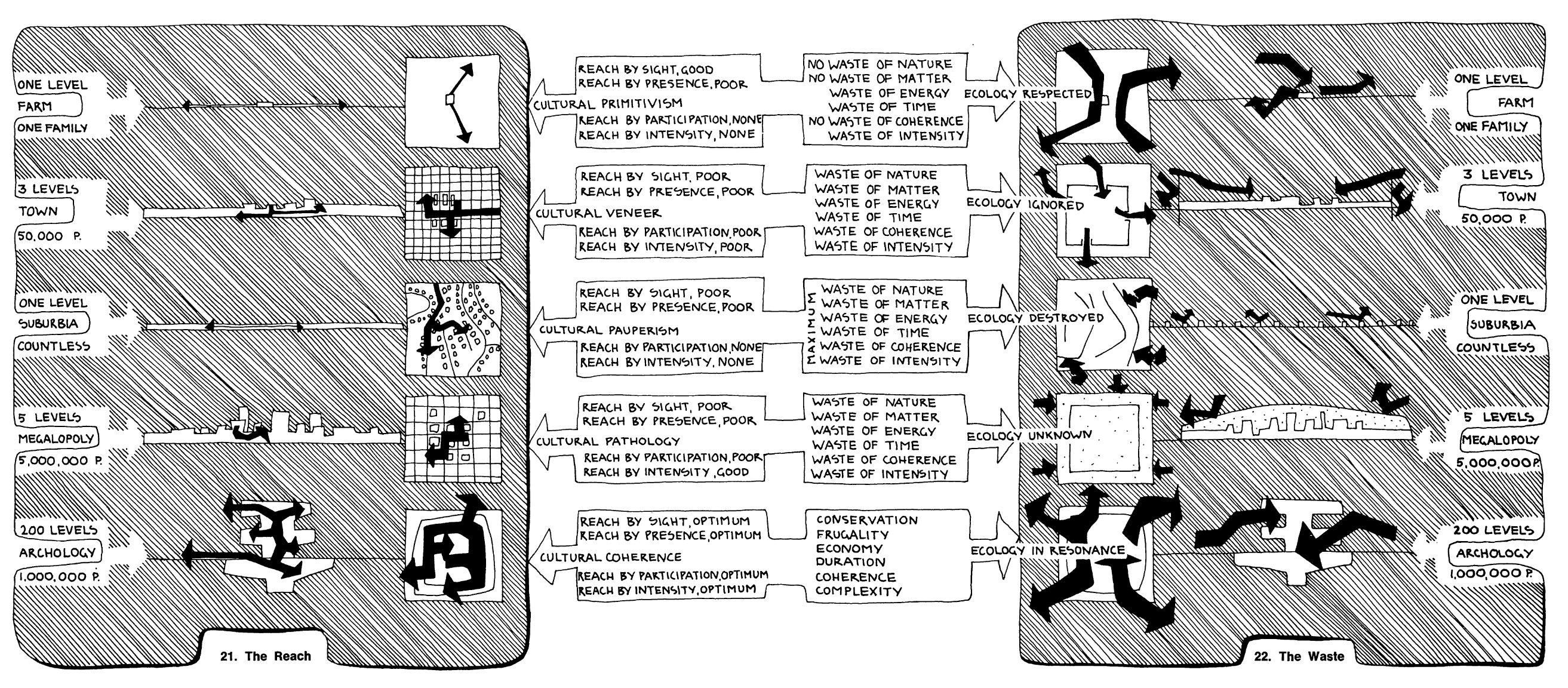

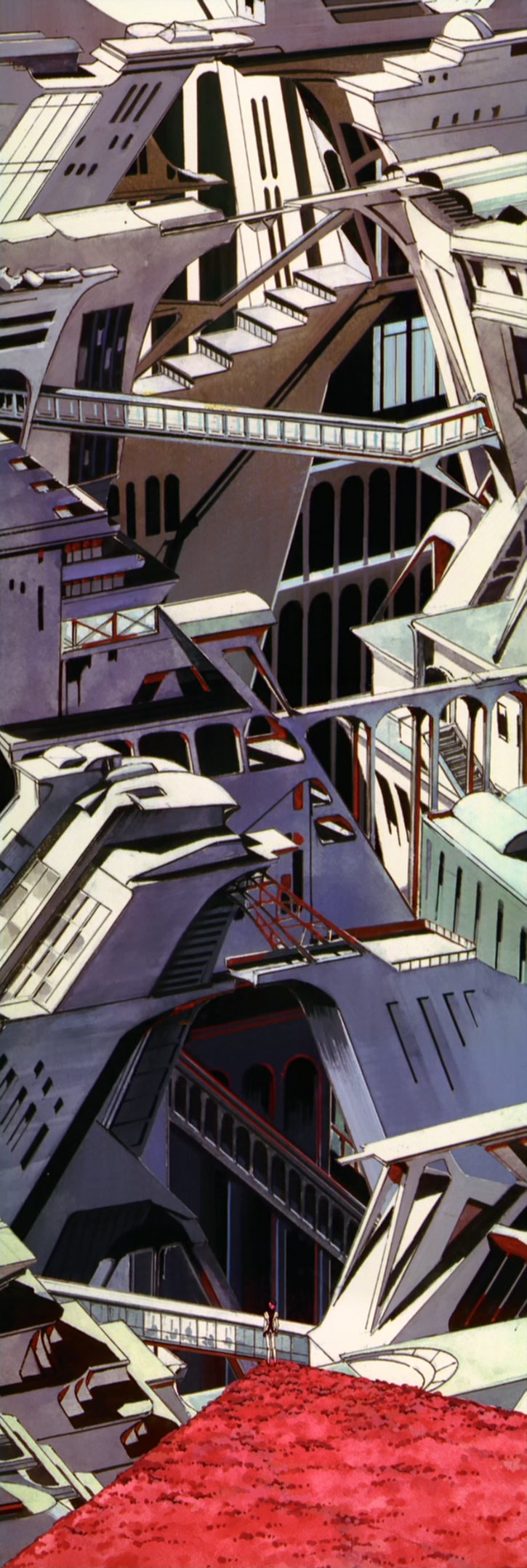

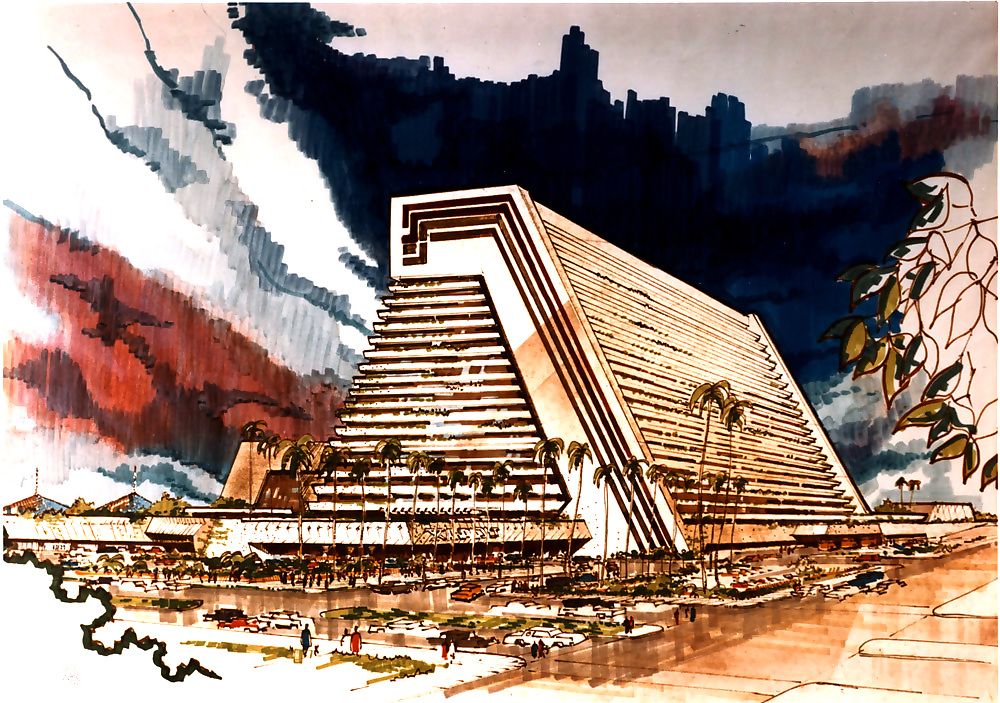

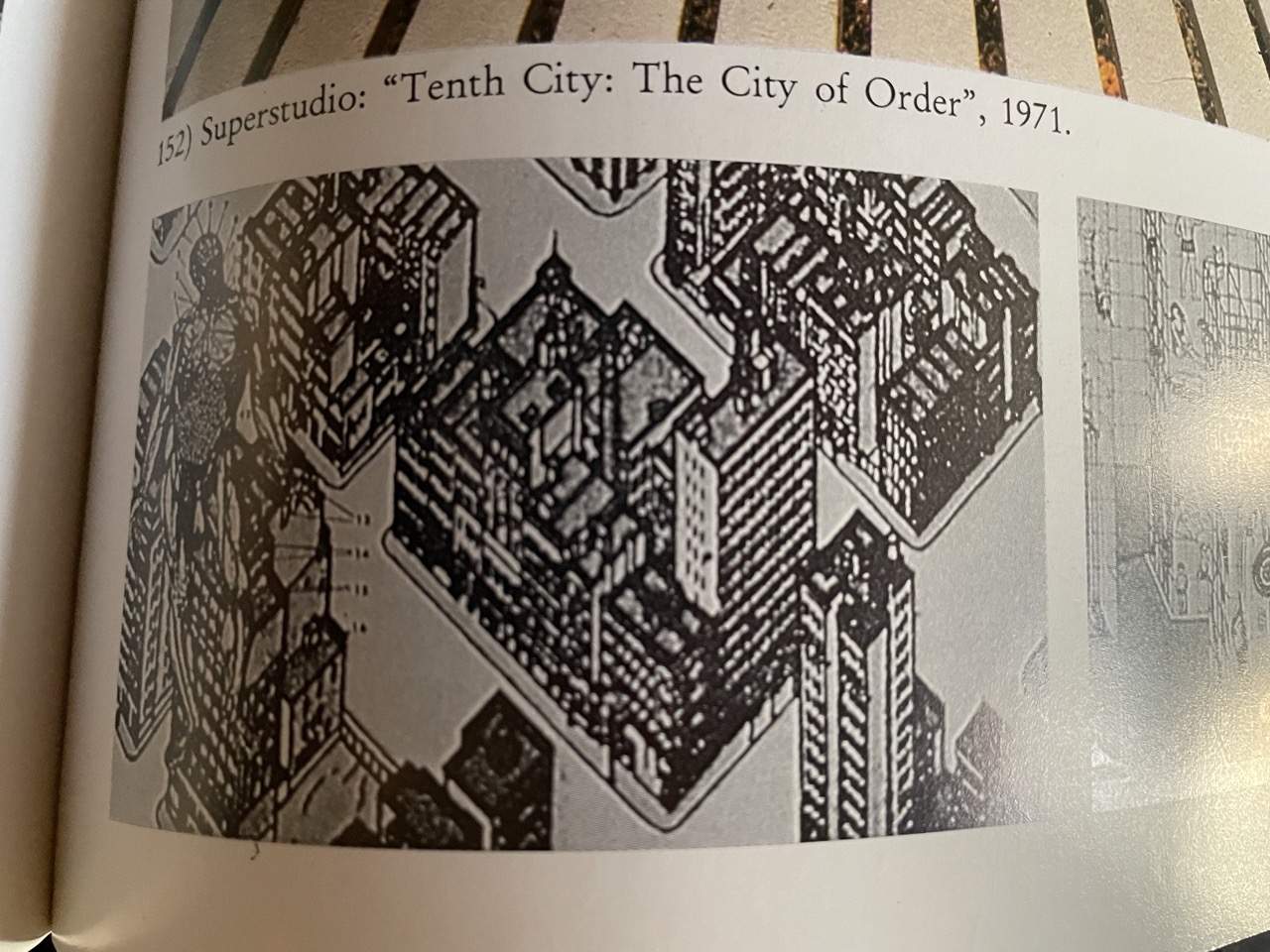

Arcology, a portmanteau of the words “architecture” and “ecology,” is a term coined by artist-architect Paolo Soleri in 1969 to refer to his designs for enclosed-structure megacities. Soleri’s arcologies were meant to incorporate passive climate control and renewable energy sources, eschewing cars and suburban sprawl. Soleri considered these designs to be rough guides rather than prescriptive plans, suggesting that an arcology should be an urban laboratory that harnesses the creativity and will of its residents to direct city growth. Critics of the time, however, perceived visionary megastructures to be authoritarian enterprises.

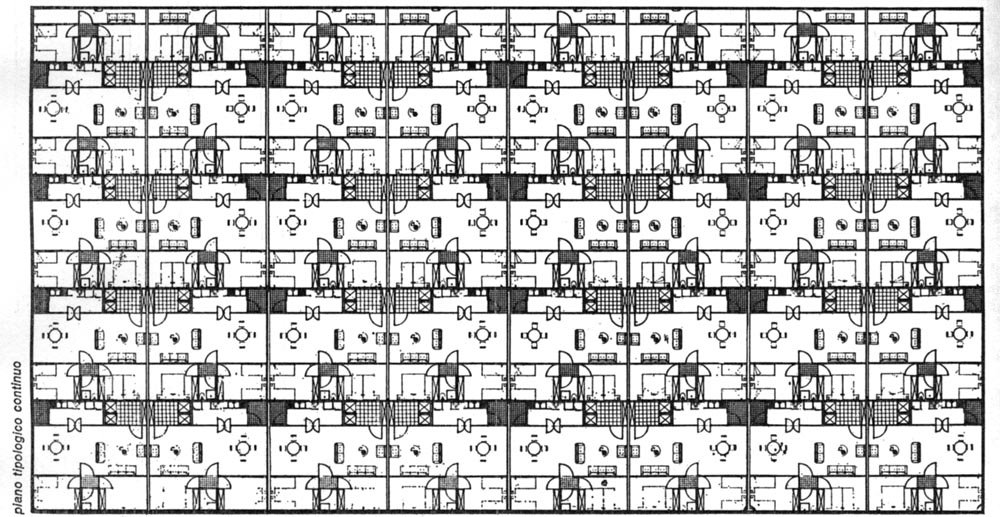

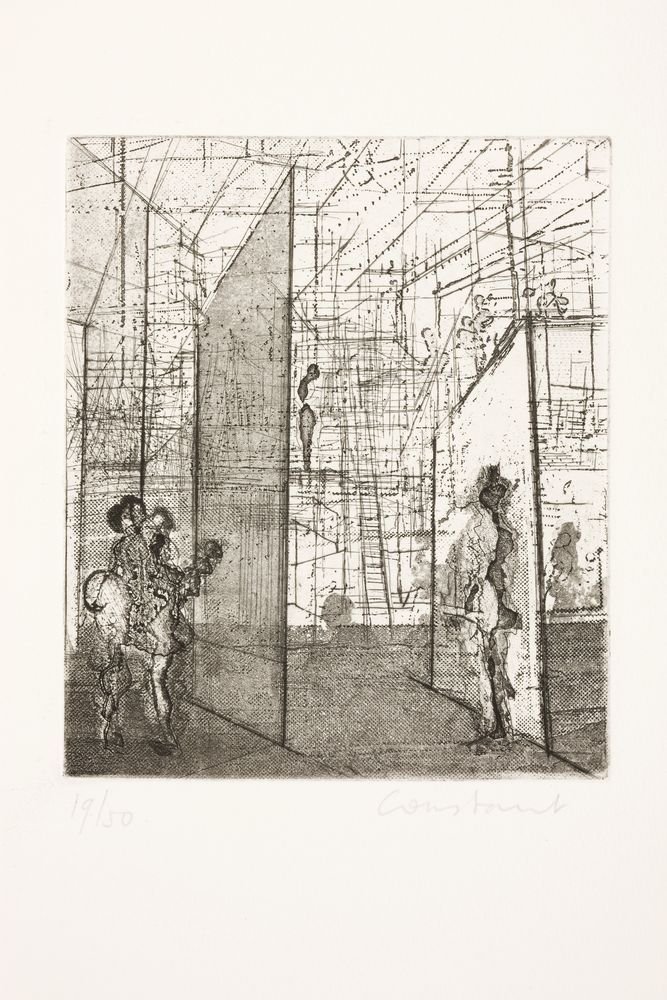

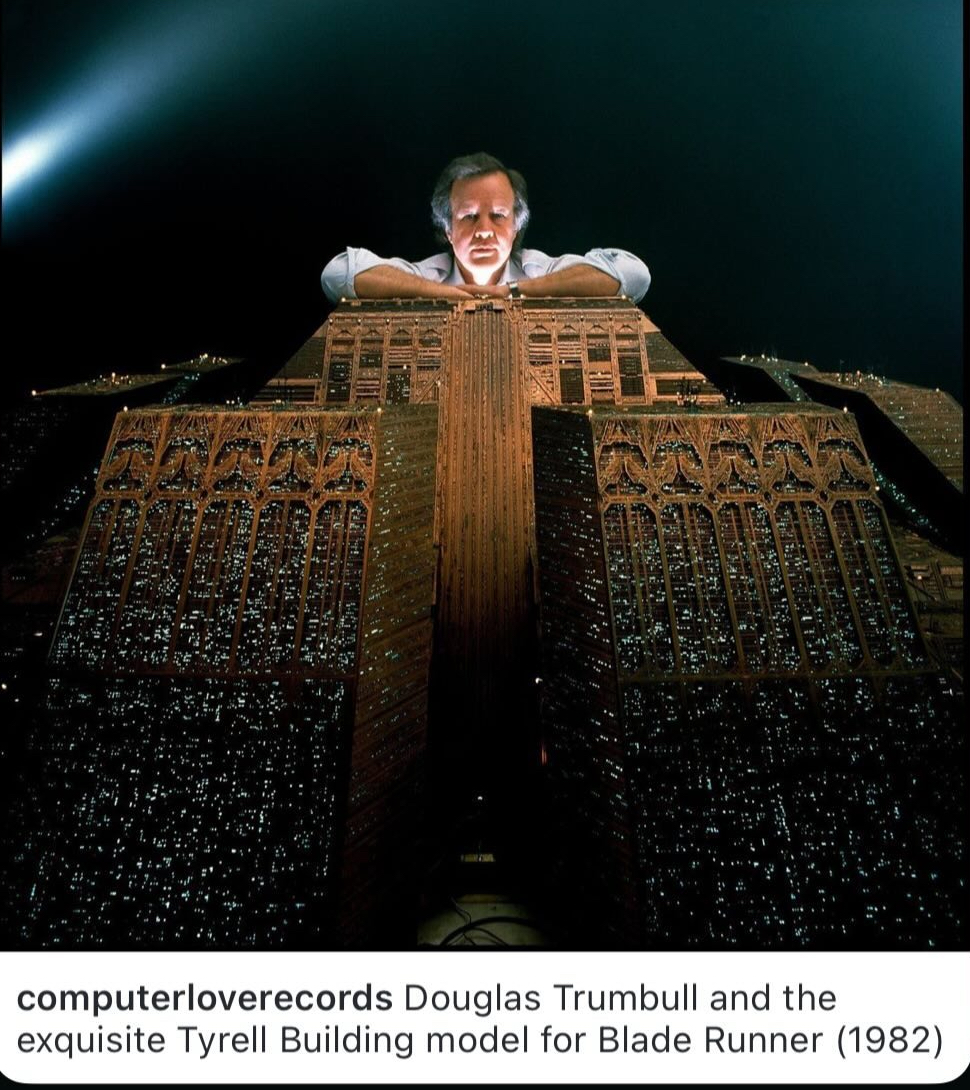

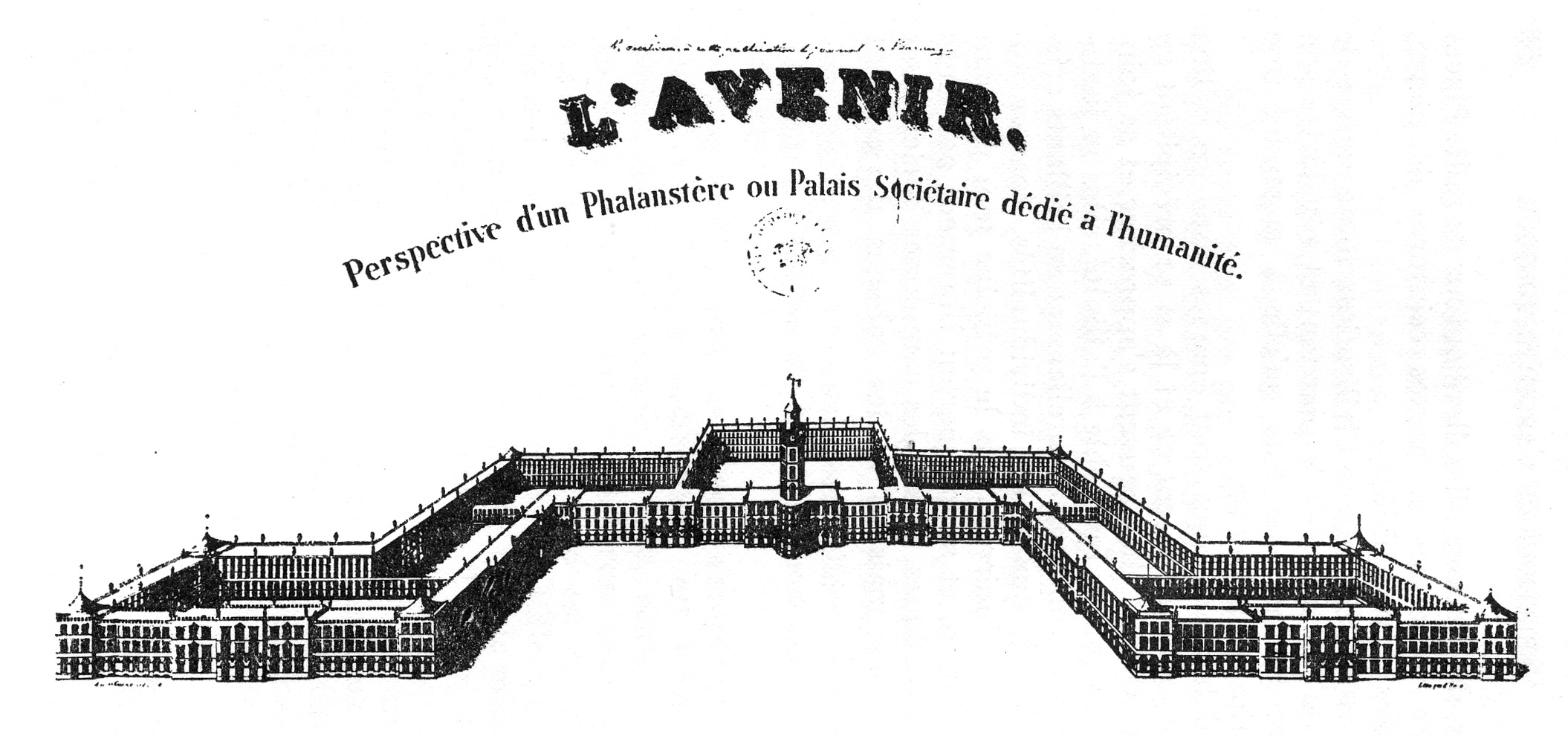

A decade earlier, Dutch situationist painter Anton “Constant” Nieuwenhuys had become fixated on the potential of visionary architecture to create infinitely configurable spaces of play, and proposed his own megastructure, “New Babylon.” Constant’s ideas were dismissed by Situationist International founder Guy Debord, who condemned the idea of a prescriptive situationist architecture. Soleri and Constant’s city reconfigurations were overshadowed by projects like Buckminster Fuller’s “Old Man River’s City” and “Triton City,” and suffered the same criticisms by association. Soleri’s forms, if not his ideas, were borrowed by science fiction media, and from there entered the language of videogames, including the city-building simulation series SimCity, which incorporated arcologies as a highly optimized version of a residential city block.

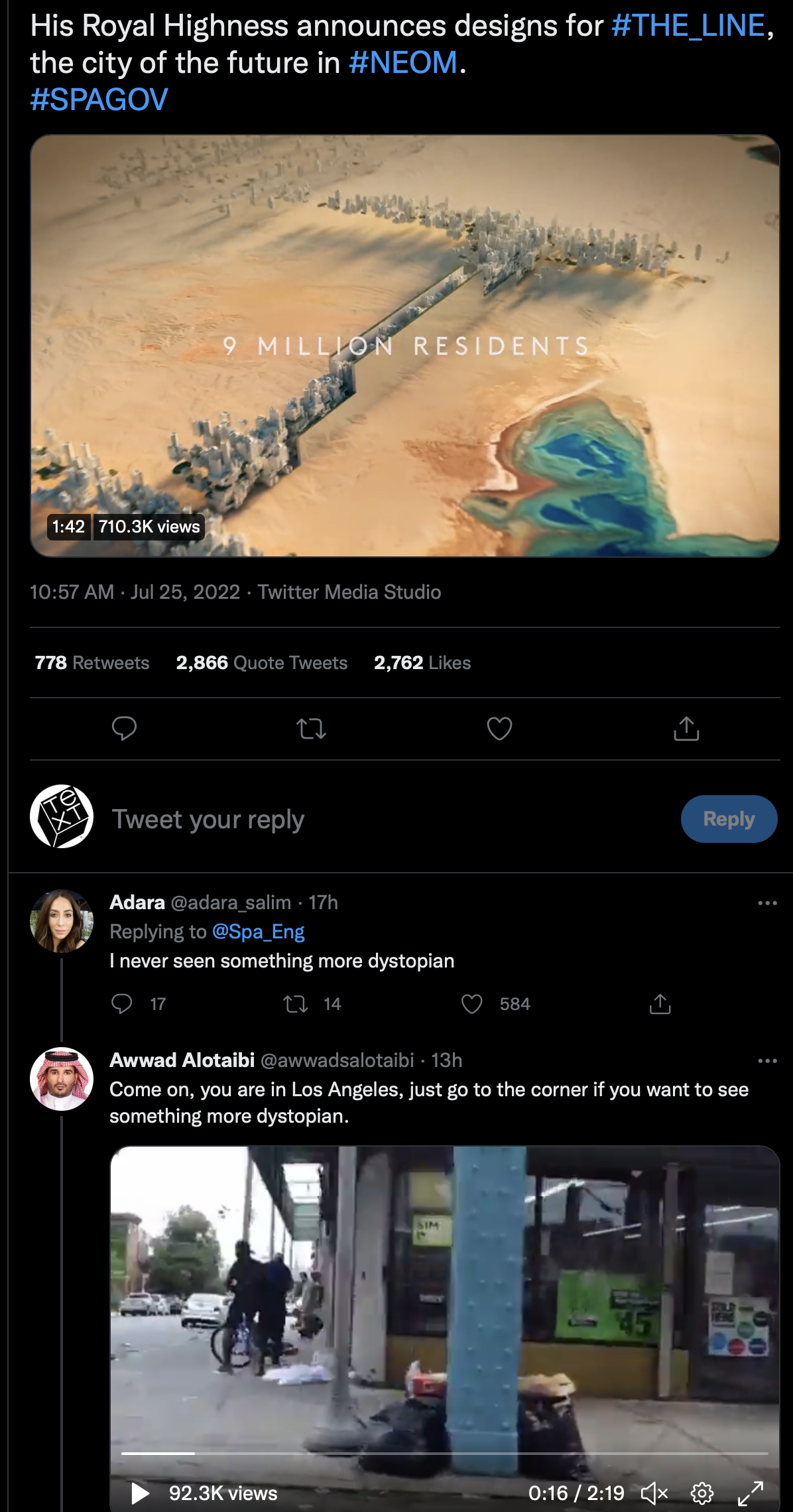

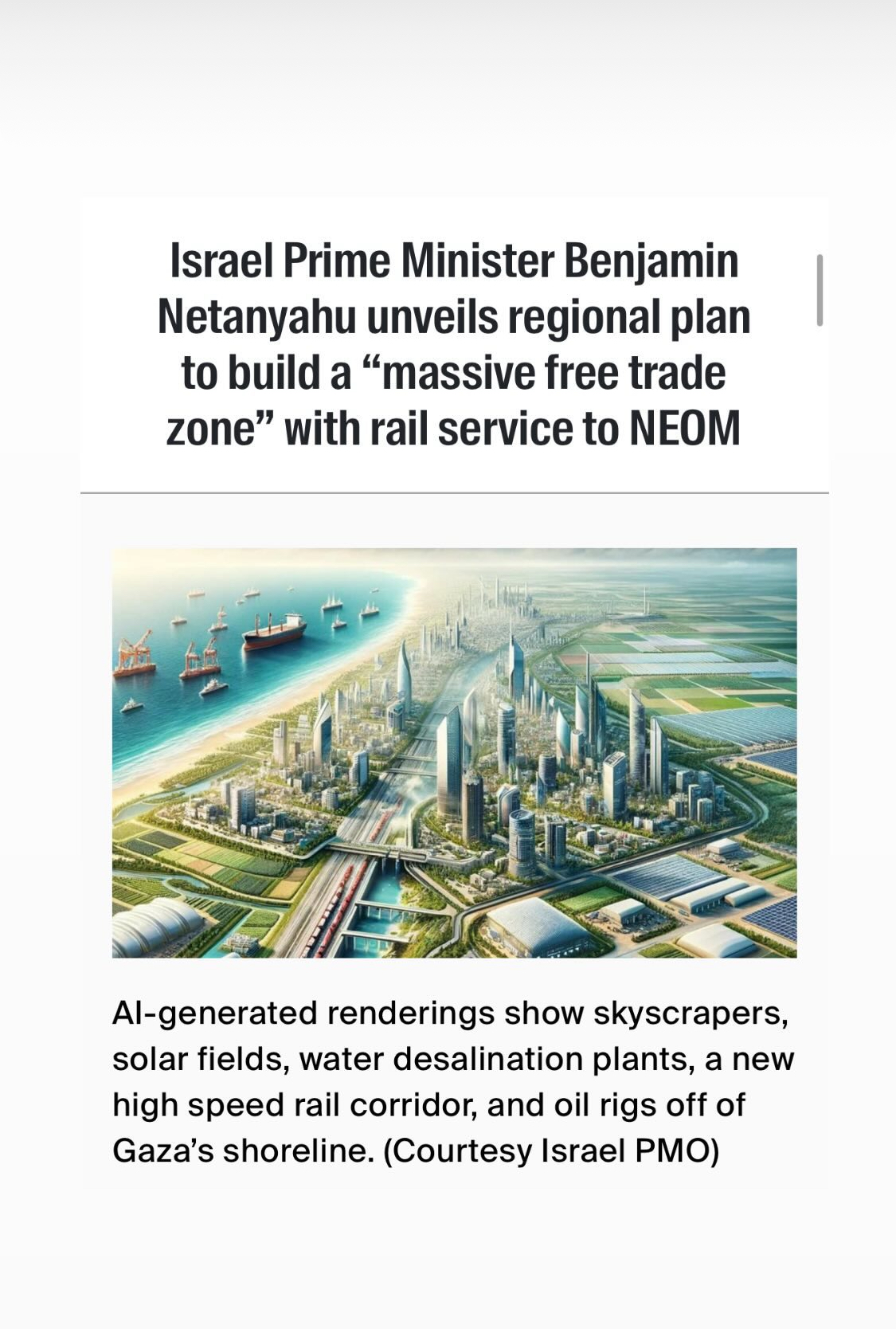

On January 10, 2021, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the authoritarian leader of Saudi Arabia, proposed his own arcology project. “The Line,” a 170 km long, mirrored, wall-like city in the desert, would obscure its own petrochemical power via calculated greenwashing. Any conception that such projects might include a reconfiguration of society, power, or the ideas of self that Soleri or Constant had, have been stripped away.

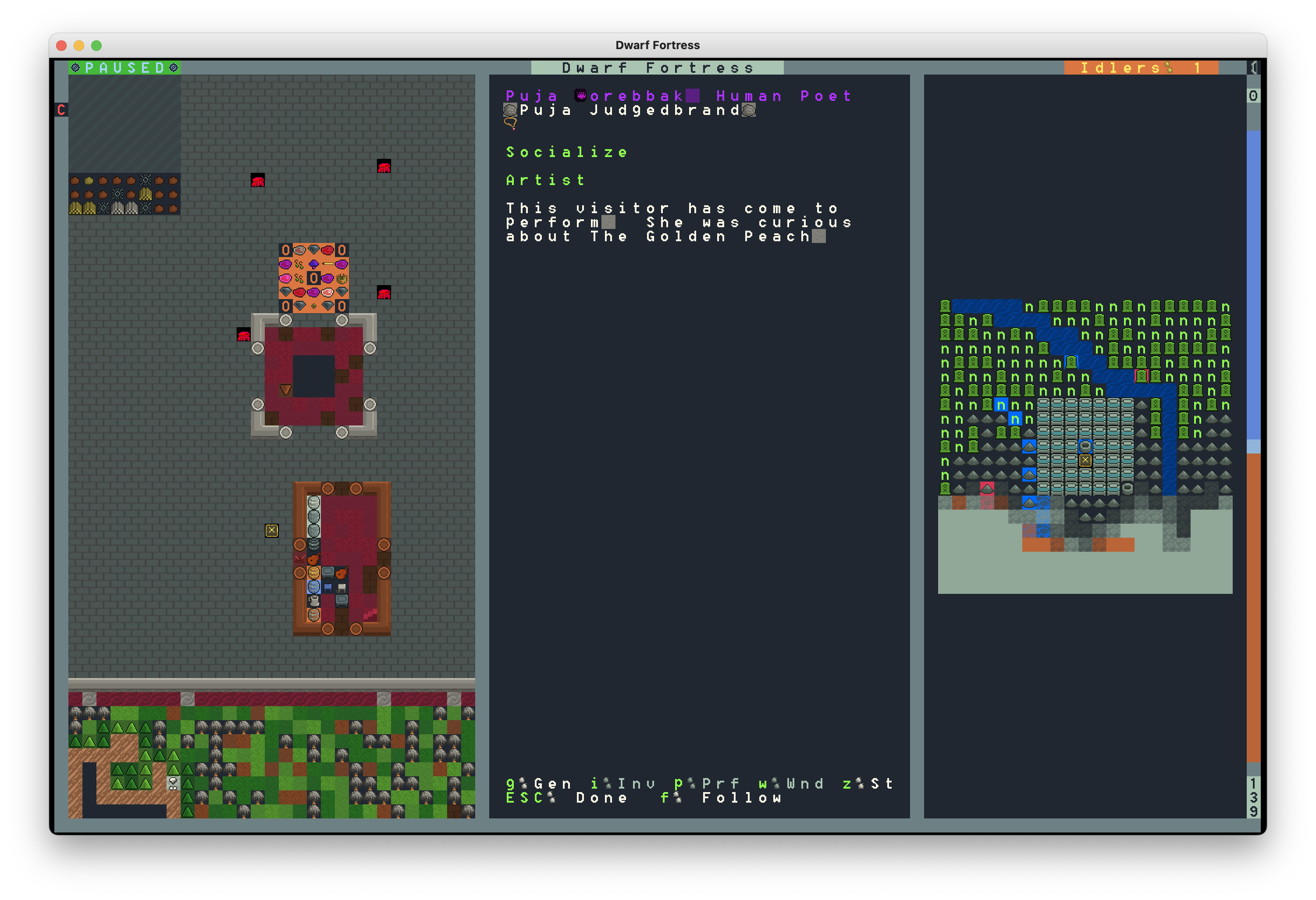

Videogames can both expertly disappear ideologies into the rules of their worlds or challenge the foundations of what we assume to be implicit. The SimCity series of games, for example, incorporates rules about which urban arrangements will be successful– moreover, reconfiguring those assumptions is not possible through gameplay. The fantasy simulation game Dwarf Fortress, however, allows for an unusual amount of freedom in reconfiguring its simulated societies of dwarves by virtue of design decisions and the unprecedented level of granularity included in its simulation. The game-self experienced by players in these two games is also very different–in the SimCity series the player acts as an unseen mayor or developer whose power over the environment is bounded only by economic resources. In Dwarf Fortress the player is similarly disembodied, but the level of agency is held in check by the will of the resident dwarves that make up the simulated society. There is no currency in Dwarf Fortress, items in the game have use-value and an exchange-value affected by the dwarves’ individual preferences and needs. Player agency in the game is limited, not by money, but rather by the individual dwarves’ wills. Exhausted, traumatized, or starving dwarves will refuse any instructions from the player, and the only concrete measure of success in the game is their happiness. Within these game worlds, the potential to reconsider implicit assumptions about power hierarchies, societal values and modes of production is tightly bound to the way we experience them through the experimentation of play.

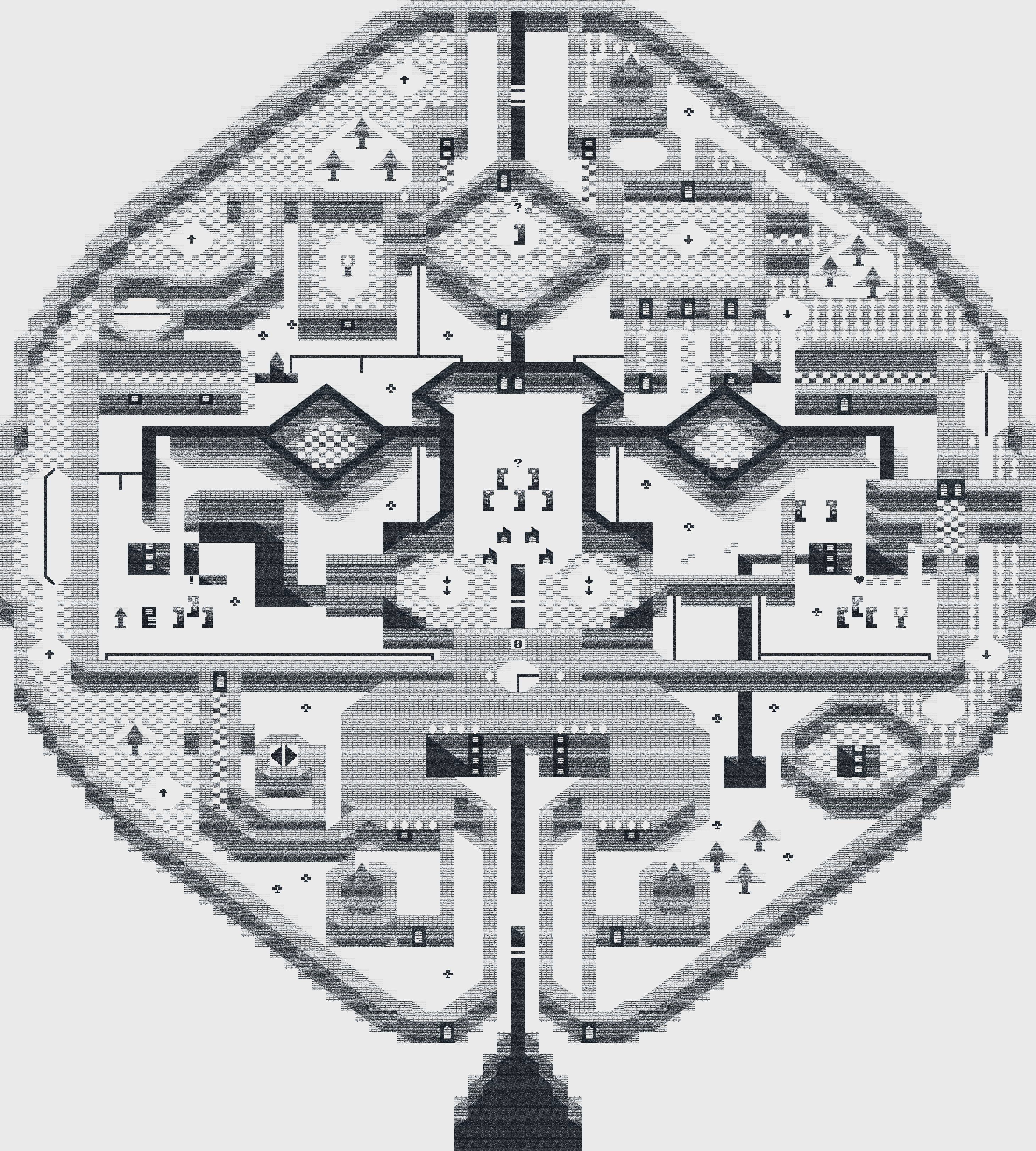

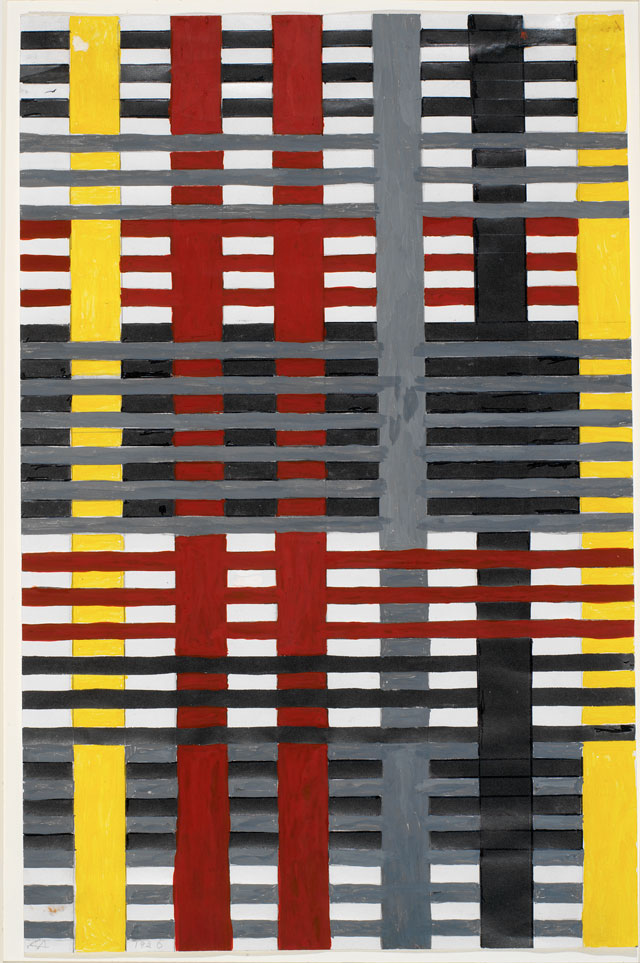

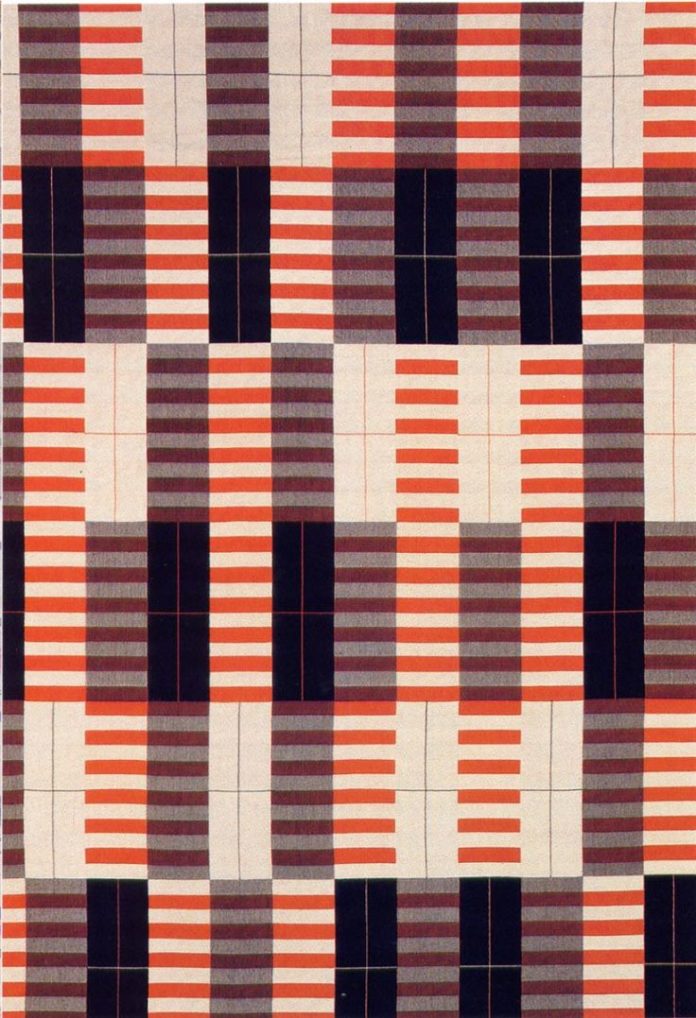

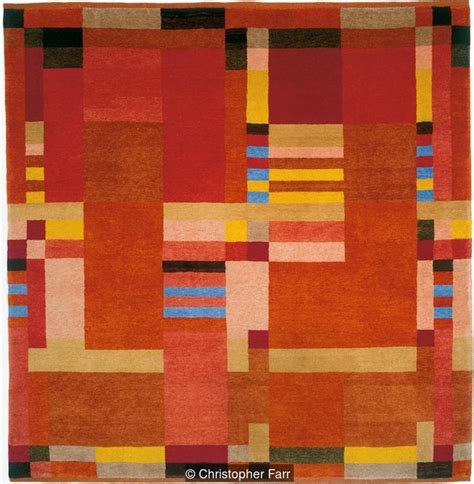

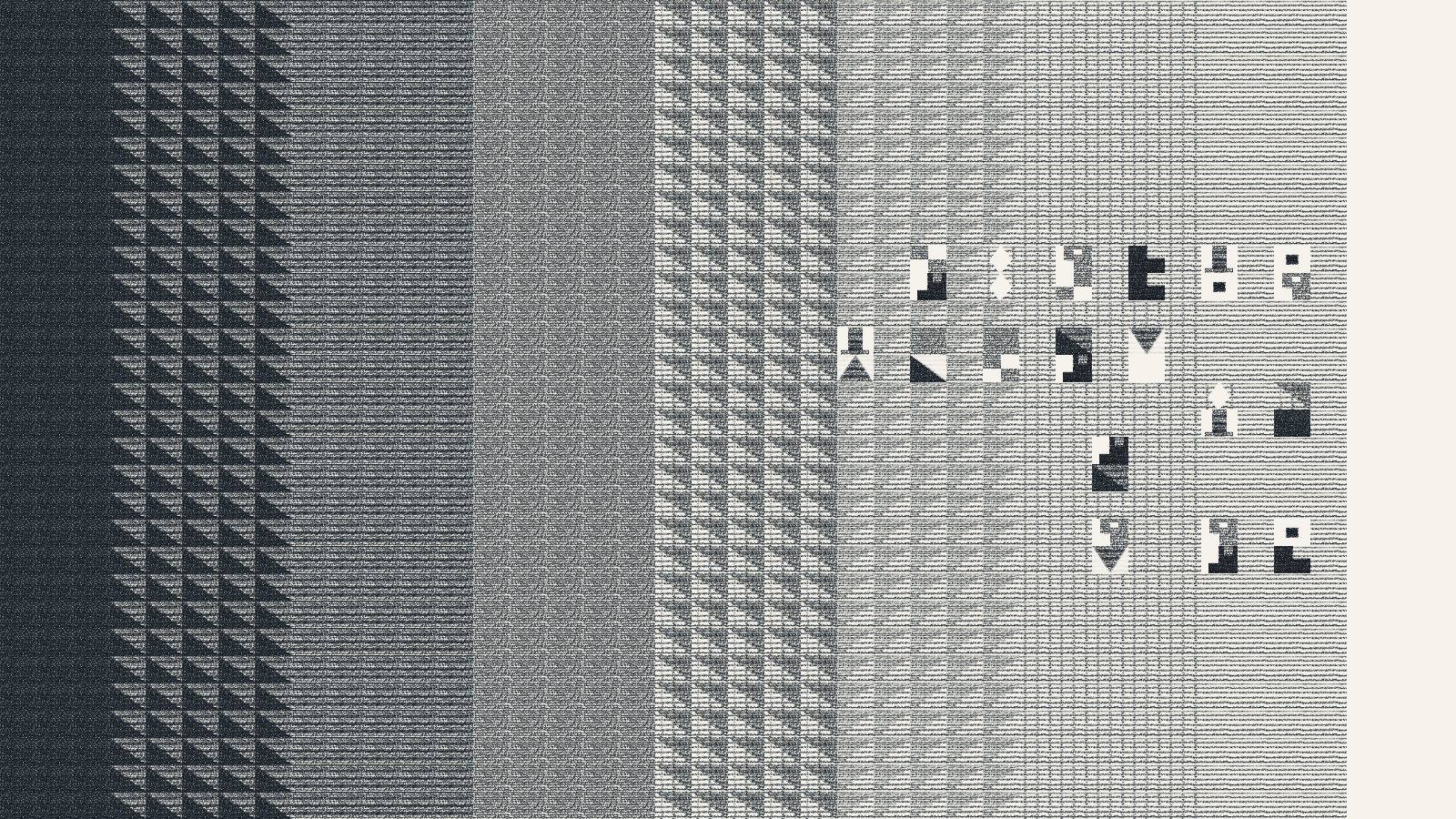

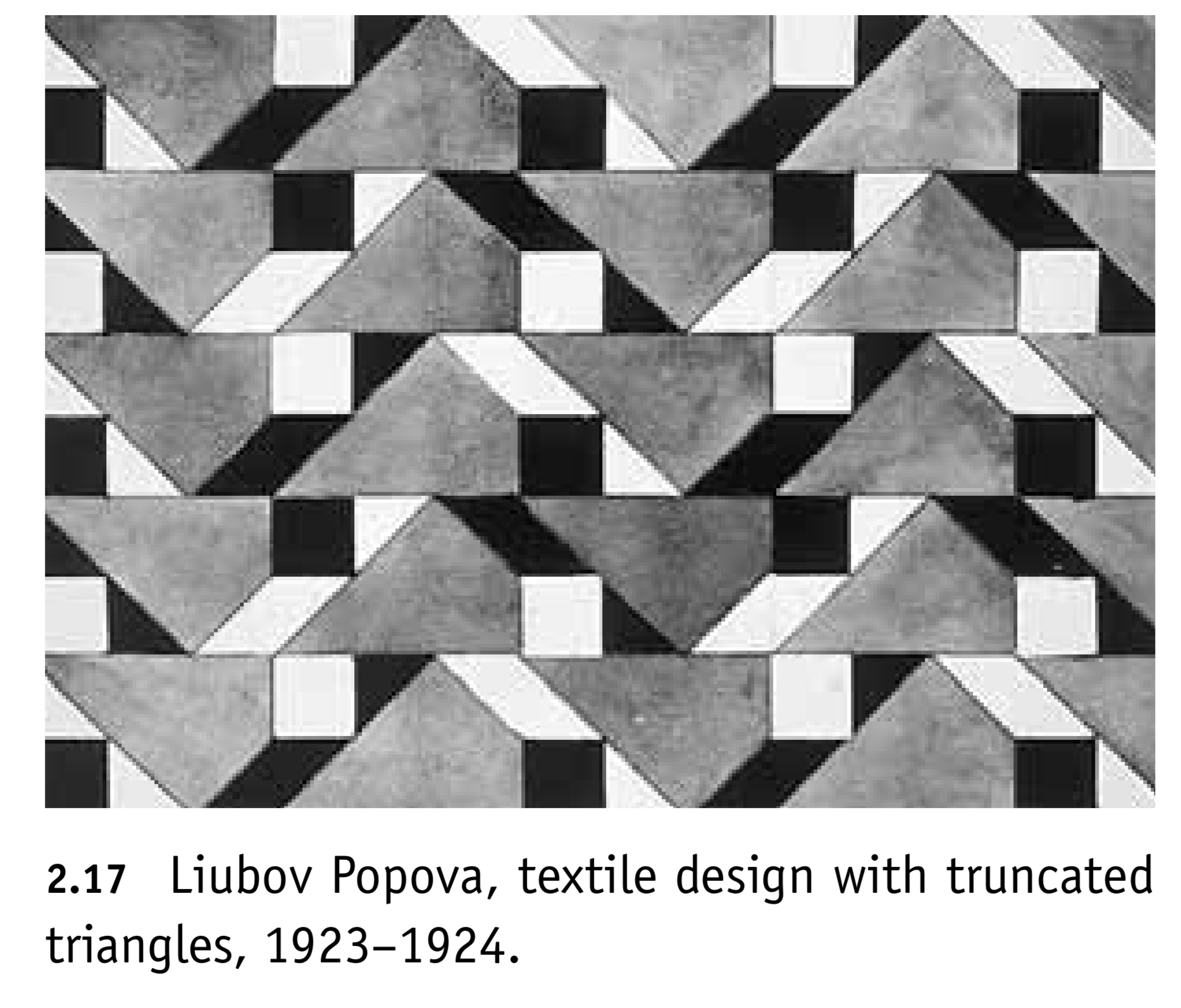

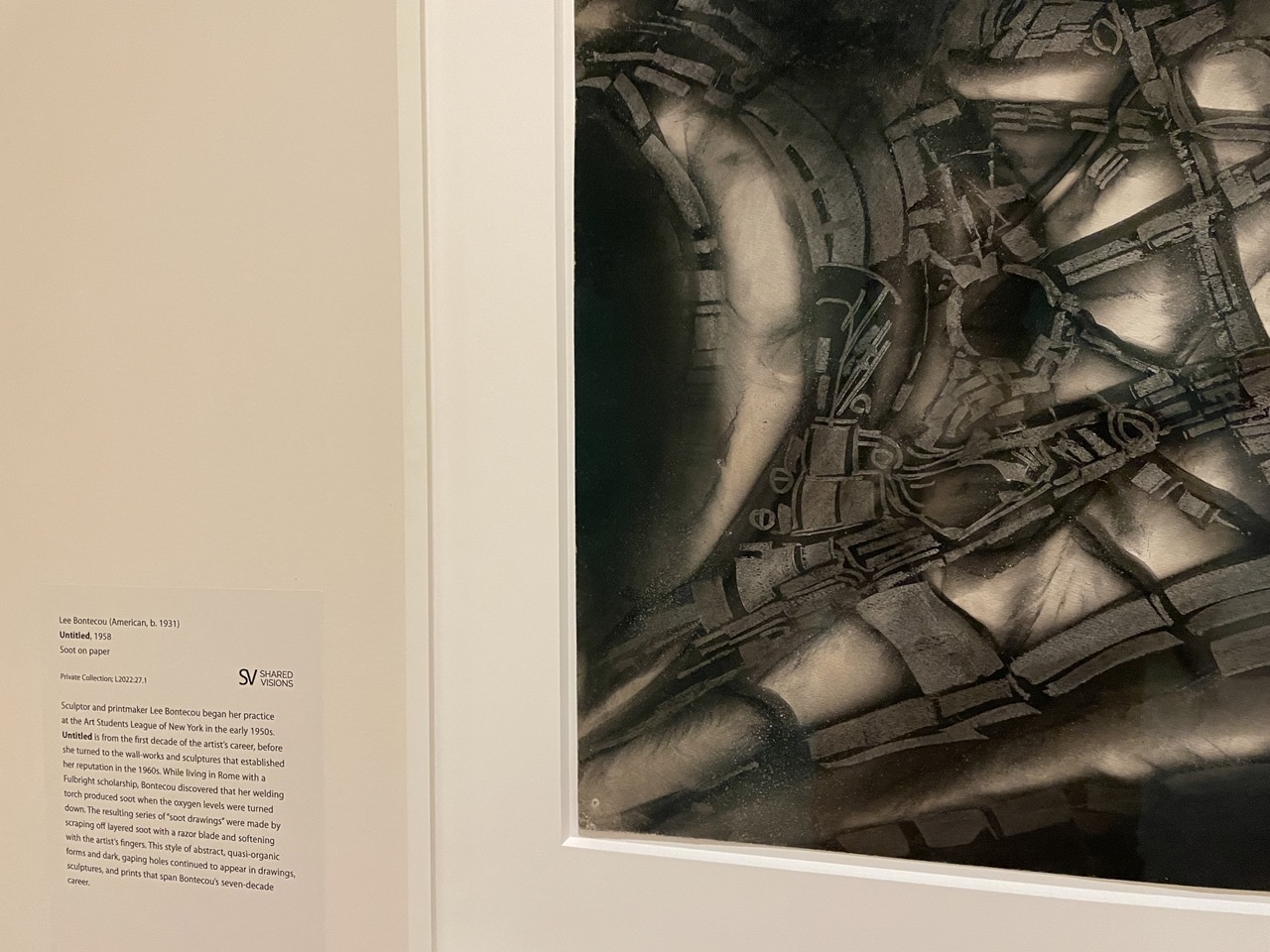

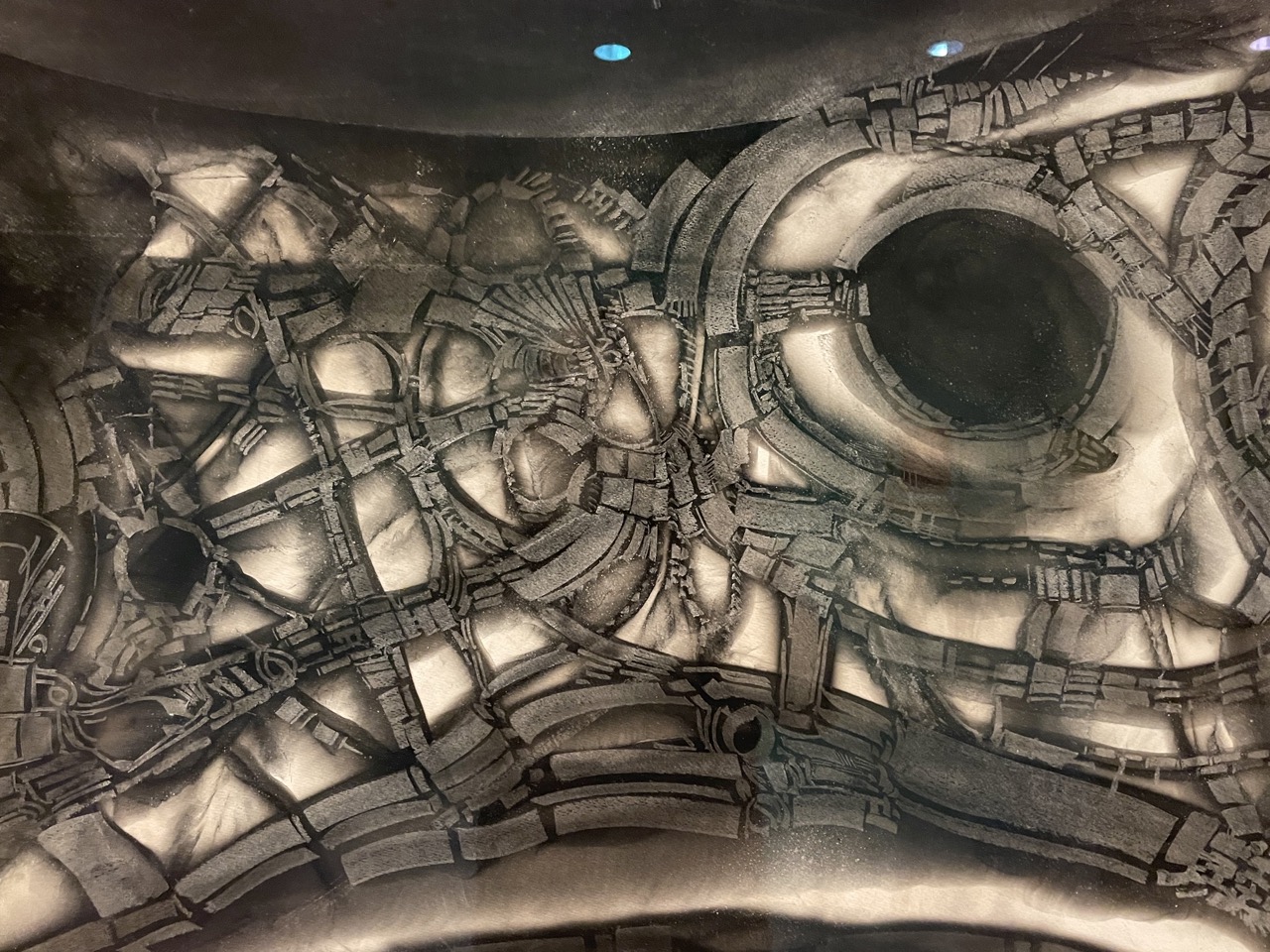

I began Archon as a space to experiment with a tile-based visual language for my thesis game project Grotto, referencing the iconic style and perspective of city simulation games like Dwarf Fortress as well as early dungeon exploration games, hand-drawn maps and textile art. I drew a collection of rectangular, reusable symbols that can be placed on a grid in combinations that suggest walls, pits, characters and other features. In some images I change or warp the perspective of the drawings. I used these tiles to draw maps of different levels and states of an imagined videogame arcology. This matrix of tiles was then modeled by a simple “wave function collapse” program, which produces a set of statistical rules for creating new images. Viewing each resulting output image, I made adjustments and created a new input image, which resulted in a slowly evolving series of map-like patterns that can be either abstract or symbolic.

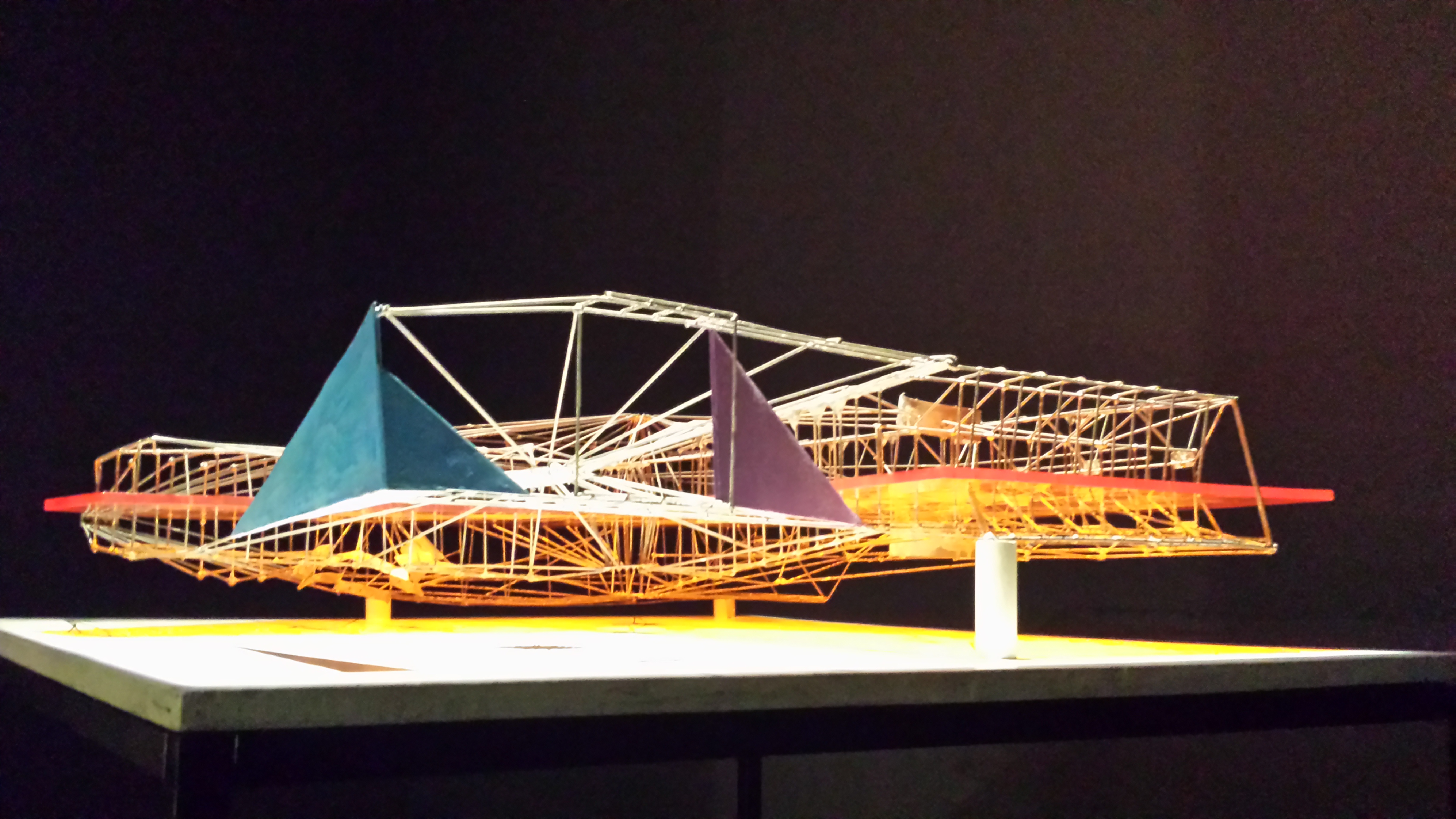

To avoid presumptions of a functioning, finished videogame that might accompany digital projections, I’ve built an anachronistic installation for Archon that houses an overhead projector and a book to showcase the images.

The name “Archon” (a Greek word meaning “ruler” that is derived from the same root as the “arch” in both architecture and hierarchy) is a reference to the power that is described in visionary architecture plans hidden beyond the edges of the blueprints and drawings. Videogames also describe power relationships, and there is potential within them to reorient us to what has been hidden or backgrounded–to rematerialize the mirage of power and plan its replacement.

Downloads:

- Archon Win32 1.0.zip, 177 MB

- Archon Mac 1.0.zip, 316mb

Repositories:

- Grotto-paint tile drawing tool (Repo may not be public)

Documents:

Videos:

Posts:

Daily Archon

I made a tumblr bot that posts pages from my Archon book with generated descriptions, intermixed with collected images of interiors.

More ➜

grids, time

Thinking some half-baked thoughts today about the grid that I’m painting on in Archon, Descartes, dualistic thought as a root of thinking of humans and nature as separate, mapping and counter-mapping, the peculiarities of the perspective of Dwarf Fortress (top down orthographic, moving down in altitude through slices of the earth but still bounded by fog of war based on what the dwarves have discovered.) How Archon let me fudge the perspective and grid in a way I couldn’t have if it was a functioning game (sometimes I show the tops of structures instead of a single layer slice, in one frame I completely explode the grid into a mess). Thinking about single player games that sit in wait for the player to be a catalyst to move npc’s into motion, something that dungeons seem to do– wait for the adventurer. How that feeds into the idea of that separation, with humans on top as primary actors. With a brain on top acting on a body. How I placed myself in the dungeon not as the adventurer, but as one of the monsters sitting in wait, playing a different game of care for a shrine. How much is Dwarf Fortress actively simulating in the deep areas still shrouded by fog of war? Thinking about the wide time simulation that happens at world gen and between fortresses, and the step by step time that happens during play.

More ➜

Grotto Tasks

Going to try to get back to logging Grotto work. Right now I am working on stuff every Saturday up until the DMA thesis show next spring. Recently we gave npc’s a flag to ‘illuminate’ if they’re carrying a candle drop, I added some icon bullets for doors to show state, and on saturday we added locked doors to stairwells and added keys. Over the last few weeks we’ve done a lot of tweaking to the auto poetry for room descriptions and I cleaned and cultivated a few new text corpuses to generate room descriptions at different depths of the dungeon. These still need to be tweaked, and I’d like to get a better handle on how the markovify functions have moved around since my original ones in order to keep making little adjustments.

More ➜

end of summer

It’s been a busy summer. Over the last couple of months I’ve written two articles, animated a music video, printed a little art book, built a big wooden projector enclosure and done a lot of work on grotto with my friend Paul (oh, and I made a barely playable twine game based on a dream I had about a horror text adventure version of Dig Dug). Right now I’m taking some of the visual work that’s going towards a future graphical version of grotto and working it into something for a fall group show at UCLA. Hopefully the two articles I wrote get published as one of them supports this work for the fall show.

More ➜

The Artist Is the Void

More ➜Supposedly, some people believe the desert is empty and others who know better reply that the desert is full of wonder. Claims of barrenness are politically useful in exploitative, extractive economies, and it’s worthwhile to examine and preempt them. […] Link Article by Elisabeth Nicula for Momus

the dungeon, the frontier, the arcology

My thesis project is about historical and future imaginaries, played out in a game substrate (a web-based game environment I call Grotto.)

More ➜

mapping

Grotto has some somewhat unique challenges to its success as an actual game because it uses an atomic maze structure where exits are blind guesses about what is inside adjoining rooms. This mode is inherited from interactive fiction, Hunt the Wumpus, MUDS, etc– games that either had puzzles within the rooms themselves, or relied on constructing a mental model of the maze based on guesses (each one potentially fatal, in the case of Wumpus). I’ve had critiques about whether the game is intelligible and whether there is any player enticement to play. I’ve kind of sidestepped these critiques by saying that the real game mechanics haven’t been implemented yet, and that they would be the sugar that activates the content I am spreading through the maze in room and item descriptions. This suggests that I have some kind of plan for game mechanics though, and all my game design ideas gravitate towards roguelike mechanics, which may not be a good fit here. A roguelike structure where a visual map is slowly completed by exploring would probably require a substantial amount of retooling.

More ➜

items, eyes, maps

Today was a first planning meeting to resume development on Grotto, and start the big project– the one I’m now calling Phantom Homeland (I got a good laugh out of calling it Dusičky for a little while, but come on).

More ➜

glyphs

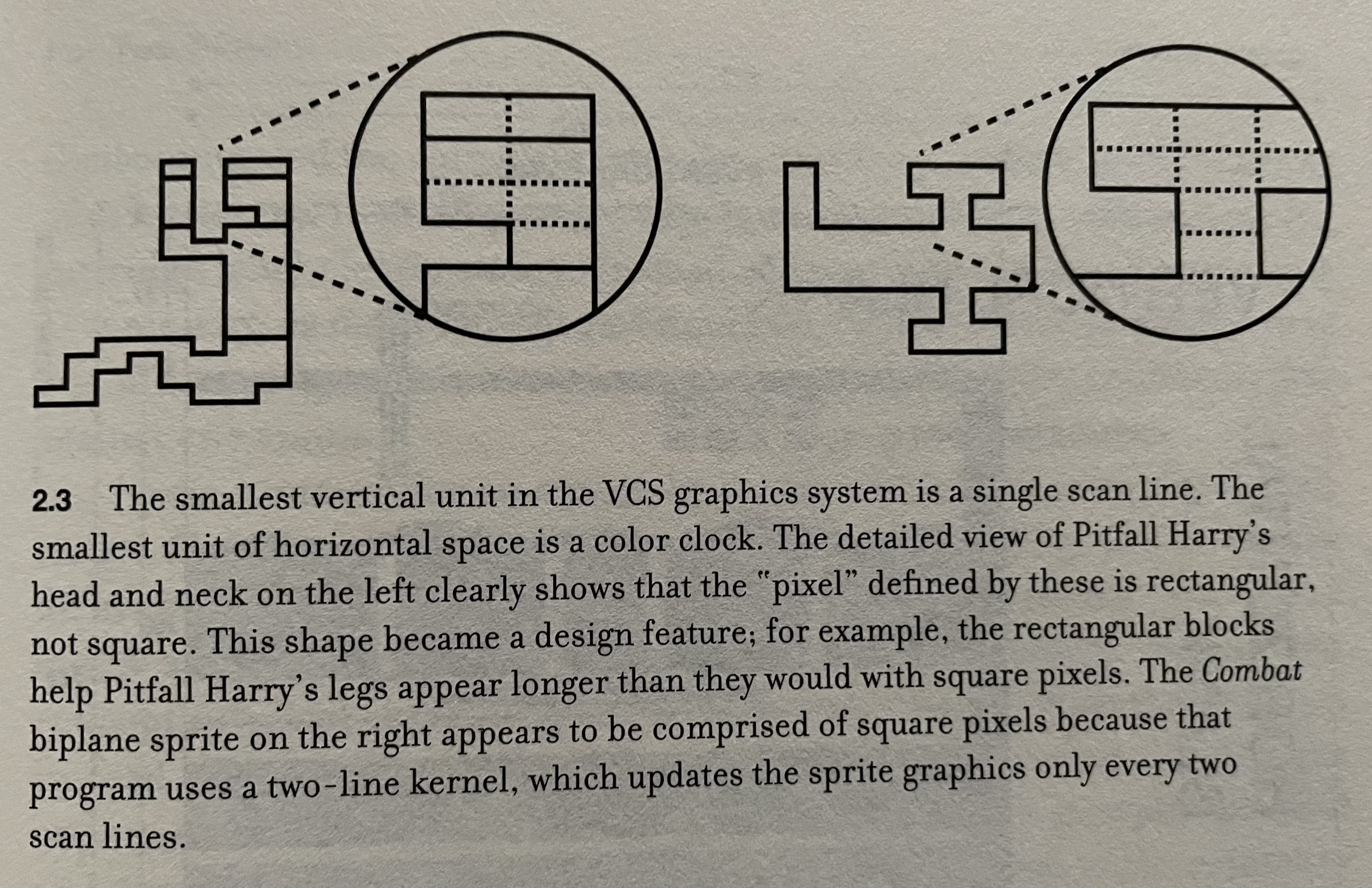

Last night I was thinking about how to evolve the gui for grotto. Specifically- taking the older text view and fusing some elements from the joystick-gui view into it. I’d like to add a div with a top down map view of the room you are in with glyphs signifying items and doors. I added some new tiles to my drawing tool and started playing with the most minimal way to represent objects. when I stopped trying hard to represent things and abstracted all the way down to two-tile glyphs, I immediately unlocked a memory- another atari game (eyeroll emoji). The creatures from imagic’s Cosmic Arc

More ➜

(1).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

(1).jpg)

.jpg)