Matriky Complete Archive

Room Collection

Tower

Depth: -1

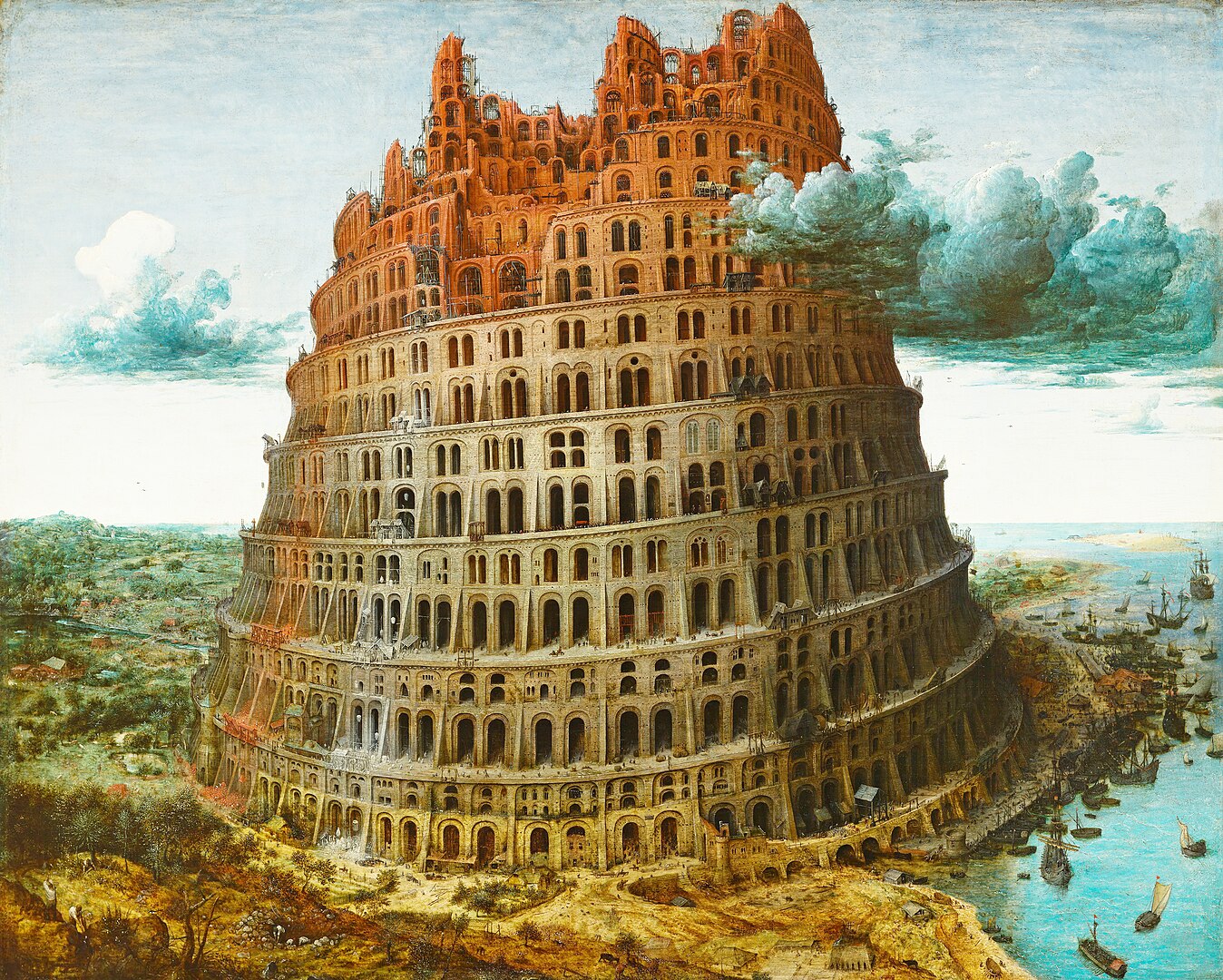

The Tower of Babel, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563

The Tower of Babel, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1563

Just as the Arcology is a fantasy of a future social arrangement reified in the built environment—one that describes, through worldbuilding, who belongs inside and who remains outside—the Tower of Babel appears in culture-building myths as the origin of difference, as if such divisions were handed down by God.

Cum filii hominum in agro Sennar post diluvium non recolentes nec mente pertractantes sponsionem factam a Deo ad Noe, patrem eorum, dicentem: „Nequaquam perdam ultra aquis diluvii omnem carnem et ponam arcum meum in nubibus celi, et erit signum federis inter me et terram“, sed pocius diffisi de Deo pre timore iterum futuri diluvii civitatem et turrim in altitudinem maximam construere niterentur; omnipotens Deus insipienciam eorum redarguens et magnificenciam sue divine potestatis ostendens in eodem loco linguas eorum divisit in LXXII ydiomata. Et inde nominata est turris eadem Babel, quod interpretatur linguarum confusio. Ibi eciam unum ydioma slouanicum, quod corrupto vocabulo slauonicum dicitur, sumpsit inicium, de quo gentes eiusdem ydiomatis Slouani sunt vocati. In lingua enim eorum slowo verbum, slowa verba dicuntur, et sic a verbo vel verbis dicti ydiomatis vocati sunt Slouani.

When the sons of men, in the plain of Shinar after the flood, neither remembering nor considering in their hearts the covenant made by God with Noah their father—when He said: “Never again will I destroy all flesh with the waters of a flood, and I will set my bow in the clouds of heaven, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and the earth”—but rather, distrusting God out of fear of another flood to come, sought to build a city and a tower of the greatest height, Almighty God, reproving their folly and showing the greatness of His divine power, in that very place divided their tongues into seventy-two languages.

And from this the same tower was named Babel, which is interpreted “confusion of tongues.” There also one tongue, the Slavic tongue—called in corrupted speech “Slavonic”—took its beginning, from which the peoples of that tongue were called Slavs. For in their language slowo means “word,” slowa means “words,” and thus, from the word or words of that tongue, they were called Slavs.

— Pulkava’s Chronica Boemorum

Closed Room

Depth: 0

Crepuscle

Depth: 0

During my time as a graduate student at UCLA, I experimented with games and hypertext as a way to spatialize scattered stories and ephemera about my family. Things that didn’t fit into easy narratives, which I wanted to spread out, arrange or bury. Over time the project grew larger and more ungainly as I started to care less about my immediate family and more about imagined identities.

Throughout the project, an advisor persistently challenged me to find what would draw players who didn’t already know me into my game. I often defensively answered that I didn’t know—or that I didn’t care, despite my belief that the game was a space that should be public and multiplayer.

During the early days of the pandemic, with an expanding awareness of multiple global crises, it felt unnatural to be concerned with what might draw tourists into my shameful crypt, or with whether the game was “fun”. In time though, I began to realize that what I had done was create a ruin. And there was a certain aspect of a ruin that seemed important to me— that it was a private space that had become public.

In the first year after I made the game, interest quickly faded. Candles and incense burned down. Monsters once killed or banished crept back into the darkened rooms. Each week I tended to the chambers representing relatives I had known, sometimes venturing farther into the halls of more distant ancestors.

I programmed bots to control characters that would in turn sweep rooms and gather scattered relics, but by 2025 their hosting platform, Glitch.com, was bought out and liquidated. Once again, I alone maintained the space. I began to think more about the infrastructure that sustained the crypt. The code lived on GitLab, the files on Amazon’s cloud. In my daily life I had joined a boycott of Amazon’s marketplace and delivery services, yet the game still relied on its servers.

I started to think about an archival version of the game. The large print-on-demand book I had made for my thesis show was only able to represent about 500 rooms out of a maze that contained over a thousand. I decided that one day I would archive the space as microfilm, like the Mormons had done with their genealogies. Devotions would continue to be carried out on a kneeling pad I created, which ticked a mechanical counter with each prostration. The microfilm would be sealed in a time capsule and lost.

Entryway

Depth: 1

I am a descendent of Moravian (present day Czechia) peasant immigrants to central Texas. My grandmother’s family primarily spoke a dialect of Czech and held on to a Czech identity, despite how culturally removed they had become from their Eastern European relations.

Throughout the cold war my family continued to receive letters from Czech relatives. At age seven, I remember the feeling of staring at a page of ruled notebook paper, unable to think of what to write to my Czech cousin Marek who had told me he was “praying for a basketball for Christmas.” My mother and I lived alone on her preschool teacher’s income but I had no conception that we might be “poor”. At this age I was obsessed with acquiring a computer, and did not understand that this was then out of the question financially— in fact I assumed it could happen at any time. The letters from Eastern Europe were full of pathos to me and I found myself unable to think of anything to write back.

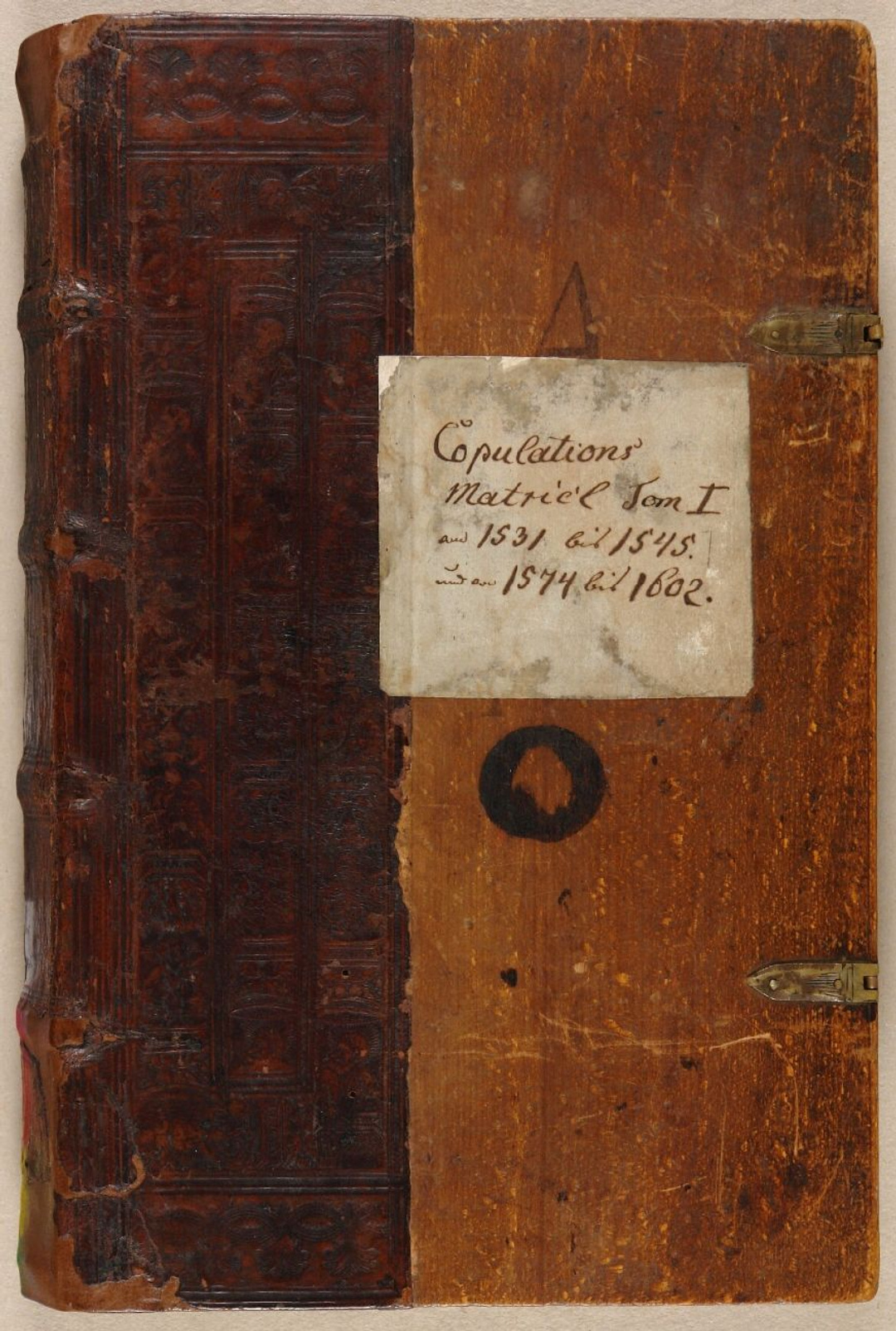

In winter of 2023, I found myself combing through the online historical archives of Czech towns. I painstakingly tried to read scanned pages from a Moravian Parish book dated 1807 during one long night. Looking for the Pavel of “Pavel” and the Frydl of “Fridel” among the pages, the looping lines of tight Kurrent script teetered past the edge of forming sounds in my mind before dissolving into voiceless chicken-scratch. 1 I was trying to find a marriage record between Pavel, my great-great-great-great grandfather, and someone who might have been named Veronika Chrasteka…

Abyss Edge

Depth: 1

Once I started researching, I quickly came up against a point in my genealogy that there were names without concrete records, only conflicting data added to the website Ancestry.com by distant relatives that my mother calls “the bad cousins.” 2 According to their account, Veronika Chrasteka gave birth to my great-great-great grandfather Valentine sometime in her fifties, so the veracity of their records is somewhat in question. They do also claim that Pavel and Veronika married in 1807, presumably in their village of Halenkov, so that was at least a place to start looking for records. This required learning something about Matriky, or Parish books, church registries kept in bureaucratic detail to keep track of Czech peasantry. 2

Forest

Depth: 2

The command to be biologically productive orients us to ascend through an imagined homogenous time, but in the labyrinth each moment contains every past moment, growing outward like rings as the past echoes internally like video feedback.

Billy Burkhalter, great-grandchild of Dionysius, threw his voice into the forest, to the delight and confusion of all the children. Was it Billy speaking or was it the forest? Whose voice is here?

The dungeon built from data asserts its own authority and solidity, but relics, carried by players through the maze of Grotto, provide slippages and portals from one time and person to another. Ahmed continues to play with the connotations of words in describing a sort of queer pathfinding that cuts through the assertion of straight genealogical hallways—

Queer orientations are those that put within reach bodies that have been made unreachable by the lines of conventional genealogy. Queer orientations might be those that don’t line up, which by seeing the world “slantwise” allow other objects to come into view. It is no accident that queer orientations have been described by Foucault and others as orientations that follow a diagonal line, which cut across “slantwise” the vertical and horizontal lines of conventional genealogy, perhaps even challenging the “becoming vertical” of ordinary perception. [@ahmedQueerPhenomenologyOrientations2006]

Akenson reminds us that genealogies are narratives that serve cultural desires. In the case of cultures that emphasize patrilineal lines, they may even be fictional narratives, as paternity can only be established for certain very recently. In the case of the Latter Day Saints, the narrative of genealogy follows a very strict grammar. It’s a patriarchal structuring of humanity that disappears social arrangements that don’t fit within it. While Ahmed’s work focuses on the ways in which queer experiences are excluded from dominant cultural narratives, Akenson’s book explores how family histories are often constructed to support preconceived notions about identity and heritage.

In stepping through the architecture of my family dungeon, I located rooms that corresponded to two of my mother’s cousins. The Burkhalter brothers were two gay boys, one of whom was an amateur ventriloquist (who amazed the family children by throwing his voice into the nearby woods). Their father was physically abusive and dominated their immediate family. My mother remembers the time her Aunt broke down the Burkhalters’ door and struck the father in defense of the boys, throwing the house into turmoil. The genealogy data that I have access to gives me only the driest impression of them— that they lived and died, one young. It doesn’t tell me that one of the brothers died by his own hand, just that he served in the Korean-American War. It tells me that the surviving brother married, had children and divorced. It’s only through a surprisingly candid obituary that I can see that the longest-lived of the two brothers came out as a gay man late in life, and his funeral was attended by his partner of many years. “I remember at a family funeral he came up to me, smiling,” my mother said of her cousin, “and he took my hand and asked, ‘Sheryll, have you had a good life?’ ” Reading a name from the obituary, I inscribe a room in the database for this partner, and a relic traces a slantwise path between the pair. 3

Sinkhole

Depth: 2

I’m spending the holidays in my home town of Austin, Texas. It’s a city that is cyclically purged of successive populations born to it– currently by rising rents and property taxes. The Austin airport is filled with functioning museum-versions of restaurants that have been forced out of business in the city itself, and live on only as simulacra valued for the residual branding they offer the city. I’m old enough that I’ve seen several waves of people pushed out of the city along with their businesses and arts venues, so it’s hard to get angry about it now. I only feel a sort of dim, directionless displacement here. With friends and relatives scattered and having been in Los Angeles a few years for school, I don’t really feel at home anywhere.

In the next few days we are anticipating a cold snap that brings back memories of the winter storm that hit Texas in 2021, which resulted in a massive, prolonged power outage and a handful of deaths from exposure and smoke inhalation. The state is assuring us that the power grid will withstand the usage surge this year, but this promise may hinge on the voluntary actions of Texas’ massive infestation of parasitic cryptocurrency miners, who were paid by the state’s energy provider ERCOT to reduce their energy consumption during this summer’s heatwave [@chiuLimitingCryptoHelped2022]. Texas is both a site of fossil fuel extraction and of energy wastes that flow from that extraction, a symbol of entrenched petrochemical power with a puppet state government that seems to exist primarily to serve that power. I’m staying with my elderly mother who lives in a small, somewhat dilapidated house in northwest Austin surrounded by two-story luxury homes that have sprung up around it. The other houses seem embarrassed of hers, waiting for her departure so that the plot of valuable property can be liquidated. The home was a HUD foreclosure that she and her father purchased for $32k after her divorce in 1988. In Austin’s current housing market the property is probably worth twenty-five times that now. Her faucets leak, the roof over the porch-slab slumps. “You’re sitting on a gold-mine,” one of our townie relatives tells her with an edge of urgency.

The house may be a little run down, but it is a house, and it’s no small thing that we had it when I was growing up, her father was a WWII vet who moved up in class from a wilderness subsistence farmer to a skilled laborer after being trained in construction during his time in the Navy and then benefiting from the G.I. Bill. He was able to step in when we needed help. In the years that followed WWII, G.I. Bill benefits were notoriously earmarked as white-only, creating a compounding disparity in multigenerational wealth between white and minoritized soldier’s descendants. The promise of upward mobility, now dwindling for anyone in the working class, was often predicated on its exclusions.

My mother lives frugally off of social security and sporadic small checks she receives because of her share in the mineral rights from a family farm. My family on my grandmother’s side were Moravian immigrants to Texas who arrived here after the civil war. They worked as laborers and then managed a plot of farmland in the town of Kurten Texas for a hundred years. After the last generation of our family living on the farm died or were moved to assisted living, their heirs (including my mother) parceled the land out and sold it after years of disagreements. While the property held little residential value (electricity had been connected but there was a well and an outhouse rather than plumbing) or value as modern farmland, the farm became valuable instead for the trickle of oil that had been found on it sometime in the 90’s. The mineral rights and revenue stream from the haphazard spurts of oil were divvied up among the families, who drifted further apart. I think sometimes about how many generations of family lived together and worked the land on that farm. Certainly I would have found a life there stifling, but I wonder about how the land and its history was traded away for abstract value. But again, we were lucky– while some could sell their land, others simply had it taken away, or their rights to it delegitimized. -12/21/2022

Airbell

Depth: 2

I have a mental image of something I never witnessed but now know occurred— my mother cleaning the “mud room” of my grandparents’ house after her step-father’s suicide (the room where his locked roll-top writing desk sat), sparing her half-sisters and mother the experience. I think about how she grew up in that family as the remnant of her mother’s previous marriage. The details of her parents divorce seemed sordid— my grandmother had carried on an affair and left my biological grandfather Milton for his foreman Bob at the construction firm he worked for. As a result my grandmother had ascended in class—but the costs to her were high. In early 1950’s Texas, adultery was a criminal matter. My mother remembers the police being involved when my grandmother’s affair was discovered. My grandmother was a practicing Catholic as well, and the subsequent divorce and remarriage resulted in her being denied communion for decades. This is the context my mother pulled into the act of scrubbing the mudroom floor, and it informs how she was oriented towards that space.

I have a mental image of something I never witnessed but now know occurred— my mother cleaning the “mud room” of my grandparents’ house after her step-father’s suicide (the room where his locked roll-top writing desk sat), sparing her half-sisters and mother the experience. I think about how she grew up in that family as the remnant of her mother’s previous marriage. The details of her parents divorce seemed sordid— my grandmother had carried on an affair and left my biological grandfather Milton for his foreman Bob at the construction firm he worked for. As a result my grandmother had ascended in class—but the costs to her were high. In early 1950’s Texas, adultery was a criminal matter. My mother remembers the police being involved when my grandmother’s affair was discovered. My grandmother was a practicing Catholic as well, and the subsequent divorce and remarriage resulted in her being denied communion for decades. This is the context my mother pulled into the act of scrubbing the mudroom floor, and it informs how she was oriented towards that space.

Threshold

Depth: 3

Assimilation was a lengthy process that was not completed until my grandmother Dorothy’s generation.

Dorothy on the farm, dressed in contrast to her mother and aunt

Dorothy on the farm, dressed in contrast to her mother and aunt

Red Room

Depth: 3

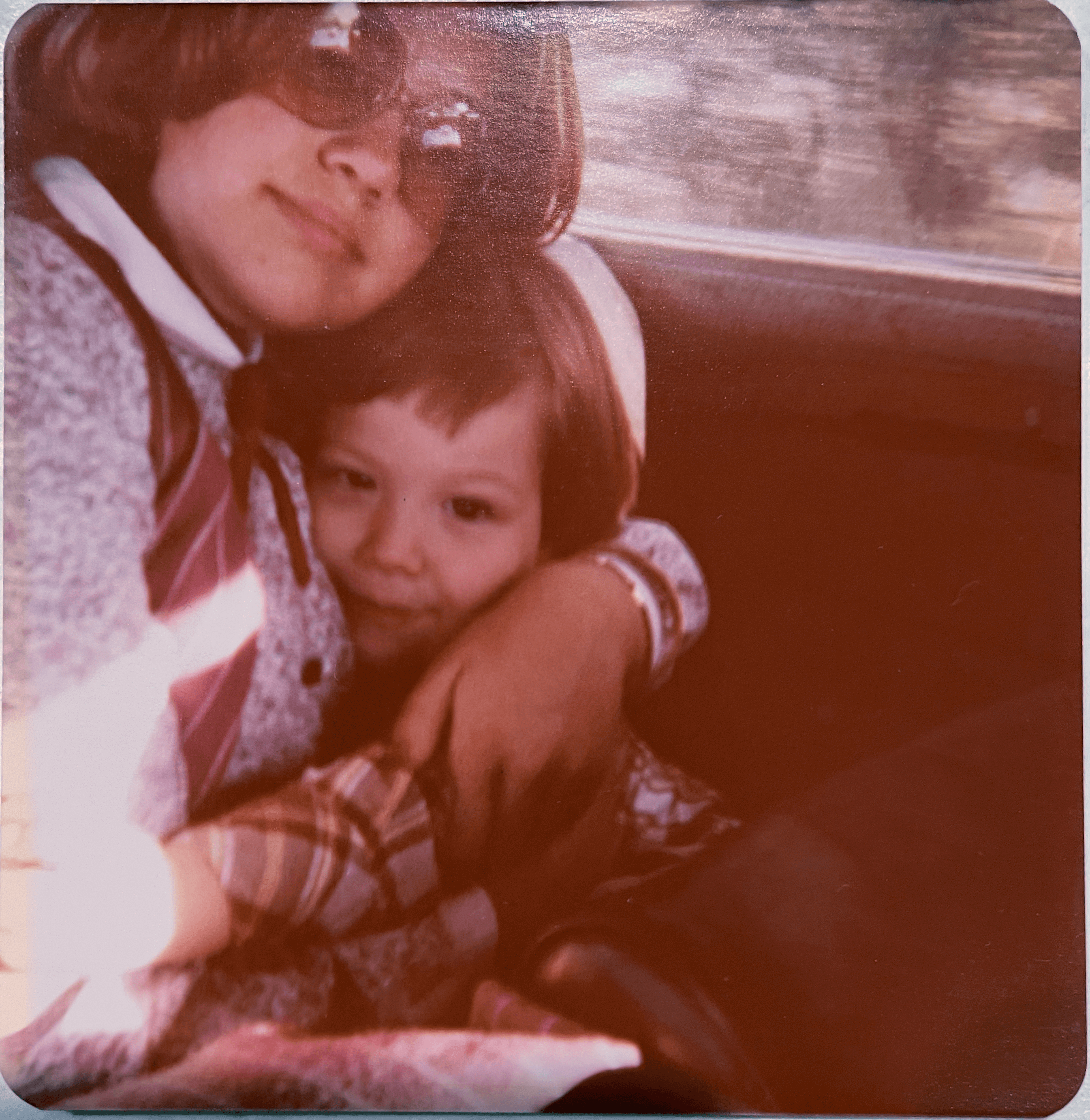

Returning from Red’s funeral with my half-sister, the second funeral I had attended, one Mormon, one Catholic. Two religions in which baptism is a form of data entry into vast archives

Returning from Red’s funeral with my half-sister, the second funeral I had attended, one Mormon, one Catholic. Two religions in which baptism is a form of data entry into vast archives

I had three grandfathers. I never knew my paternal grandfather, Jack “Red” Wiggins, who died when I was small. He had left my father’s family, and then when he was 60, he converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS, or informally by outsiders “The Mormon Church”) in order to marry a younger mormon widow. My only memory of Red was attending his funeral as a toddler. He lay in his casket in Mormon burial garments, my family and I stood out as the only strangers among the rest of the attendees. My father says he has blocked the experience out.

Esther White Room

Depth: 3

I can hear you tapping softly outside the guest room door, in the hall, measured, hoisting the sun into position beyond the green lake and gray misty scrub. When you chime the mourning doves shiver and sigh at your calling. Barefoot, I walk across the still-dark carpeted floor of the room and lay my ear over the door. You know something I don’t know, so much of this house that you built is still dark. My feet try to know as much as they can, the too-clean carpet, linoleum, wood, red dust, sticker burrs, the acid kisses of fire-ants, thick grass of spring, the soft muck of the lakeshore, the peeling paint and baked wood of the dock. Like everything else, in time this place will be for sale. You’ve made sure you can pay for a funeral that never seems to arrive. Everything must go. What will you do with all this? Should I get rid of these memories? Where will you put my ashes? You know something I don’t know. The sun rises in this direction, or is it that we rush towards it? If I unlocked its chest I could not hold it, I would slip away into its monstrous light. Slip away if I were to try to carry it from the root cellar to the lake. That sightless space, were it to become day, would turn from something unknowable into something meaningless—the beating of a deep mass of daddy-longlegs bodies against concrete. A soft tapping of a heart outside of the guest room door. A tiny soft foot learning to be pierced and stung.

Mine

Depth: 3

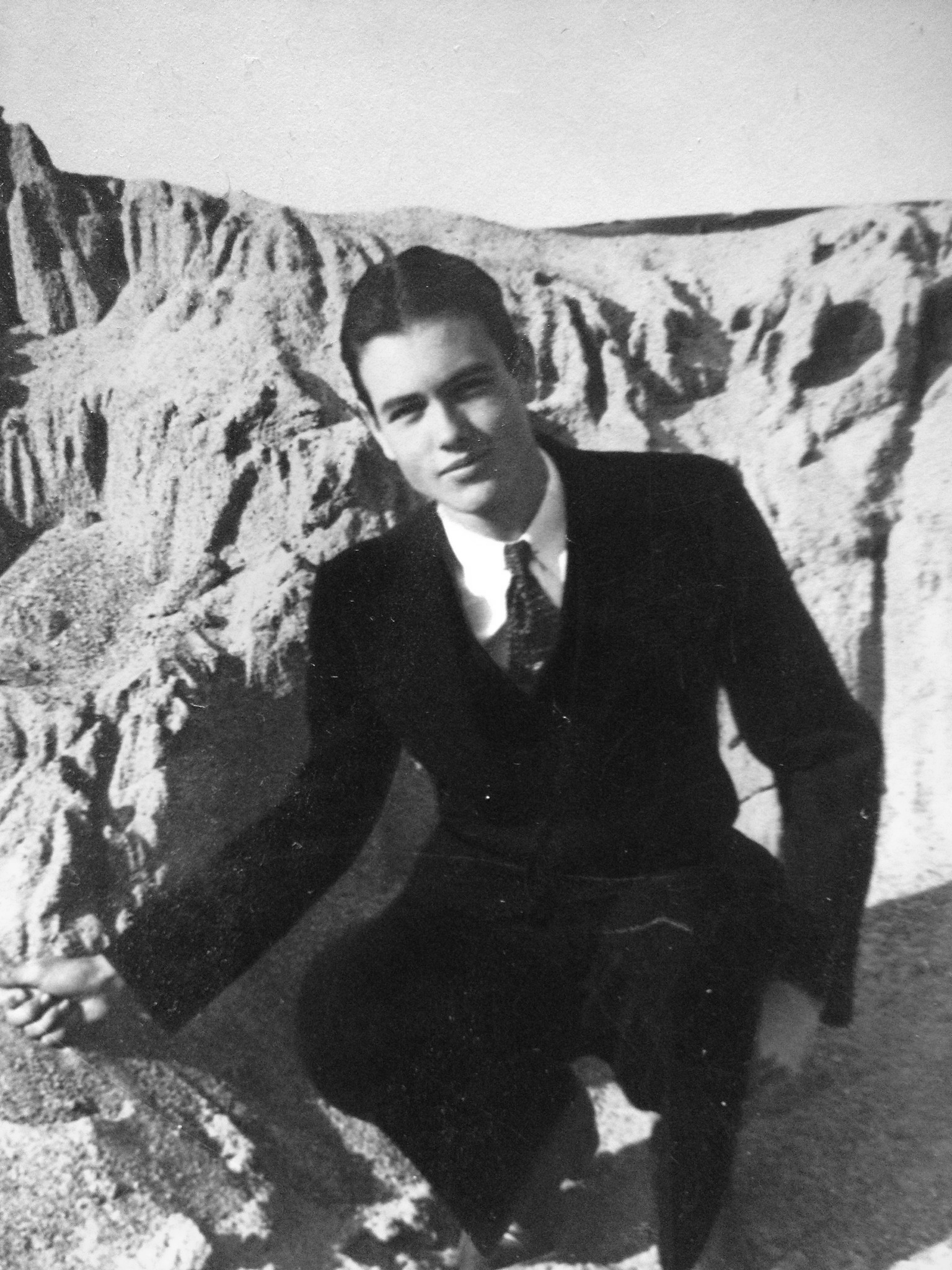

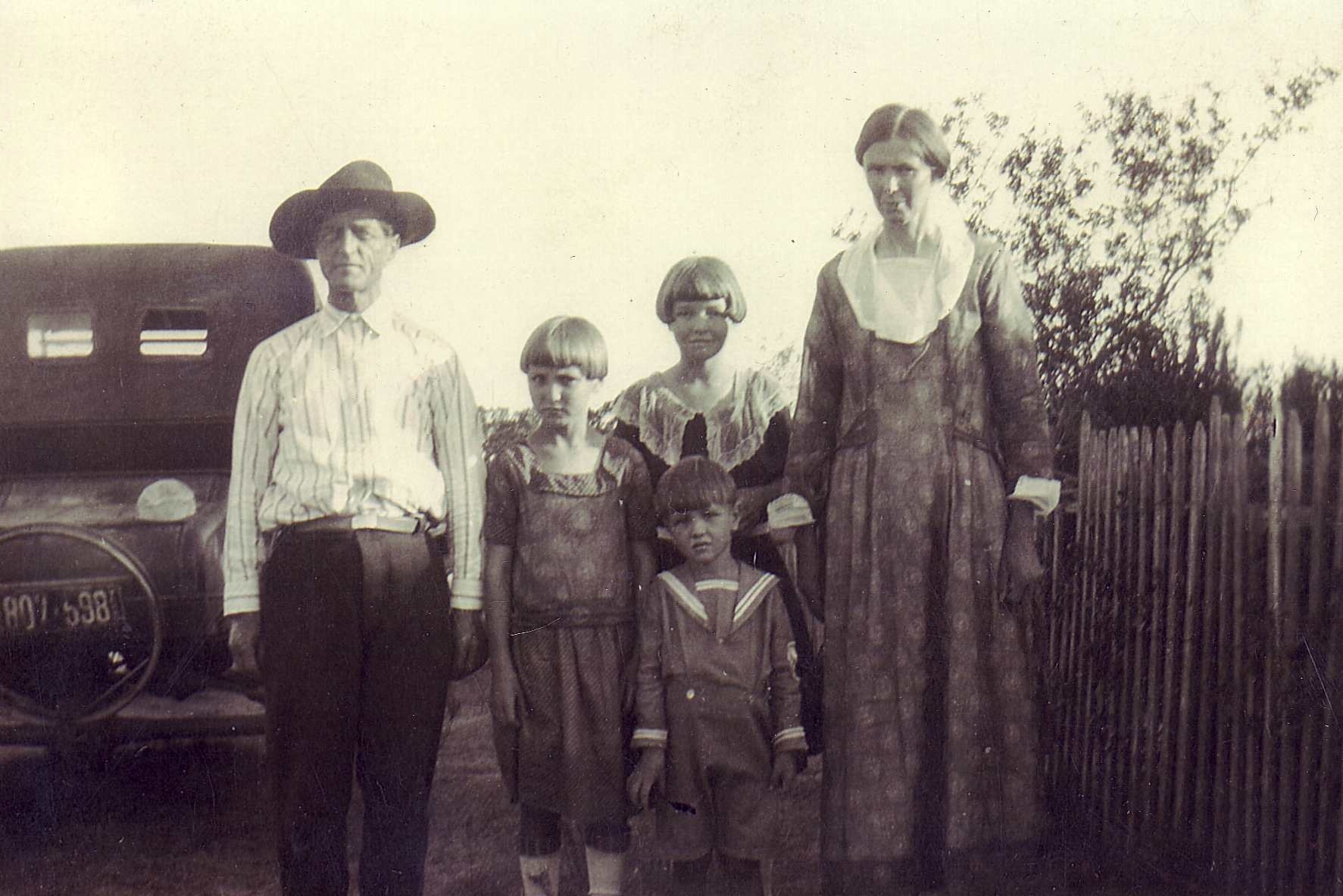

Peter Fridel and family in Ennis, Texas

Peter Fridel and family in Ennis, Texas

The story goes that a […] miner, unwilling to believe that the pit he worked had been exhausted, moved with his family into the mine after it was closed. There he doggedly searched for a new seam. Eventually he found one, and other miners join him to build a subterranean, utopian Coal Town— an autonomous underworld environment, artificially lighted and ventilated and capable of supporting human life in complete independence from the surface world.

[@williams2008notes]

Mud Room

Depth: 3

In both my aunt and uncle’s home and my grandparents’ home, videogames became a sort of extra-domestic space—a crack in a wall that could be passed through to a variable architecture that was connected to and dependent on the ‘real’ house. In both homes there were good reasons to keep children inhabiting their own separate space. My uncle, who struggled with alcoholism, later took his own life. When I was eight years old, my grandfather Bob shot himself in the room where the Atari was kept. After being diagnosed with bone cancer, his employer had terminated his health insurance coverage. That room was called the “mud room” in my family. It was a transitional space between indoors and outdoors—a place where muddy boots were quarantined, paperwork was done (in a locked roll-top desk) and where children played. It was also a transitional space from the home into the places accessed via the game console. It was also a transitional space from life to the hidden space of death.

Shortly after my grandfather’s death I remember one day of being back in the (now cleaned and emptied) mud room playing another Atari game, Sneak n’ Peek (1982). In my mind it was another dungeon, mapped on the iconography of a family home. The videogame is a version of Hide and Seek, where hiding places (invisible, enterable pockets of space) riddle a house. The visible topology of the environment must be tested (by slowly moving the stick-figure-like player character into each pixel) in order to find the location of hiding places. Two children could take turns hiding and testing the skein of the house for invisible folds. One child playing alone could only search for a computer player over and over. As a child playing alone, it was never your turn to hide. I imagined that this was because the computer already knew where everything was hidden.

Just as the house in Sneak n’ Peek had permeable walls, the Atari was a portal to other spaces in my grandparents’ home. Somewhere beyond the closed door of the mud room, adults were planning my grandfather’s funeral.

“Thank God for Pac-Man,” I remember my grandmother saying through a closed door.

Temple

Depth: 3

The tenets of the LDS Church are too intricate and, over time, too variable to delve into detail here, but, like many other worldbuilding projects that attempt to fix an identity to a mythological “origin,” they have historically fallen into traps of biological and racial essentialism, extrapolating supposed biblical cues into a convoluted narrative that positioned northern Europeans as being the inherently “superior” descendents of the Israelites. 4 They are not unique among religions in this tendency, joining a long list of various chosen peoples. We are interested in them here because they are a worldbuilding project that begins at the dawn of modernity, positions itself as an “American” religion, and which is actively engaged with both computer technology and history. Nineteenth century Mormons also believed that First Nations tribes were their distant cousins— descendents of Israelite tribes who had become dark-skinned due to sin. This resulted in some disappointment when Mormon-baptized indigenous peoples did not magically become light-skinned after being submersed [@akensonFamilyMormonsHow2007, 27].

Spanish Conquistadores also thought that indigenous people must be Hebrews:

Also popular was the idea that the peoples of the New World were descendants of the lost tribes of Israelites. Or, perhaps, of Jewish exiles from Rome, evidence of which was the finely wrought golden jewelry found in the Yucatán. “We can almost positively affirm,” wrote Father Durán, that Mexicans “are Jews and Hebrews.” Almost positively. Fernando de Montesinos spent years in Peru producing five dense manuscript volumes reading New World history through the book of Revelation, arguing, among other things, that the Andes were the site of King Solomon’s fabled mines. The Spanish destruction of the Inka Empire, then, wasn’t so much a conquest as a rediscovery and reestablishment of Israel of old. Since, according to Christian esoterica, a new Jerusalem had to be raised and Jews converted to Christ before the Apocalypse could begin, the Conquest was a necessary step in the fulfillment of prophecy, and thus legal. 5 [@grandinAmericaAmericaNew]

From Some Family—

From 1976 (when the mission-to-the-dead was declared to be scripture) to the present day is a new temporal page in Mormon genealogical work. The present-day, well-informed “Saint” probably would be surprised and embarrassed to learn the nature of what was held to be divine truth only a generation or two ago. At an official level (whatever folk-beliefs may be), the LDS church today (1) no longer literalizes the descent of individual members from Ephraim. A new “Saint,” in receiving a tribal identity in the patriarchal blessing, now is merely being assigned a tribal identity by adoption, not the definition of his or her literal lineage;12 (2) the implicit “British Israelism” – the idea of the Anglo-Saxons and the Nordic Europeans being flush with the blood of the Lost Tribes of Israel – has been quietly dropped;13 (3) the bar to black priesthood was removed by divine revelation vouchsafed to the First Presidency in 1978; (4) the LDS church has tried to get along better with Jews (in, for example, stopping its baptizing of Holocaust victims), but there is a limit here to how far the “Saints” can go. After all, they still see themselves as being the truest (albeit not the only) form of the real Israel; (5) and, the idea that there is a connection between whiteness of skin and closeness to the Almighty, which had made for difficult relations with “brown” New World populations – the “Lamanites” – now is not much talked about. However, in the mission fields of Latin and South America, it still is useful to tell potential converts that they are descended from the ancient Israelites. And particularly in Polynesia, where the indigenous cultures maintain long and highly prized genealogies, the literal belief in brown peoples’ being part of an Israelite group can be tied into each indigenous culture’s origin-myth. [@akensonFamilyMormonsHow2007, 223]

archive

Depth: 4

Property—in the private or state realm—simply could not function as a set of societal relations without archives. W. E. B. Du Bois in his 1920 essay “The Souls of White Folk” noted that “whiteness is the ownership of the earth forever and ever, Amen!” Archives are both the invocation and the benediction to possession and dispossession. The earth, its lands, and its bodies could not be owned if they could not be inscribed. If archives provide the answer to Du Bois’s prayer, for nonwhite peoples they represent the angel of death. It is at the moment of death, when the blood no longer pumps through the body, that archives accomplish their most practical purpose in capitalist societies: to proscribe the transfer of property, as outlined above, across generations (inherit ←→ disinherit). Bloodlines and documentary proof thereof dictate the legitimacy of claims made on the materials—the land, the bodies, the archives left in one’s wake. The will, the inventory, and other probate records survive from centuries ago not simply as a result of their historical value but due to their integral role in authenticating whiteness.

[@drakeBloodRootpdf2021]

Kinship is, of course, a preoccupation of anthropologists and has been for decades. Rather than simply a substitute for the word family, kinship refers to the structural, systemic, and symbolic elements of the relationships shared among people who identify as kin, whether that be on the basis of blood, obligation, or a mixture of both (Fox 1967). The earliest social science studies of kinship emerged in the British mold of social anthropology, based on observations of so-called primitive societies (e.g., Evans-Pritchard 1940, Radcliffe-Brown 1952, Fortes 1953), mostly on the African continent, where political and kinship structures intertwined in ways inconsistent with the bureaucratic apparatus of Europe and the United States. The anthropological study of kinship has been critiqued by many scholars within and beyond the discipline, chief among them David Schneider. Schneider argued that the anthropological approach to kinship relied on an unstated assumption that “blood is thicker than water.” He called this assumption part of the “ethnoepistemology of European culture” (1984, 175) and concluded that anthropologists must confront this tacit assumption or abandon the study of kinship altogether. Schneider’s argument can be extrapolated to archival praxis. In the U.S., Drake contends, the field has likewise assumed that the family is the primary social entity around which to collect, arrange, and describe records. Archival practice in the United States, he writes, “has a family fetish evident through three avenues”: the founding of archival institutions, the composition of their user base, and the technological infrastructure that serves that base.

[@drakeGraveyardsExclusionArchives2019]

The dominant archival standards—like EAC-CPF, which encodes “corporate bodies, persons, and families”—inscribe the family as a stable and natural entity, a fiction that rarely holds true for those who have had to reforge kinship under conditions of enslavement, imprisonment or forced migration [@drakeGraveyardsExclusionArchives2019]. 6

The rights that accompany membership in a family suggest a secondary role of archives in the United States: the cultivation of a citizenry. Archives keep, among other sets of records, the constitutions, the declarations, and the laws that govern a democratic society. The accessibility of the archive, so the argument goes, reflects the fact that citizens can contest grievances on the basis of documents stored within. People have indeed used archives to hold governments accountable for abuse, detention, and other forms of violence. Yet the profession’s rhetoric—repeated by organizations such as the Society of American Archivists—casts archives as “linchpins of a democratic and thus legitimate state.” Without them, it is said, citizens become mere subjects, incapable of holding power to account.

[@drakeGraveyardsExclusionArchives2019]

In his address to the Society of American Archivists, “Secrecy, Archives and the Public Interest,” Howard Zinn argues that the notion of archivists as neutral custodians of records is untenable. He observes that archival work—collection, preservation, access—is deeply shaped by the distribution of wealth and power, meaning that those who dominate society (governments, corporations, the military) also dominate the archive. Zinn contends that when archivists claim neutrality, they in fact support the status quo: the “existing social order” is perpetuated simply by doing the job “within the priorities and directions set by the dominant forces of society.” [@zinnSecrecyArchivesPublic] Secrecy, selective access, and bias in what is collected ensure that archives protect the powerful by obscuring the ordinary lives and struggles of the less powerful. Zinn’s argument is thus that archivists should see their role not as passive stewards but as active participants in a democratic project: challenging secrecy, expanding what is collected, and attending to the voices ordinarily excluded from the record. Drake echos this, calling for a “liberatory memory work,” (After Chandre Gould and Verne Harris) in place of professionalized archival work.

Cavern

Depth: 4

My fascination with my Czech family stems from the fact that when I was growing up, my mother and I often went to visit my great-aunts and uncle on the farm in Kurten. They still spoke a Moravian dialect of Czech, and they still used an outhouse and a well for water. They produced almost all of their own food, even though everyone living on the property was of advanced age. They were a “pocket-dimension” somehow outside of modernity that I was connected to. At some point in my grandmother Dorothy’s life, she had been willing to do anything to leave the family farm and assimilate into anglo Texan culture, and from her departure, I exist.

My interest in the family’s origins started with a sheaf of shaky, handwritten notes, tracking a genealogy of the Fridel’s flight from Moravia after the Battle of Hradec Králové, during the Austro-Prussian war. The family genealogy abruptly ended just two generations before their trans-atlantic migration. Tracing it back further meant decyphering church parish books and learning about anachronistic naming conventions. 7 This kind of work offers up interesting treasures— it follows a thread into an impossible tangle that shows how meaningless and temporal the group affiliations that are sketched onto humanity are. Identites that seem real in the moment dissolve in the caustic medium of wide time.

Crucible

Depth: 4

The Greer family, between 1920-1950

The Greer family, between 1920-1950

Tunnel

Depth: 4

“You remeber that witchy shit grandma used to do?

When it would rain she would open the window and cut the rain with shears.”

Great Hall

Depth: 5

The Bryan Daily Eagle, Bryan, Texas, Friday, December 28, 1956

Rosary Held Tonight For V. J. Fridel

Valentine J. Fridel, 91, died Thursday at 5:40 in a local hospital. He was born in Moravia Aug. 8, 1865, but came to the United States with his parents when a lad of four years and had lived in the Kurten community for 87 years engaged in the farming industry.

The Rosary will be recited tonight at 7:30 p. m. in the chapel of Hillier Funeral Home by the Rev. Tim Valenta. The same priest will conduct a short prayer service in the chapel Saturday at 9:45 a. m. and also the Requiem High Mass at 10 o’clock in St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. Interment will be made in Mount Calvary cemetery by the side of his late wife who died in 1947.

Six nephews will serve as pallbearers.

Eight daughters and two sons survive him: Mrs. Lena Regmund, Mrs. Verna Hahn and Miss Annie Fridel of Bryan; Misses Bernadette, Victoria and Josephine Fridel of Kurten; Miss Mary Fridel. Mount Belvue, Miss Frances Fridel of St. Louis, Mo.; Antone and Frank Fridel of Kurten. One sister, Mrs. Mary Krohn, of North Zulch: one brother, Peter Fridel of Ennis; five grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren are the other survivors.

The Field

Depth: 5

Fridel family members working their potato field in Kurten, Texas (date unknown) 8

Fridel family members working their potato field in Kurten, Texas (date unknown) 8

In the fields my aunts wore long sleeves, bonnets, gloves, so that their skin wouldn’t tan, marking them as laborers when they went into town— but the heat outdoors in Texas, even in spring and fall, could be unbearable.

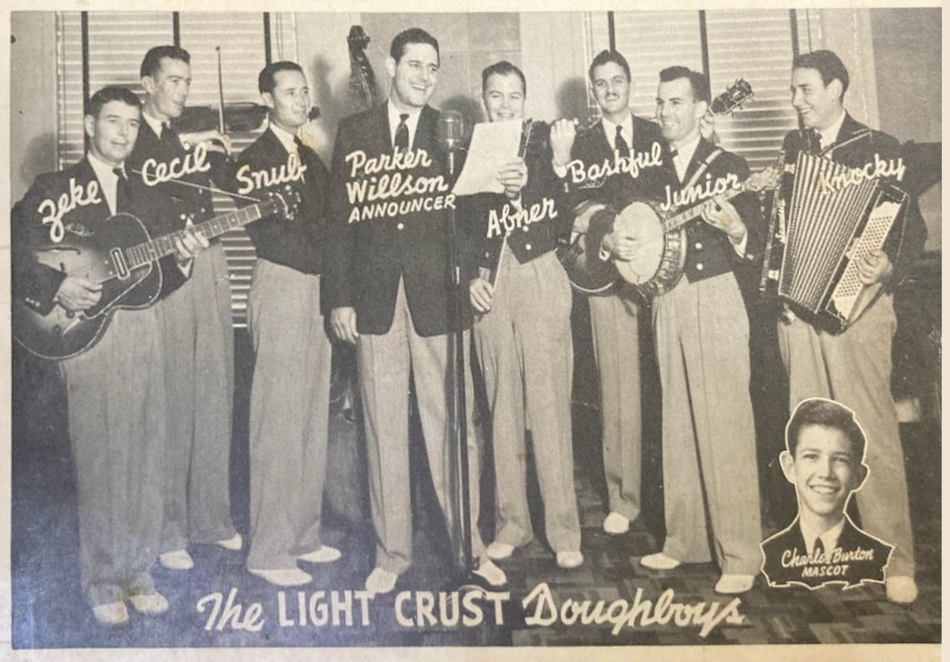

Aunt Jody was the beauty of the sisters, she was a musician too, she played what they called the “Hawaiian guitar” and the harmonica. She had a love affair with one of the Light Crust Doughboys, a famous country-and-western band that played on the radio. He was a protestant— and they were forbidden to marry. One day when the family was preparing to go back out into the field to work, Jody locked herself in the house, weeping. When they tried to get her out, she attacked one of them with a screwdriver. After that the family paid to have Jodi taken to Galveston for electro-shock treatments. She didn’t speak for seven years after that. She was never the same. When I knew her she was a shattered and nervous old woman who kept stray cats in cages because she was afraid they’d be captured and vivisected for medical science.

“I don’t believe in God,” she said, “Because of the all fire ants and the stickerburrs.”

Pulpit

Depth: 6

“The word ‘Texas’ is a certain doom for Czechoslovaks”

According to Sean M Kelly’s book Los Brazos de Dios, in 1860 the lower Brazos area to the south of the Fridel family farm was a majority Black population (55%) with a very small ethnic Mexican and Indigenous population [@grandinEndMythFrontier2019, 20]. I have less information about the populations of the river bottoms of the upper Brazos and Navasota. These areas were less desirable than the lower Brazos lands that were run as plantations, but they were an important foothold area for immigrants and some freed enslaved people after the Civil War. Henry Kurten, a German soldier, had purchased a Mexican land grant there in 1864 and created a pipeline for chain migration, where German immigrants could work his land and then establish farms of their own [@brownTexasStateHistorical]. During the time that Texas was a slave state, the Germans were seen as an oppositional culture– using a family labor system to work their land [@kelleyBrazosDiosPlantation2010, 46]. Although Rev. Bergmann, a Silesian who is eventually called a demon by the surviving Texas Moravians, wrings his hands in his letter to Europe and claims that the ‘unlucky’ enslaved people he saw still live better than the Czechs since Texas is a land of milk and honey— implying that Christians who object to chattel slavery still practiced in the United states should adjust to it.

As Kelley notes, networks rooted in German identity were vital, not only to migration itself but also to eventual land acquisition. Although the pattern in which older migrants employed newer ones sometimes provoked charges of exploitation, in most cases it worked. Over 77 percent of German farmers owned their own land in 1850, compared with 69 percent of Anglos. In Cat Spring, 71 percent of German households owned property in 1850, and more than 80 percent did so in 1860 (47).

When German chain migration slowed, Slavic laborers like the Fridels were brought over with the same promise of land. Lured by a letter from a Silesian minister published in a Moravian newspaper promising tracts of plentiful and cheap land, nearly half of the first boat of Czech immigrants died in the crossing or of yellow fever when they reached Texas (46). Once in Texas, Slavs were either considered a non-anglo other, responsible for spreading intemperance (awkwardly called “Bo-Dutchmen” by their Anglo accusers) or considered Anglo themselves, depending on whether it was convenient to count them as a bulwark against ethnic Mexicans [@barberHowIrishGermans2010]. Czech Texan communities retained their language and culture for a prolonged period of time due to the location of their homesteads and the maintenance of Czech-only schools and churches [@eckertovaCzechsTexasMoravian2011].

Chain migration was also responsible for the creation of a Czech-speaking enclave within the German settlements, which originated in 1851 when a letter from a Silesian Protestant minister named Ernst Bergmann reached Josef Lesikar in Landskroun on the Bohemia-Moravia border. The letter outlined transportation costs and provided enticing details on agriculture in Cat Spring, so Lesikar quickly organized a party of sixteen families. As it turned out, his wife prevailed upon him to abandon the plan, and he was lucky he did. Half of those who left Landskroun perished in squalid conditions on the Atlantic crossing. Lesikar, however, stayed in touch with a survivor and passed his letters on for publication in the Moravske Noviny, a regional newspaper. In 1853 he organized seventeen more families and left that October for Bremen, although not before obtaining from the local authorities a fraudulent medical exemption from military service for his son. Seven weeks later the party landed in Galveston, and fourteen days after that they arrived in Cat Spring, where they encountered remnants of the previous party of immigrants.

[@kelleyBrazosDiosPlantation2010]

The Czech Texan population was relatively homogeneous because it passed directly from the Moravian village to Farm Texas. Poverty drove the Moravians to Texas, the prospect of cheap land and trying to escape long-term military service. Nevertheless, they often hesitated to leave and they put it aside for many years until the letters of the evangelical priest Bergmann finally seduced them- flowery depictions of Texas county and quality soil, and classifieds published in Czech newspapers. (translation)

[@eckertovaCzechsTexasMoravian2011]

Pastor Bergman arrived in 1849 with a large group of German families in Cat Spring, from where he wrote home letters calling for others to emigrate. One of the Czechs, who fled from Texas to Iowa writes about him: “As far as the community of Texas is concerned, The Czechoslovaks are not suitable, they have a worse climate, in which our countryman cannot work and are often subject to pernicious yellow fever. I came from there last year and several Czech families told about the sad position of the local Czechs, which Mr. Bergmann, the tricky priest with his enticing letters, coaxed to follow him. They cursed him- that through him they were greatly reduced in wealth and health and many have died; the word ‘Texas’ is a certain doom for Czechoslovaks, just like Temešský Banát in Hungary ”(Ar USA 33/6, p. 81, archive of the Náprstek Museum in Prague). (translation)

[@eckertovaCzechsTexasMoravian2011]

- 1837 Valentine Fridel Sr. Born

- 1845 Annexation of Texas by the United States

- 1848 Serfdom Abolished in Bohemia

- 1847-1849 The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life published

- 1850 Rev. Bergmann’s letter published in Moravské Noviny, urging Moravians to migrate to Texas

- 1855 Tonkawa people forced onto reservation

- 1859 Edmund Husserl born in Moravia

- 1861 US Civil War begins, First permanent color photograph

- 1862 US Emancipation Proclamation

- 1865 US Civil War Ends

- June 19 1865 Juneteenth

- 1866 Battle of Hradec Králové

- 1870 Texas Restored to the Union

- 1872 Fridels immigrate, Valentine Fridel Sr and family immigrate to Texas from Moravia (Bremen->Havana->New Orleans->Galveston)

Port

Depth: 6

Valentine Fridel - born February 14, 1837 - died August

Valentine Fridel - born February 14, 1837 - died August

30 1916 at the age of 79 years.

He was

born in Moravia (CZECHOSLOVAKIA) and was buried at

Kurten in the family cemetery on the

family farm.

Veronica Johanna Kopecky

born January 13, 1844 - died December 29,

1916 at the age of 72 years.

She was

born in Poland MORAVIA and was buried at Kurten

beside Va l e n t i n e .

They were farmers in Moravia.

Valentine Sr. and Veronica

came to America in 1872 after the Civil War.

They landed in Galveston,

Little Valentine Jr. was 4 years old and John was 2. Peter was

born shortly after they arrived.

They lived at Komens Creek for two years in Rosa Prarilla Rd for

six years near Fayetteville, Texas, all in Fayette County near La Grange,

Texas.

Then they moved to Kurten, Texas in Brazos County ^IN 1882 and lived there

for the rest of their lives, on the farm.

Valentine was a farmer, but could do other types of work.

farmer, he broadcast planted his seeds. As I talked to the Fridels

on the farm,

they said he grew the largest turnips they had ever

seen and the sweetest English peas, too.

He grew peanuts and collard greens next to his hog pens, so he

could just reach over and pick them to feed his hogs. They were the

largest hogs anyone had ever seen in the area .

Veronica was a midwife who helped the doctor deliver babies.

When the doctor had too many to deliver, Veronica would go and deliver

the babies herself.

She never charged for her services.

Several

older people still living in the Kurten area were delivered by her.

She was highly praised and respected by all who knew her.

It is said that after a few drinks that Valentine Sr. sure

liked to fight . He was a respected man in the community.

After a

granddaughter would take him soup, he would reach way up high on a

pantry shelf and get her a handful of prunes. (HER REWARD)

Thanks to Bernadette, Mary, Frances, Frank and Josephine Fridel for making the family history possible

SOUR @S1329062894@

2 PAGE National Archives at St. Louis; St. Louis, Missouri; WWII Draft Registration Cards for Texas, 10/16/1940-03/31/1947; Record Group: Records of the Selective Service System, 147; Box: 502

1 SOUR @S1328948790@

2 DATA

3 TEXT Valentine J Fridel<br>Gender: Male<br&a

4 CONC mp;amp;gt;Birth: Circa 1865 - Czechoslovakia<br>Re

4 CONC sidence: 1930 - Precinct 3, Brazos, Texas, USA<br>

4 CONC Age: 65<br>Marital status: Married<br&a

4 CONC mp;amp;gt;Immigration: 1872<br>Race: White&amp

4 CONC ;lt;br>Language: English<br>Father&

4 CONC #039;s birth place: Czechoslovakia<br>Mother&#

4 CONC 039;s birth place: Czechoslovakia<br>Wife: Agat

4 CONC a M Fridel<br>Children: Annie T Fridel, Anton M Fr

4 CONC idel, Joe H Fridel, Mary K Fridel, Frank T Fridel, Josephine O Fridel&am

4 CONC p;amp;lt;br>Census: lt;a id='household'>&l

4 CONC t;/a>Household<br>Relation to head; Nam

4 CONC e; Age; Suggested alternatives<br>Head; &l

4 CONC t;a href="https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10134-263225402/val

4 CONC entine-j-fridel-in-1930-united-states-federal-census?s=1240722252"&a

4 CONC mp;gt;Valentine J Fridel</a>; 65; <br&a

4 CONC mp;amp;gt;Wife; <a href="https://www.myheritage.com/research/

4 CONC record-10134-263225403/agata-m-fridel-in-1930-united-states-federal-cens

4 CONC us?s=1240722252">Agata M Fridel</a>; 61

4 CONC ; <br>Daughter; <a href="https://www.my

4 CONC heritage.com/research/record-10134-263225404/annie-t-fridel-in-1930-unit

4 CONC ed-states-federal-census?s=1240722252">Annie T Fridel&amp

4 CONC ;lt;/a>; 36; <br>Son; <a hre

4 CONC f="https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10134-263225405/anton-m-fr

4 CONC idel-in-1930-united-states-federal-census?s=1240722252">Anto

4 CONC n M Fridel</a>; 34; <br>Son

4 CONC ; <a href="https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10134-2

4 CONC 63225406/joe-h-fridel-in-1930-united-states-federal-census?s=1240722252"

4 CONC >Joe H Fridel</a>; 30; <br&a

4 CONC mp;amp;gt;Daughter; <a href="https://www.myheritage.com/resea

4 CONC rch/record-10134-263225407/mary-k-fridel-in-1930-united-states-federal-c

4 CONC ensus?s=1240722252">Mary K Fridel</a>

4 CONC ; 28; <br>Son; <a href="https://www.myh

4 CONC eritage.com/research/record-10134-263225408/frank-t-fridel-in-1930-unite

4 CONC d-states-federal-census?s=1240722252">Frank T Fridel&

4 CONC lt;/a>; 22; <br>Daughter; <

4 CONC a href="https://www.myheritage.com/research/record-10134-263225409/josep

4 CONC hine-o-fridel-in-1930-united-states-federal-census?s=1240722252"&amp

4 CONC ;gt;Josephine O Fridel</a>; 20;

2 NOTE @N0310@

1 SOUR @S1328948777@

2 PAGE https://www.myheritage.com/person-1081878_75983311_75983311/valentine-fridel

2 DATA

3 TEXT Added by confirming a Smart Match

2 NOTE @N0312@

1 SOUR @S1328948787@

2 PAGE https://www.myheritage.com/person-1502282_450458181_450458181/valentine-j-sr-fridel

2 DATA

3 TEXT Added by confirming a Smart Match

2 NOTE @N0314@

1 SOUR @S1328948791@

2 PAGE Valentine J Friedel (Friedl) II

2 DATA

3 DATE 26 OCT 2021

3 TEXT Added by confirming a Smart Match

2 NOTE @N0316@

1 SOUR @S1328948776@

2 DATA

3 TEXT Valentine J Sr Fridel<br>Gender: Male<b

4 CONC r>Birth: Aug 8 1865 - Moravia, Czechoslovakia<br&a

4 CONC mp;amp;gt;Marriage: Spouse: Agatha M Lero - Oct 31 1892 - St Joseph&

4 CONC #039;s Chur, Bryan, Texas<br>Immigration: 1872&

4 CONC ;amp;lt;br>Immigration: 1872<br>Residen

4 CONC ce: 1910 - Justice Precinct 3, Robertson, Texas, United States&l

4 CONC t;br>Residence: 1920 - Justice Precinct 3, Brazos, Texas, Uni

4 CONC ted States<br>Death: Dec 27 1956<br&

4 CONC ;amp;gt;Parents: <a>Valentine Sr Fridel</a>

4 CONC , <a>Veronica Johanna Fridel (born Kopecky)</a&

4 CONC gt;<br>Wife: <a>Agatha M Fridel (bor

4 CONC n Lero)</a><br>Children: <a&a

4 CONC mp;gt;Lena Regmund (born Fridel)</a>, <a>Ann

4 CONC ie Fridel</a>, <a>Anton Fridel</a&

4 CONC ;gt;, <a>Bernadetta Fridel</a>, <a&am

4 CONC p;gt;Joe Fridel</a>, <a>Verna Eva Fridel&

4 CONC ;lt;/a>, <a>Victoria Fridel</a>, &

4 CONC ;lt;a>Mary Friedel</a>, <a>Frances Fr

4 CONC idel</a>, <a>Frank Fridel</a>

4 CONC , <a>Josephine Friedel</a>

2 NOTE @N0318@

1 SOUR @S1328948792@

2 PAGE https://www.myheritage.com/person-3511182_57865772_57865772/valentine-j-friedel-friedl-ii

2 DATA

3 TEXT Added by confirming a Smart Match

2 NOTE @N0320@

1 SOUR @S1328948793@

2 PAGE https://www.myheritage.com/person-2001287_135779482_135779482/valentine-j-fridel

2 DATA

Ossuary

Depth: 15

The Chamber of the Golden Cradle

Depth: 28

“The Golden Cradle,” appears in the mythologies of several Eurasian cultures as a coveted quest object. Sometimes, like the Grail, said to have been touched by Christ. The notion that Christ, traditionally described as being born in a manger, instead slept in a golden cradle is an inversion some might find suspicious. In earlier versions of the myth, the cradle was not merely an object but the child within it—Āltūn Bīshīk—a Moses-like figure whose lineage was meant to link the ruling dynasties of what is now Uzbekistan to the Central Asian Khanates.

In Crimea, variants of the Golden Cradle legend emphasize the cradle as a symbol of hope and continuity for various ethnic groups, and their connection and prophesied return to a homeland, each adapting the myth to affirm their historical presence and rights in the region. The Crimean Golden Cradle Myths have continued to evolve even in modern times, incorporating stories of Soviet and Nazi searches for mystical power objects and even engaging world leaders like Stalin, Hitler, and Putin as characters. These legends have been further embellished by popular media, claiming the cradle holds a key to humanity’s origins or a portal to other worlds. Notably, the Golden Cradle’s latest appearance in popular culture involved a symbolic gift to Vladimir Putin, hinting at its continuing role in symbolizing power and sovereignty over Crimea. This living myth, deeply intertwined with regional and global history, has spurred a tourist industry of would-be treasure hunters, searching the mountain caves of the Crimean region for the imagined artifact [@zherdievaGoldenCradleQuest2017].

‘Libussa prophesizes the glory of Prague’ (Max Švabinský,

1950)

‘Libussa prophesizes the glory of Prague’ (Max Švabinský,

1950)

In Jirásek’s Old Bohemian Tales, the Golden Cradle was used by the Czech prophetess Libuše. The cradle symbolized the legitimacy of the ruling dynasty that she would found with her husband Přemysl (a historical dynasty that claimed descent from mythological figures). On suffering a vision of a future filled with ruin and bloodshed because Libuše had surrendered rule to her husband, she sank the cradle, a wedding gift, to the depths of the Vltava river, prophesying that it would return when a just ruler of the Czech people was born. Like other stories involving quest objects, these myths have been used to evoke a shared national identity and a mythological background to accept a pre-ordained ruler. 9

Often Libuše would descend from her castle to the foot of the rock of Vysehrad, to her solitary bath, where Vltava had carved out its deepest pool. One day at this spot, as she looked into the flood of the water on the threshold of the bath, in the eddies of its dark depths she saw into the future, for at that instant the spirit of prophecy caught her up into ecstasy.

The currents flowed by, and with them glimmered in their sombre depths vision after vision. They came with the stream, and with the stream they passed, and as they receded they grew ever more black and threatening, ever more sorrowful, until the mind failed and the heart ached to see them.

Pale and trembling, Libuše bent her head above the river, and with horrified eyes followed the dreadful revelations of the waters.

In wonder and fear her maidens looked at their princess, as she peered into the river in agonised agitation, sobbing; and heavily then she spoke, in a voice strangled with grief ‘I see the blaze of fires, flames slash through the darkness of the waters. In the flames villages, castles, great buildings, and all dying-dying!’

‘And in the blaze of the fires I see bloody wars, war upon war. And such wars! Pale bodies, full of wounds and blood. Brother killing brother, and the stranger trampling on their necks. I see misery, humiliation, a terrible penalty for all.’

Two of her maidens brought to her the golden cradle of her firstborn. The soft light of consolation touched Libuše’s eyes and lit up her pale face. She kissed the cradle, and then plunged it into the bottomless depths of the pool, and bending above the water she said in a voice trembling with emotion:

‘Rest there in the deep, cradle of my son, until time shall call you back again!

You will not remain for ever in the dark depths of the waters, the night that is to cover your land will not be without end. A clear day will dawn, and happiness will again shine forth over my nation.’ ‘Cleansed by suffering, strengthened by love and labour it will rise erect in its might, and fulfil all its aspirations, and enter again upon glory.’

‘And then you will shine again through the dark waters, you will arise into the light of day, and the saviour of the land, foretold long ages before, shall rest in you, being still a child.’ [@jirásek1963legends]

Jirásek, in assembling the Staré pověsti české (Ancient Bohemian Tales), might have been influenced by a similar motive—to use the cradle as a nationalistic symbol, embodying the foundational myths of a nascent Czech identity. The Libuše myths themselves have gone through as many permutations and allegorical reversals of meaning as the pan-Eurasian tales of the Golden Cradle have.

In a moment that stirred outrage among ethnic Tatars, Russian President Vladimir Putin is presented with the sacramental object “Altyn Beshik” - a golden cradle, which is a symbol for the Crimean Tatars. [@vannekGoldenCradlePutin2015]

In a moment that stirred outrage among ethnic Tatars, Russian President Vladimir Putin is presented with the sacramental object “Altyn Beshik” - a golden cradle, which is a symbol for the Crimean Tatars. [@vannekGoldenCradlePutin2015]

Lake

title: “Subterranean lake” depth: 4 —

My family landed in Galveston, Texas in 1879, finally settling in Kurten in 1882 in a community that had already been a German/Slavic enclave for some time. I often wonder about those who lived on the land in Kurten before the Moravians and their farm. The town was founded in 1864, near the end of the Civil War , some time after Anglo settlers (under the leadership of Steven F. Austin) murdered and dispersed the native Karankawa people who had lived along the Brazos river (originally known as the Tokonohono). 10 There may have been Tonkawa or Nʉmʉnʉʉ people using the area at one time as well. 11

These areas were less desirable than the lower Brazos lands that were run as plantations, but they were an important foothold area for immigrants and some freed enslaved people after the civil war. Henry Kurten, a German soldier, had purchased a Mexican land grant there in 1864 and created a pipeline for chain migration, where German immigrants could work his land and then establish farms of their own [@TSHAKurtenTX]. During the time that Texas was a slave state, the Germans were seen as an oppositional culture– using a family labor system to work their land.

Networks rooted in German identity were vital, not only to the passage itself, but to the eventual acquisition of land. To be certain, the pattern in which older migrants employed newer ones brought occasional charges of exploitation, but in most cases it worked. Terry Jordan found that over 77 percent of German farmers owned their own land in 1850, compared with 69 percent of Anglos. In Cat Spring, 71 percent of German households owned property in 1850, and more than 80 percent did in 1860.

[@kelleyBrazosDiosPlantation2010]

When German chain migration slowed, Slav laborers like my family were brought over with the same promise of land. Lured by a letter from a Silesian minister published in a Moravian newspaper promising tracts of plentiful and cheap land, nearly half of the first boat of Czech immigrants died in the crossing or of yellow fever when they reached Texas [@kelleyBrazosDiosPlantation2010].

Pages

Libuše

Linked from: /rooms/cradle

Walter Benjamin’s allegory of the Angel of History—anchored in his idiosyncratic reading of Paul Klee’s painting “Angelus Novus”—reorients us toward time, or more precisely, toward material history. Benjamin imagined ‘progress’ as a growing pile of rubble pushing his witness backwards into the unknown, where once instead we might have imagined a Tower of Babel reaching ever skyward before toppling into sudden eschaton.

My ‘angel of history’ is the mythological Czech prophetess Libuše, a pagan witch who, in stories, foretells the founding of the city of Prague. In my allegory, Libuše exists in a vertical simultaneity of time, with the past below and the future above. Voices from the future call to her in the deep dungeon of the past and her voice echoes the message back, reflecting off the sedimentary strata of the walls of the pit. This is often the fantasy backdrop I use when genre elements are needed to make my game-like works fit into the history of games that they reference. Slavic mythology interests me not because of personal heritage, but because it reveals how different polities mobilized language, myth, and cultural symbols during a prolonged period of struggle—through kingdoms, empires, and nation-states—under immense internal and external pressures. At the heart of that struggle was a continual reimagining of who the community in the Czech lands was understood to be, shaped both from within and imposed from above, along with contests over who could lay claim to its cultural heritage and material wealth: fertile farmland and mineral resources that would help shape the fate of the world, including the a once productive mine that both filled the coffers of the first capitalist enterprises with silver and uranium that built the nuclear arsenal of the Soviet Union.

The Prophetess Libuše, Vitezlav Karel Masek 1893

The Prophetess Libuše, Vitezlav Karel Masek 1893

The name “Libuše” might have originated from an ancient mistranslation. Kosmas of Prague first mentioned her in the Chronica Boemorum in 1125, but his enumeration of the names of the Přemyslov family (Libuše’s lineage, mythical chieftains of an early Czech tribe) closely resembles what could be a Latin transcription of Old Slavic words intended to deter Frankish aggressors (Karbusický 2009). In this light, the prophetess herself is a construction of language, a glitch of translation.

In 1817, a forged medieval manuscript containing an apparently undiscovered Slavic epic poem attempted to place the name “Libuše” even further back in history than Kosmas’ text. This is not an isolated incident—myths of many cultures often insert themselves into history through forgery and strategic archival placements (Thomas 2010). In this case, details were added to the myth of power passing from Libuše to a man, suggesting that ancient Slavic culture had a democratic character before the adoption of Christianity and patriarchy. This was the planting of a myth meant to be used as a foundation for a Czech national culture, but was pronounced a forgery by the first president of the new Czechoslovak state, the progressive philosopher Tomáš Masaryk.

An opera about the prophetess by nineteenth century Czech composer Bedřich Smetana, dismissed by the critics of his time, was performed in the Prague national theater in 1939, under nazi occupation. separated from the incongruous, melancholy facets of the myth (such as a bloody war between the sexes brought on by Libuše’s ceding power to a husband), the unremarkable opera became a rousing ode to an oppressed independent nation, and was met with thunderous applause by its audience and promptly banned by the Nazi occupying force. In some versions of Libuše’s prophecy, she foresaw not just the building of Prague but predicted the mining of the Ore Mountains (Jirásek 1894). After speaking the locations of Silver, Gold, Lead and Tin lodes, Libuše goes on to warn of the foreign invaders who will covet the metals, “Beware, lest from the gifts of your own earth He should forge fetters to enslave you,” (Jirásek 1894). With each shift in power, rulers of the Czech lands altered Libuše’s prophecy, grappling for control of both the mines and history. The prophetess knows the future because she is compelled to utter the words of future writers. Her words sound not in the past, crowded with the unresponsive dead, but with us in the future. The prophecy could be an argument for primordial communism or the divine right of kings, for feminism or patriarchy. Allegory, as Benjamin laid out in his work on the Origin of German Tragic Drama, Ursprung des deutschen Trauerspiels, is unfixed from its referent. It is “the art of the fragment, the opposite of the symbol, which presupposes the value of ‘Nature’ preserving unchanging, complete identities and values” (Tambling 2010, 5). An allegory changes meaning to meet the moment. It does not require much or any rewriting to do this. The political context of each retelling is a light of a different color in which some details become significant and some become noise. That which is obvious and didactic can become camouflage for some concealed punctum. Walter Benjamin’s idea of jetztzeit—a “messianic” time opposed to the homogeneous, sequential time measured by clocks and calendars, punctuated by ruptures that open opportunities for change—finds a rough parallel in moments of technological history when new possibilities suddenly emerge. The introduction of affordable ‘personal’ computing disrupted traditional barriers to technology and power to some extent but also reinforced existing inequalities. Computers represent more than just tools; they symbolize progress, inequality, hope, oppression, and cultural shift— a symbol of the future now itself old enough to be patinated with layers of nostalgia and trauma. The narrative of ‘technological progress’ is mythologized, set aside from its material origins, as a game sidesteps the world in which it is inset with heterotopic rules.

Book

Linked from: /rooms/temple

In The Torah/Old Testament, genealogy is used to establish the lineage of important figures, such as Abraham, Moses, and David. The genealogies are often used to illustrate the fulfillment of prophecies or to establish a sense of divine mandate for certain characters.

Genealogy is a story, set in grammars that claim historicity and assert the universality of family structures that are anything but universal. They also create imagined communities out of groups of people with common ancestry who are, for all practical purposes, strangers. Akenson writes:

Biblical genealogies are artistic in nature by virtue of their being a massive metaphor. They account for human life, religious practices, and dynastic and geo-political events “through a metaphor of biological propagation.” Thus, world history necessarily becomes a form of family history. This is a metaphorical framework so strong that the biblical tales could not be told in any other way: if the stories jumped out of the framework of genealogical narrative they would not be biblical. It is as simple as that: the covenant between Yahweh and his people is between an imperious god and an imperial sperm bank. As Yahweh promises Abraham, “I will make thee exceeding fruitful, and I will make nations of thee and kings shall come out of thee” (Genesis 17:6). (2007, 292)

Genealogy is a very different mode of history writing than the work of historical geneticists, who create a picture of humanity’s history by investigating the genetic variation that exists within and between populations and how this variation changes over time. In some ways genealogy is like counting individual grains of sand in order to study a beach (and frequently losing count). Such an approach to history does reorient one to the vastness and interconnectedness of humanity, however. Moving through my family tree person-by-person inside my game experiment has also made me realize how little of my ancestry I have any knowledge of or affinity for. I also found in my research just how much of what I knew from family lore contradicted historical records, and inversely how much of the lived experiences of family members was left out of those records.

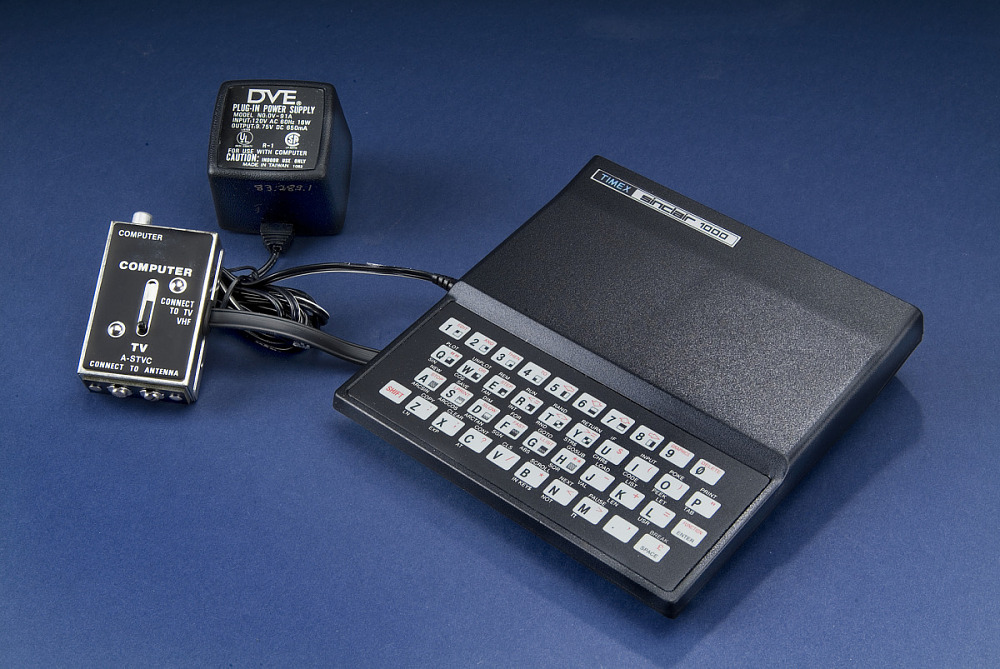

The Timex Sinclair 1000

Linked from: /rooms/first-chamber, /didaktik.html, /console.html

It was unusual that the Timex Sinclair 1000 ended up being my first computer. It was the American version of the Sinclair ZX81, developed by Sinclair Research in the UK and resold by the famous watch manufacturer in the States in 1981. Like the ZX Spectrum, it was compact and affordable, if underpowered and lacking color graphics. The Timex Sinclair 1000 featured a Z80 microprocessor, 2 KB of RAM (expandable to 16 KB), and a flat ‘membrane’ keyboard. It was not a popular computer in the US, although its low price kept it competitive. My mother had found one, not functioning but complete, in the trash at her job- she was a teacher in the embattled Head Start government subsidized preschool program where I was also a student. A school administrator had placed the computer, back in its box with manual and power adapter, in the trash. My mother gave it to me to play with and encouraged me to take it apart and look inside. I remember opening the computer’s plastic case with a screwdriver and finding that by clipping a broken ribbon connector I was able to get the computer functioning again. With the manual I was able to learn some programming in the embedded BASIC programming language. 12

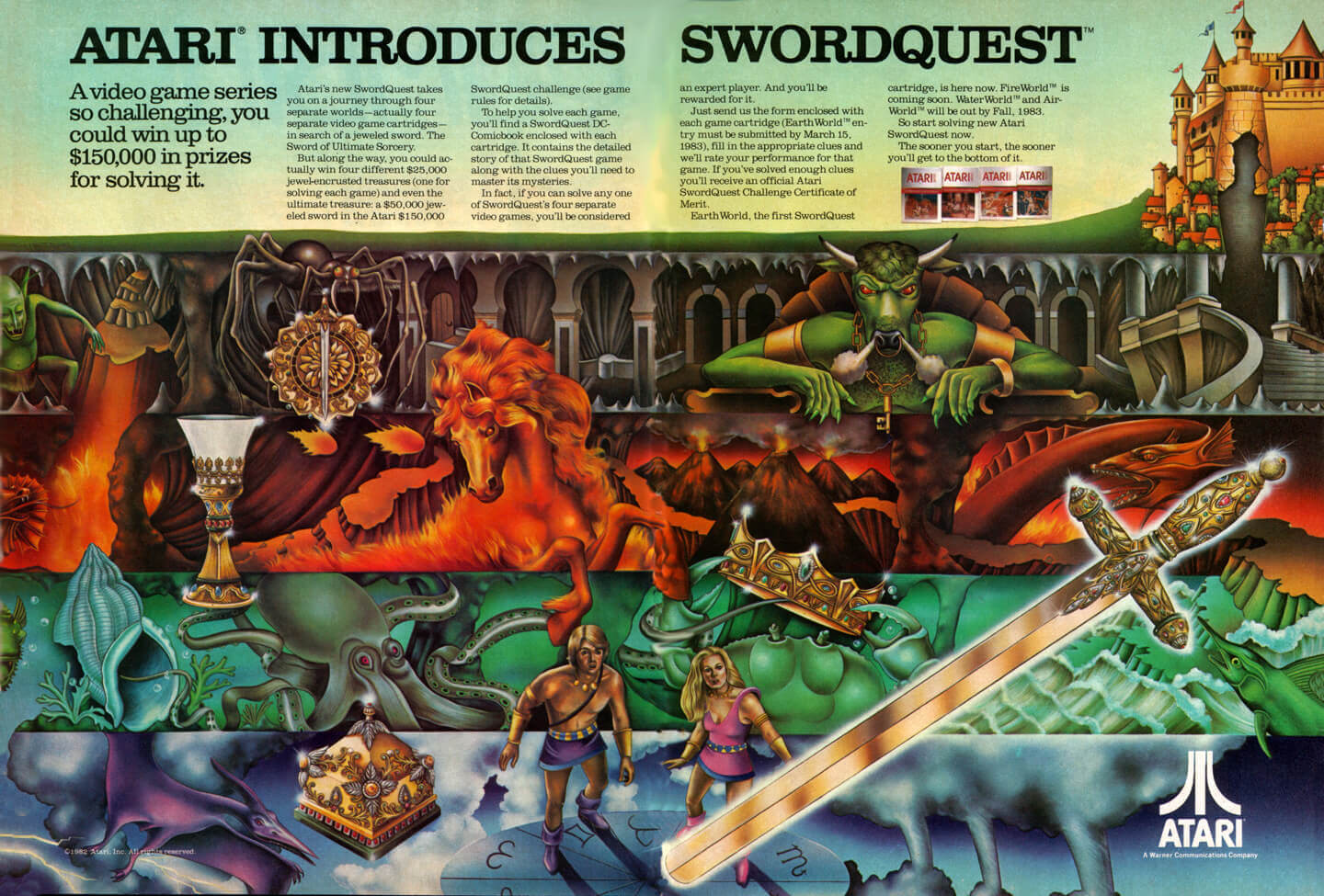

The Atari 2600

Linked from: /rooms/mud-room, /swordquest.html

The Atari 2600 (also known as Atari VCS, or “Video Computer System”), first released in 1977, was extremely popular and sold over 30 million units worldwide. The quality of the games made for Atari 2600 varied wildly– At its worst, it was a platform for inferior home-versions of popular arcade games. At its best, it was a space for experimenting with new kinds of play styles, working within hardware constraints, and engaging with a wide audience.

The Atari 2600 (also known as Atari VCS, or “Video Computer System”), first released in 1977, was extremely popular and sold over 30 million units worldwide. The quality of the games made for Atari 2600 varied wildly– At its worst, it was a platform for inferior home-versions of popular arcade games. At its best, it was a space for experimenting with new kinds of play styles, working within hardware constraints, and engaging with a wide audience.

By the early 1980s, the home video game industry in North America experienced a sharp decline, after the collapse of Atari. During this period, consumer electronics in the west shifted their design and marketing focus. Home computers were promoted as essential tools for education and home finance, rebranding computing devices as household information appliances. In Japan however, the game console market survived this downturn— Nintendo Inc’s “Family Computer” (Famicom) console was a surprise success following its 1983 release.

Only a thoughtless observer can deny that correspondences come into play between the world of modern technology and the archaic symbol-world of mythology. Of course, initially the technologically new seems nothing more than that. But in the very next childhood memory, its traits are already altered. Every childhood achieves something great and irreplaceable for humanity. By the interest it takes in technological phenomena, by the curiosity it displays before any sort of invention or machinery, every childhood binds the accomplishments of technology to the old worlds of symbol. There is nothing in the realm of nature that from the outset would be exempt from such a bond. Only, it takes form not in the aura of novelty but in the aura of the habitual. In memory, childhood, and dream.

[@@benjaminArcadesProject1999]

counter-genealogy

Linked from: kinship-citizenship.html

because Iceland was such a small society numerically, the penetration of Christianity throughout the culture occurred much more quickly than in those other nations. Secondly, Iceland had only been seriously settled from the last quarter of the ninth century, so the populace could (and did) maintain an accurate oral tradition of their family genealogies until, through the intervention of Christianity, they were recorded in written form. These genealogies existed coterminously with a sharp memory of general Nordic mythology as shared in large part with the other Norse cultures. Thus, thirdly, Iceland had an advantage in the cultural sweepstakes over the other Nordic nations in that it was relatively easy for it to throw up an educated elite who had mastered both reading and writing and who had lived in a society in which settler genealogy and sagas were organically intertwined in everyday life. Hence, it was Icelanders who become the premier paid remembrancers of the Norse aristocracy. The best of these was Snorri Sturluson who, among other things, produced a life of St Olaf of Norway and a biography of an Icelandic poet-warrior, and also a record of the kings of Norway and Sweden from the earliest times through the twelfth century. Some of this was puffery, but in fact it was also high art.1 Grasping Snorri’s personality is impossible for he comes from a world for which we have at present few cognate figures: a large and ambitious landholder in southern Iceland, a courtier to Norwegian royalty, a major political figure in his own country and, apparently, a fearsomely ill-tempered man whom you really did not wish to have sit at your table. Beyond that, he was a disciplined and erudite genius in prose, poetry, and poetics. Snorri’s monumental work, The Prose Edda, is (despite its title) in part about the theory of Nordic poetry and a thesaurus of figures of speech and of characters’ names, but that is not what is central to our present purpose. What counts here is that Snorri assembled in one package a coherent corpus of work, parallel to the Lebor Gabála in Irish mytho-genealogical writing but much smoother and more believable. He melds together a small bit of Christian piety with the largest collection of Norse mythology assembled in the Middle Ages, incorporates the genealogies of the ancient Norse gods, and joins these to sagas and genealogies that date from the settlement of Iceland and which were part of an oral tradition that was close enough in time to the actual events to be fundamentally factual, albeit not necessarily precise in every detail. […] Snorri was a Christian, or at least a shrewd enough courtier to bow his head before the Hebrew genealogies, however briefly.

[@akensonFamilyMormonsHow2007]

Snorri’s work conforms to Christian historiographic conventions, beginning with ritual homage to Genesis: “In the beginning Almighty God created heaven and earth and everything that goes with them and, last of all, two human beings, Adam and Eve, from whom have come families.” This feigned submission to biblical order allows Snorri to pivot almost immediately toward a rival lineage—a genealogical chain extending from human ancestors to Norse gods. Having invoked Adam and Eve to satisfy orthodoxy, he then “escapes smoothly and swiftly sideways,” constructing an alternative sacred history in which Odin, Thor, and their descendants populate a fully realized system of divine and human descent.

He explains that after Noah’s flood the population grew so large and their settlements so spread out that the great majority of humankind left off paying homage to Yahweh and boycotted all reference to him. Soon, they developed their own religion, one based upon the material world, but reflectively so: Snorri does not condemn it. Instead, he slides gracefully into telling us about the “Aesir,” Nordic gods who come from Asgard, an otherworld found vaguely in Asia and also, according to other Norse versions, where Valhalla and the palaces of various gods are located. Once he has a locale and a broad description of world geography defined, Snorri drops any pretence of Christian piety and gives us the real goods: god stories, genealogies, the works. Clearly this is an act of cultural resistance to the imperial might of the ancient Hebrew model as enforced through Christianity. That is interesting in itself, but I think Snorri is much cleverer than that: he is, I suspect, engaged in a massive subversion of the Hebrew-Christian genealogical program.

Snorri’s gesture, Akenson argues, is not mere defiance but “a massive subversion of the Hebrew-Christian genealogical program.” By using the structural logic of biblical genealogy—the very framework that legitimized Christian cosmology—Snorri turned it “inside out.” He appropriated its narrative machinery to enshrine pagan deities and local mythic histories as the ancestral foundation of Nordic civilization. This act of cultural counter-imperialism proved so effective that its logic survived far beyond its original context. Akenson demonstrates this by tracing how Snorri’s mythic genealogies, through centuries of repetition and transmission, found their way into the Mormon genealogical archives—the world’s largest repository of family lineage. There, figures like Odin, Frigg, and Skjold appear as historical ancestors, integrated seamlessly into lines of descent leading to medieval Norse rulers such as Somerled of Argyll. The Mormon database, designed to preserve the Hebrew-Christian genealogy of humankind, thus unwittingly perpetuates Snorri’s inverted version of it.

For Akenson, this strange convergence is the ultimate proof of Snorri’s success. His “seamless glove” of mythic genealogy still fits perfectly, centuries later—“turned inside out,” but perfectly shaped by his subversive hand.

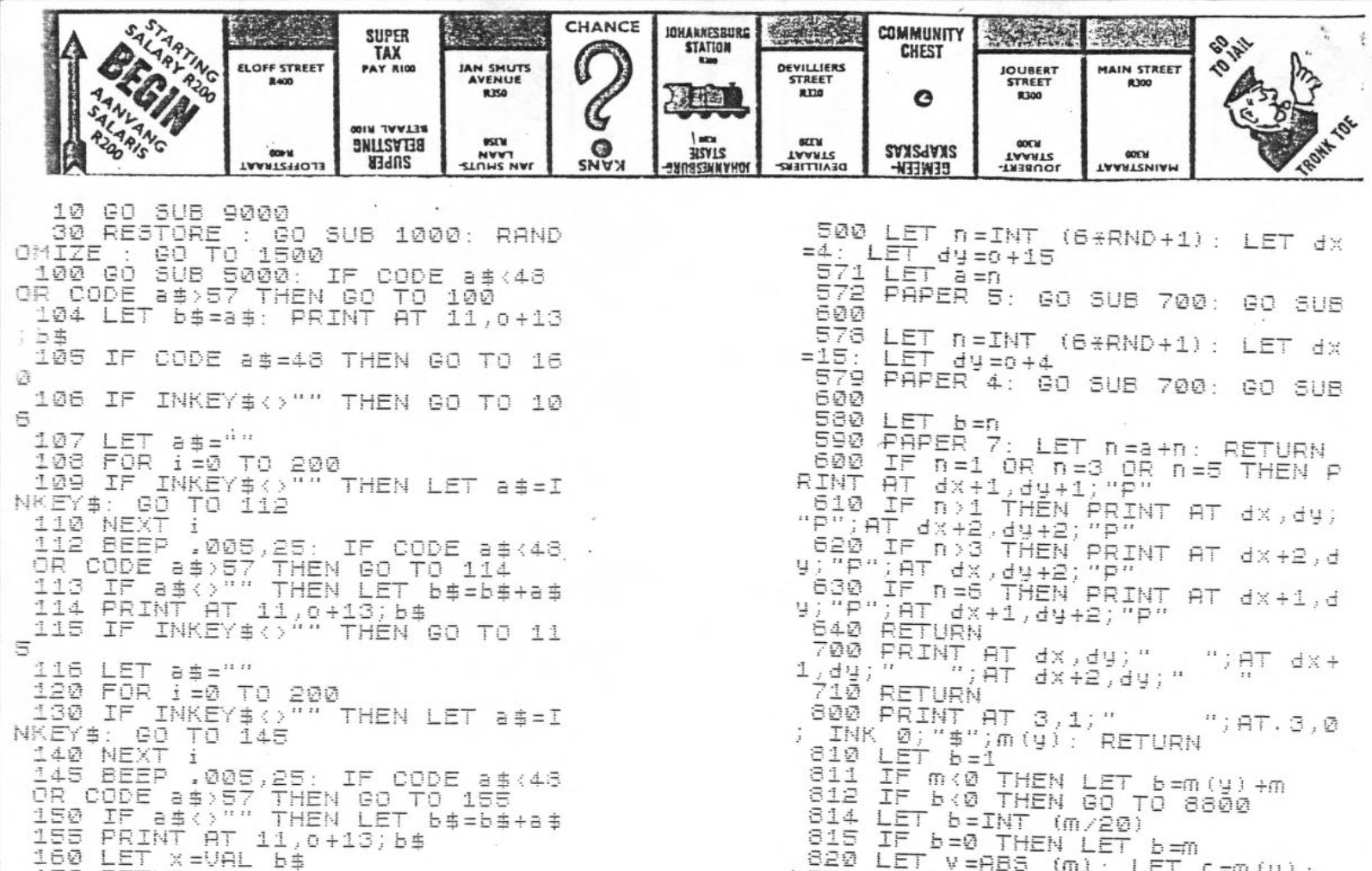

Didaktik Gama

Linked from: /computer.html

During the cold war, the CoCom (Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls) embargo denied the export of modern

technology, like CPU chips, to the Soviet bloc. In response, Eastern countries reverse-engineered chips and made their own copies. In places like Soviet satellite-state Czechoslovakia, hobbyist scenes sprang up, de-

spite the unavailability of parts and internal legal restrictions placed

on software sales. In 1987 Czech manufacturer of school supplies Didaktik Skalica, created a computer named Didaktik Gama – a clone of ZX Spectrum, extended with 8255 PIO and with RAM expanded to 80

kB.

During the cold war, the CoCom (Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls) embargo denied the export of modern

technology, like CPU chips, to the Soviet bloc. In response, Eastern countries reverse-engineered chips and made their own copies. In places like Soviet satellite-state Czechoslovakia, hobbyist scenes sprang up, de-

spite the unavailability of parts and internal legal restrictions placed

on software sales. In 1987 Czech manufacturer of school supplies Didaktik Skalica, created a computer named Didaktik Gama – a clone of ZX Spectrum, extended with 8255 PIO and with RAM expanded to 80

kB.

Homebrew Czechoslovak games from the time eluded censorship. Many were Textovka, a localized style of text-adventure that was unforgiving to play— stories that required typing in shorthanded verbs and cardinal directions to explore. Recently, I played through a collection of Slovak games translated as part of a project sponsored by the Slovak Design Museum. The more I played, what initially felt like poor game design resolved into a very specific flavor of dark humor about the futility and superficiality of choice, punishing arbitrary choices (sometimes the very first choice the player makes) with instant death. A few of the games also presented a distorted echo of western media and brand fetishism as seen through the eyes of their teenage programmers, imaging a world of abundance and freedom, in stark contrast to the actual experiences of many young Spectrum users in the UK. The difference in access to these devices themselves though, could not have been more glaring. In comparison to the flood of cheap computers in the UK, less than 2% of the Czechoslovak population owned a computing device during this period [@reed1988PRESTAVBA2021].

GEDCOM

Linked from: /underground-archive.html

The GEDCOM format, which stands for Genealogical Data Communication, is a plain-text specification developed to allow the exchange of genealogical data between different software programs. Rather than storing a tidy tree, GEDCOM files are more like sprawling lists of individual records—each person, event, or source is assigned a unique identifier. These IDs are then used to cross-reference relationships, weaving a complex web of pointers between parents, children, spouses, and associated documents.

This enrichment of what might otherwise be a simple tree diagram connects a genealogical record to sources like birth certificates, ship manifests, and census records. It’s a cited grammar of migrations, of deaths, associations with land, and of the transmission of culture, language, and wealth—a story far more intricate, and ultimately more revealing, than biological lineage, which is always suspect. GEDCOM is also notable in that it is a religious technology, developed by the Church of Latter Day Saints in the 1980’s.