My first Dungeon Mode experience was the Texas Instruments TI-99/4A version of the game Hunt The Wumpus. It was one of a handful of games included in a first-grade class meant to expose children to home computers, which were still a novelty at the time. This version of Wumpus was one of many derivations of the 1973 original Hunt the Wumpus–a text-based game made by Gregory Yob. The TI-99/4A was a slab of chromed plastic connected to a boxy CRT monitor. The blank white expanse of a new map on its screen was a dangerous territory to explore, one choice at a time. Each new cavern was represented as a circle, and the player as a stick figure within. One cave held a monster called the Wumpus. This expanse was understood from above but experienced from an occluded, perspectiveless, first-person view seen only in the mind’s eye. Carelessly pressing keys, I wandered through the Wumpus’s cave unaware, resulting in an animation of closing jaws and bleated notes from Chopin’s Piano Sonata No. 2 in B♭ minor —identifiable to a child only as the “you are dead” song. The screen had suddenly become my perspective as I had been eaten alive.

Jaws closed- the death screen of Hunt the Wumpus for the TI-994A Home Computer (Texas Instruments 1981)

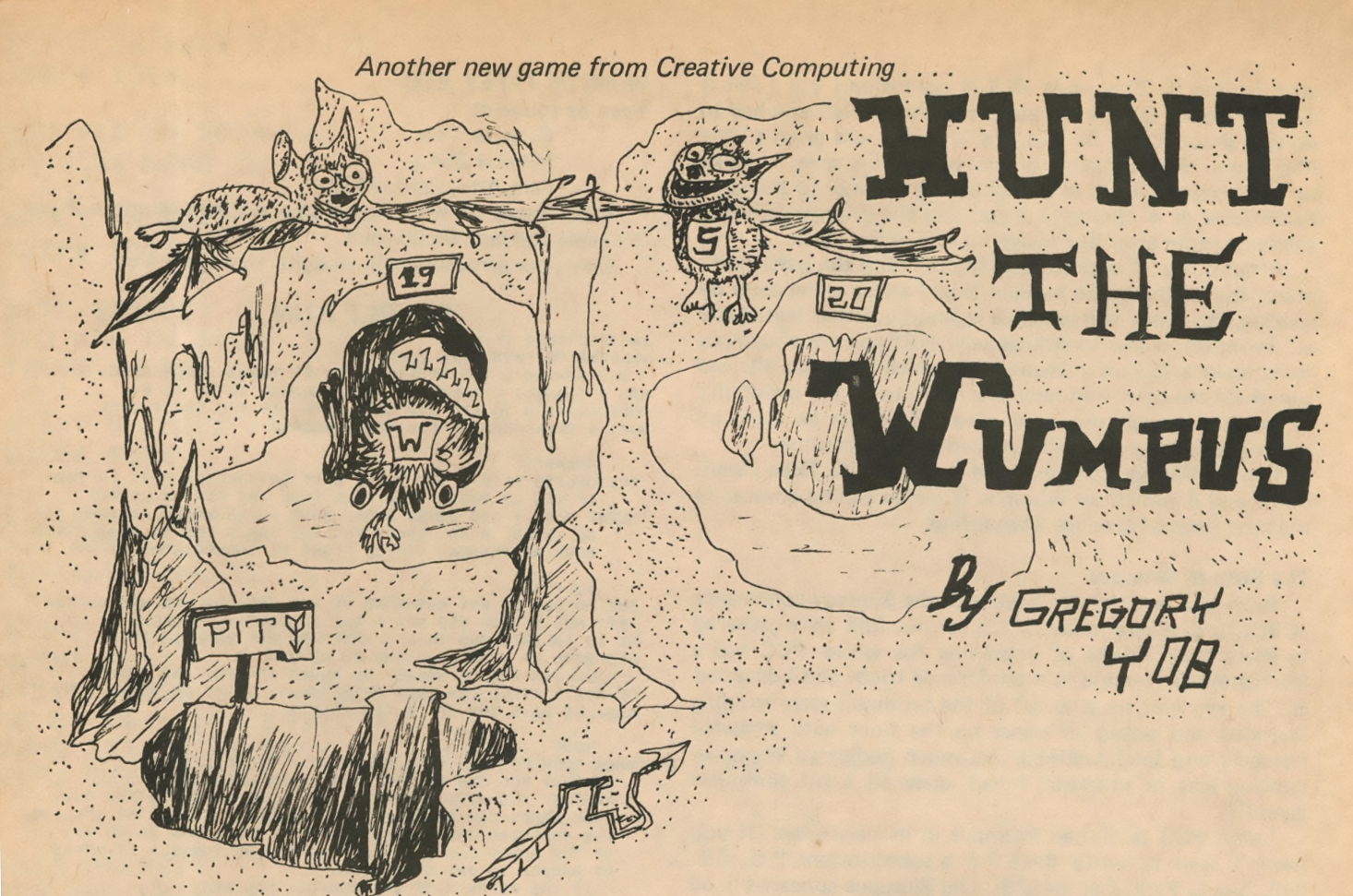

image Hunt the Wumpus for The Commodore PET (Gregory Yob 1978)

Stunned by my “fatal” experience with the Wumpus, I raised my hand to ask if I could use the restroom. Stepping out from the computer room in a still-unfamiliar school, I was immediately lost. In the many dreams inspired by that situation that have followed, the school has grown larger and larger. The hallways are branching out in an infinitely-generative pattern. What has carried over from this childhood experience into adulthood was a certainty that videogames exist as shadow extensions of the spaces in which they are played. The well-lit classroom where children were seated in rows and given commands by an adult was connected, as through a door, to a dark labyrinthine dungeon that was home to a ravenous minotaur.

In Grotto, we as players are descending through genealogy in the most literal way, to climb or descend a stairway leads the player back or forwards one generation, respectively. The orientation the words “up” and “down ” give us in the context of the dungeon are different from the lofty scholar’s, however. We imagine ourselves descending into darkness and becoming lost, not peering down from a safe height with ever-deepening sight. Grotto inherits as much of its design patterns from the seminal turn-based game Hunt the Wumpus, starting with a structure that seems settled—a family tree— then confusing that structure. A single room is viewed at a time as a map, but there are no consistent compass directions. Having entered the room of a child from the direction of a parent, a player finds that they are reoriented, and the inverse direction of their last move may not be the way back. To counter this spatial disorientation, doors are color coded to leave a breadcrumb trail back through the passages already traversed. Both roguelike games and Grotto have a sort of information architecture that is traversable, but can be conceived as spreading in infinite directions. The dungeons of roguelikes are procedurally generated, space-filling mazes that could extend as far as the game developer and the capacity of computer hardware allow. Grotto’s architecture (using family tree charts as its blueprint) flows from a biology that knows no origin point, and will theoretically continue to grow with each new generation. “Recession ad infinitum”(Roncato 2008) as an architectural feature can only exist in videogames and in a sort of imagined architecture that can never progress past sketches.